Resistant Starch

A unique type of starch that resists digestion, reaching the colon to feed beneficial bacteria and produce health-promoting short-chain fatty acids.

Food Sources

Naturally found in these foods:

Key Benefits

- Increases butyrate production

- Supports gut barrier integrity

- May improve insulin sensitivity

- Promotes beneficial bacteria growth

- Supports weight management

Bacteria This Prebiotic Feeds

This prebiotic selectively nourishes these beneficial microorganisms:

Overview

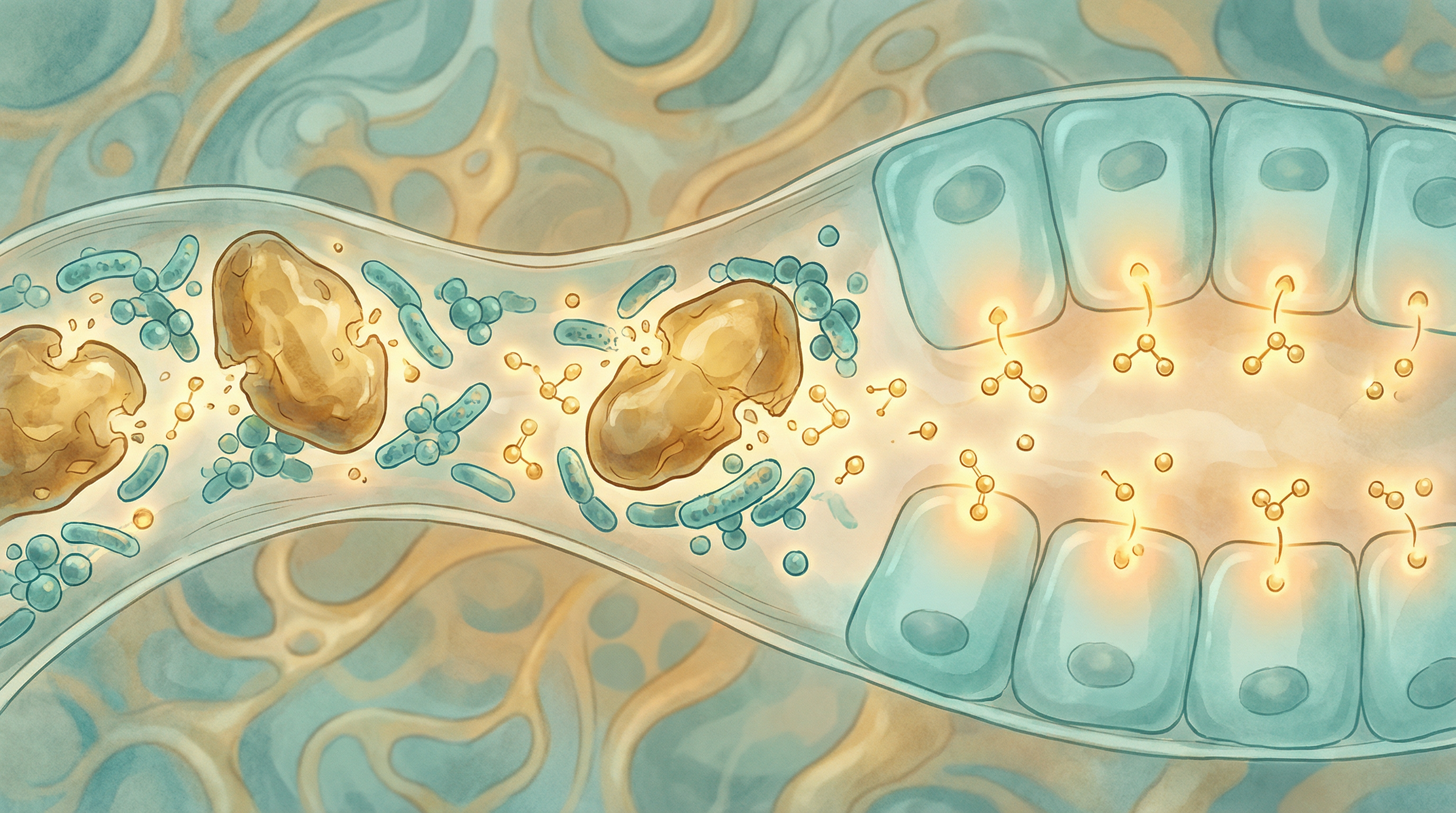

Resistant starch (RS) is a unique form of starch that "resists" digestion in the small intestine, passing intact to the large intestine where it becomes a fermentable substrate for beneficial gut bacteria[2]. Unlike regular starch, which is rapidly broken down to glucose and absorbed, resistant starch behaves more like dietary fiber, providing significant prebiotic benefits and producing health-promoting metabolites through bacterial fermentation.

Types of Resistant Starch

Resistant starch is classified into four main types based on structure and origin[1]:

RS1 - Physically Inaccessible

Found in whole grains and seeds where the starch is protected within intact cell walls. Examples include whole grain breads and legumes.

RS2 - Native Granular Starch

Found in raw, uncooked starchy foods with high amylose content. The tightly packed crystalline structure resists enzymatic attack.

- Sources: Raw potatoes, green bananas, high-amylose corn

RS3 - Retrograded Starch

Forms when certain starchy foods are cooked and then cooled. The amylose and amylopectin chains realign during cooling, creating resistant crystalline structures.

- Sources: Cooked and cooled potatoes, rice, pasta

RS4 - Chemically Modified

Industrially produced through chemical cross-linking or substitution to enhance resistance to digestion.

Mechanism of Action

The prebiotic effects of resistant starch involve a complex interplay between the substrate, specific microbial communities, and the host[1]:

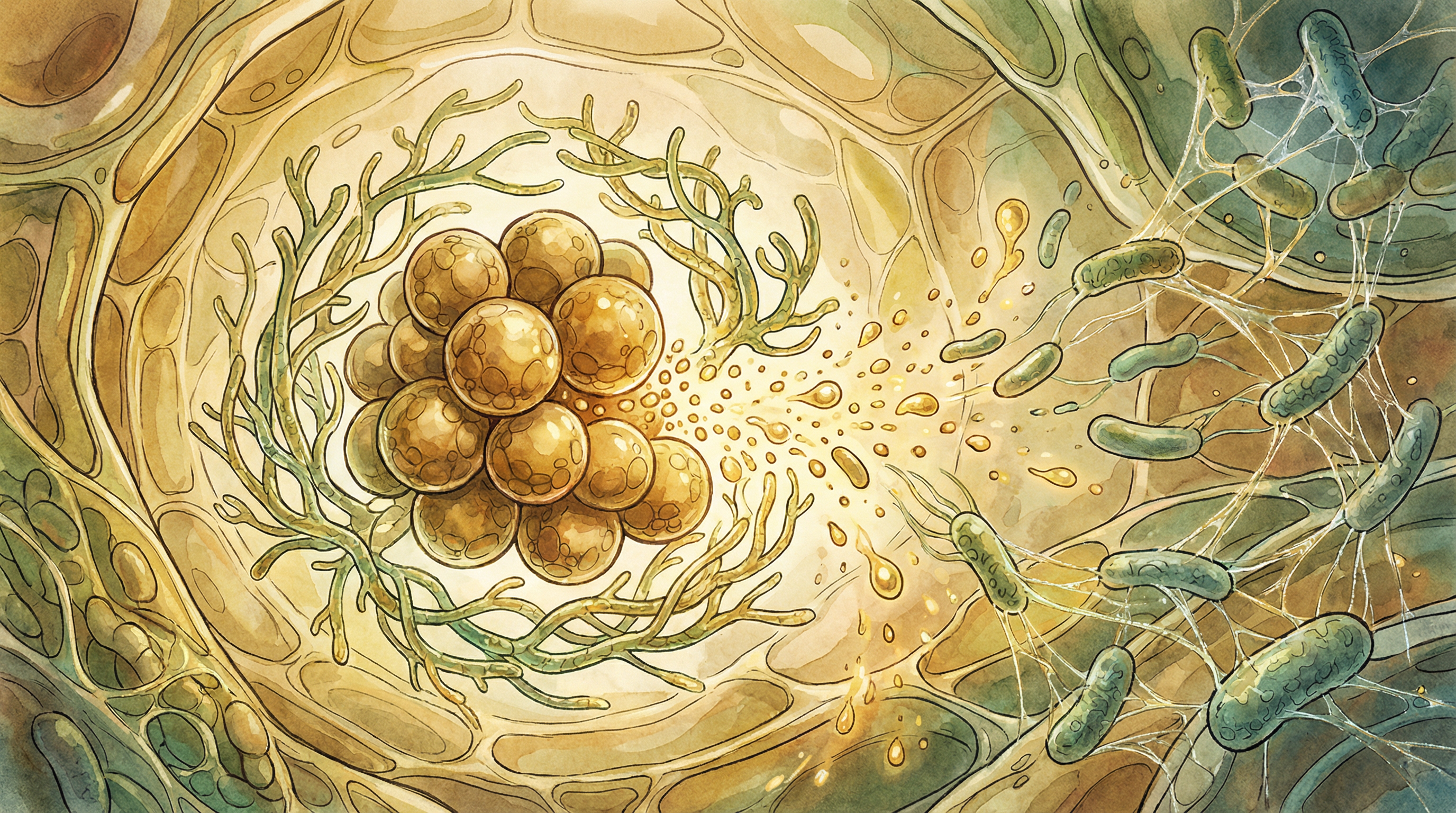

Primary Fermentation

Ruminococcus bromii has been identified as a "keystone species" for resistant starch degradation in the human colon[3]. This bacterium possesses specialized enzyme systems that initiate RS breakdown, making the degradation products available to other bacterial species.

Cross-Feeding Networks

The initial degradation products support the growth of secondary fermenters:

- Bifidobacterium species: Utilize oligosaccharides released from RS

- Bacteroides species: Participate in complex carbohydrate breakdown

- Butyrate producers: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium rectale convert fermentation products to butyrate

SCFA Production

Resistant starch fermentation produces significant amounts of short-chain fatty acids:

- Butyrate: The primary SCFA from RS fermentation, serving as the main energy source for colonocytes

- Acetate: The most abundant SCFA, with systemic metabolic effects

- Propionate: Influences hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Clinical studies have demonstrated that resistant starch consumption leads to reproducible shifts in gut microbiome composition[4]:

Consistently Observed Changes

- Increased Ruminococcus bromii abundance

- Enhanced populations of Bifidobacterium species

- Greater abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria

- Shifts in Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios

Type-Specific Effects

Different RS types may preferentially foster different microbial responses. RS2 (from high-amylose maize) and RS4 (chemically modified) have been shown to have differential effects on fecal microbiota composition, with RS4 showing more pronounced increases in certain Bacteroidetes members.

Duration and Adaptation

The gut microbiota shows adaptive responses to consistent RS intake. Initial introduction may cause rapid shifts, followed by stabilization. Long-term RS consumption appears to promote a more resilient and diverse microbiome[1].

Health Benefits

Gut Health

Resistant starch supports gut health through multiple mechanisms:

- Butyrate production: Supports colonocyte health and gut barrier integrity

- pH reduction: SCFA production lowers colonic pH, creating an environment unfavorable for pathogens

- Mucus production: Stimulates protective mucin secretion

- Anti-inflammatory effects: Butyrate inhibits NF-κB pathway and pro-inflammatory cytokines

Metabolic Health

Clinical evidence supports RS's role in metabolic regulation[5]:

- Improved insulin sensitivity: Demonstrated in both healthy individuals and those with insulin resistance

- Blood glucose control: Reduced postprandial glucose and insulin responses

- Lipid metabolism: Potential benefits for cholesterol and triglyceride levels

- Appetite regulation: Enhanced satiety through gut hormone modulation (GLP-1, PYY)

Weight Management

Resistant starch may support weight management through[6]:

- Lower caloric availability compared to digestible starch

- Increased satiety signaling

- Enhanced fat oxidation

- Improved metabolic rate through increased thermogenesis

Dosage and Sources

Recommended Intake

The recommended daily intake of resistant starch is 15-30g[1]. Most Western diets provide only 3-8g daily, well below optimal levels.

Dietary Sources

| Food Source | RS Type | RS Content (g/100g) |

|---|---|---|

| Green bananas | RS2 | 8-12 |

| Raw potato starch | RS2 | 65-75 |

| Cooked & cooled potatoes | RS3 | 3-5 |

| Cooked & cooled rice | RS3 | 2-4 |

| Legumes (cooked) | RS1/RS3 | 4-10 |

| High-amylose corn | RS2 | 25-40 |

| Oats (raw) | RS2 | 7-9 |

Enhancing RS Content

Simple cooking strategies can increase resistant starch[2]:

- Cook and cool starchy foods before eating

- Refrigerate cooked rice and potatoes overnight

- Multiple heating/cooling cycles may further increase RS content

- Adding fat during cooking may enhance RS3 formation

Practical Recommendations

Gradual Introduction

As with other fermentable fibers:

- Start with 5-10g daily

- Increase by 5g per week

- Target 15-30g daily over several weeks

- Allow gut microbiota time to adapt

Combining Sources

For optimal effects, include multiple RS types:

- RS2 sources (green bananas, raw potato starch) for rapid effects

- RS3 sources (cooked/cooled starches) for sustained fermentation

- Legumes for combined RS1 and RS3 benefits

Timing

Resistant starch can be consumed throughout the day:

- Morning: Raw oats, green banana in smoothies

- Lunch/Dinner: Cooked and cooled potatoes, rice, or pasta

- Snacks: Legume-based foods

Safety and Tolerability

Resistant starch is generally well-tolerated[1]. Potential side effects from rapid introduction include:

- Increased flatulence

- Bloating

- Changes in bowel habits

These effects typically diminish within 2-4 weeks of consistent intake as the microbiome adapts. Individuals with IBS or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) should introduce RS cautiously.

Summary

Resistant starch represents a powerful prebiotic with unique benefits for gut health and metabolic function. Its ability to selectively feed keystone species like Ruminococcus bromii while promoting butyrate production makes it distinct from other prebiotic fibers. The practical accessibility of RS through simple cooking and cooling techniques, combined with its metabolic benefits, positions it as a valuable dietary component for supporting gut microbiome health and overall metabolic wellness.

Dosage Guidelines

Recommended Dosage

15-30g daily

Start with a lower dose and gradually increase to minimize digestive discomfort. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized recommendations.

References

- Chen Z, Liang N, Zhang H, et al.. Resistant starch and the gut microbiome: Exploring beneficial interactions and dietary impacts. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;21:101118. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101118

- Birt DF, Boylston T, Hendrich S, et al.. Resistant starch: promise for improving human health. Advances in Nutrition. 2013;4(6):587-601. doi:10.3945/an.113.004325

- Ze X, Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. Ruminococcus bromii is a keystone species for the degradation of resistant starch in the human colon. The ISME Journal. 2012;6(8):1535-1543. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.4

- Martínez I, Kim J, Duffy PR, et al.. Resistant starches types 2 and 4 have differential effects on the composition of the fecal microbiota in human subjects. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15046. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015046

- Robertson MD, Bickerton AS, Dennis AL, et al.. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(3):559-567. doi:10.1093/ajcn.82.3.559

- Keenan MJ, Zhou J, Hegsted M, et al.. Role of resistant starch in improving gut health, adiposity, and insulin resistance. Advances in Nutrition. 2015;6(2):198-205. doi:10.3945/an.114.007419