IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease)

Explore the connection between gut microbiome imbalances and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, and discover evidence-based approaches for managing symptoms through microbiome optimization.

Common Symptoms

Microbiome Imbalances

Research has identified the following microbiome patterns commonly associated with this condition:

- Reduced microbial diversity

- Decreased Firmicutes

- Increased Proteobacteria

- Reduced butyrate-producing bacteria

Understanding Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Microbiome Connection

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a group of chronic inflammatory conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract. The two main forms of IBD are Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. While they share some similarities, they also have distinct characteristics:[1]

Crohn's Disease

- Can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus

- Inflammation extends through all layers of the bowel wall (transmural)

- Characterized by "skip lesions" (affected areas interspersed with healthy tissue)

- Common complications include strictures, fistulas, and abscesses

Ulcerative Colitis

- Limited to the colon and rectum

- Inflammation affects only the innermost lining of the colon (mucosa)

- Continuous inflammation without skip lesions

- Characterized by ulcers in the colon lining

IBD is considered an immune-mediated condition, where the immune system inappropriately attacks the digestive tract, leading to chronic inflammation. While the exact cause remains unclear, research increasingly points to a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, immune dysfunction, and gut microbiome alterations.

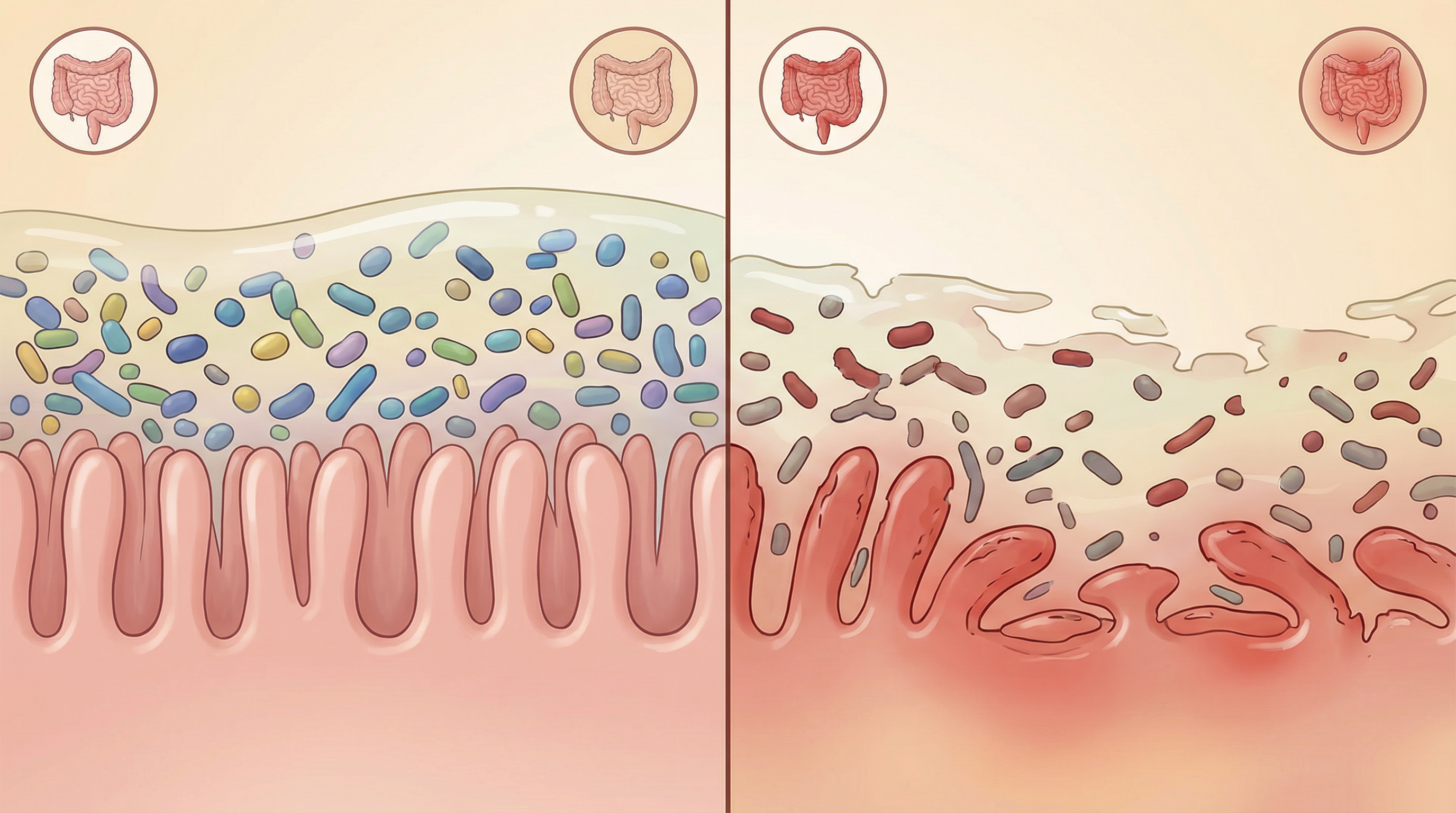

The Microbiome Disruption in IBD

Numerous studies have documented significant differences in the gut microbiome of IBD patients compared to healthy individuals:[1]

Reduced Microbial Diversity

- Lower overall species richness and diversity

- Less stable microbial communities

- Reduced resilience to perturbations

Taxonomic Shifts

- Decreased Firmicutes: Particularly butyrate-producing bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii[2]

- Increased Proteobacteria: Including potentially pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. An axis defined by increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Veillonellaceae, and Fusobacteriaceae correlates strongly with Crohn's disease status.[3]

- Altered Bacteroidetes: Changes in specific Bacteroides species, with decreased abundance in Bacteroidales characteristic of IBD

- Reduced Clostridia: Particularly clostridial clusters IV and XIVa, including Erysipelotrichales

Functional Changes

Comprehensive multi-omics analysis reveals functional dysbiosis in the gut microbiome during inflammatory bowel disease activity, with distinct microbial ecosystems in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.[4]

- Decreased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

- Altered bile acid metabolism

- Increased production of hydrogen sulfide

- Enhanced mucus degradation

- Increased bacterial adherence to intestinal epithelium

Spatial Disruptions

- Altered mucus-associated microbiota

- Bacterial invasion into crypts and epithelium

- Changes in bacterial biofilm formation

Mechanisms Linking Microbiome to IBD Pathogenesis

Several mechanisms connect gut microbiome alterations to IBD development and progression:

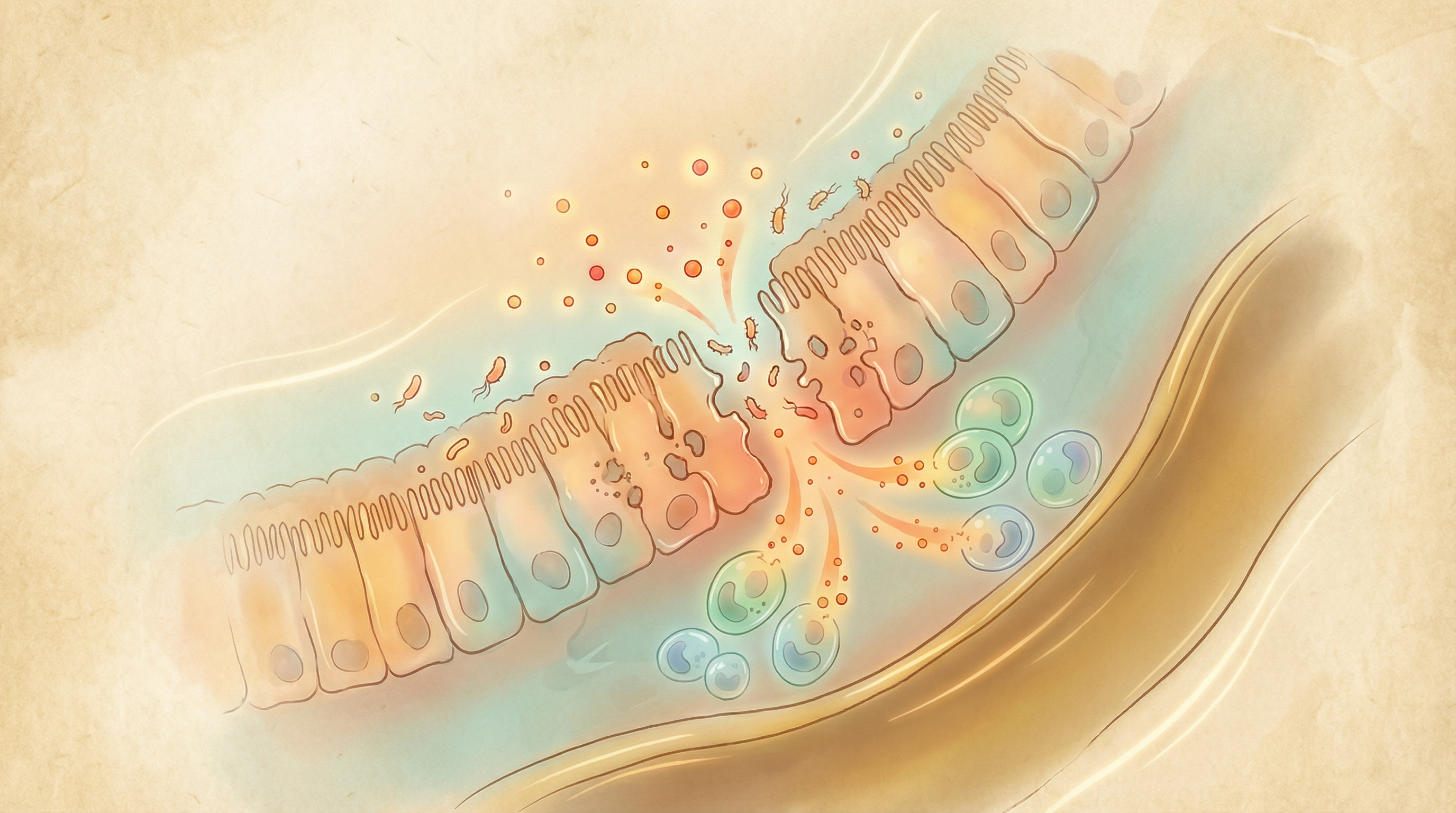

Barrier Dysfunction

The intestinal epithelium forms a critical barrier between gut contents and the body. In IBD:

- Reduced mucus production and integrity

- Compromised tight junctions between epithelial cells

- Increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut")

- Enhanced bacterial translocation

Immune Dysregulation

The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in immune system development and regulation:

- Reduced regulatory T cells (Tregs) that normally suppress inflammation

- Increased pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (Th17) cells

- Altered balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines

- Inappropriate activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)

Metabolic Consequences

Microbial metabolites significantly influence intestinal health:[2]

- Reduced SCFAs: Particularly butyrate, which fuels colonocytes and has anti-inflammatory properties

- Altered tryptophan metabolism: Affecting production of protective indoles

- Increased sulfide production: Potentially damaging to colonocytes

- Disrupted bile acid transformation: Affecting signaling and microbial composition

Key Microorganisms in IBD

Several specific microorganisms have been implicated in IBD pathogenesis or protection:

Protective Species

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

This beneficial bacterium:[2]

- Is typically depleted in IBD, especially Crohn's disease

- Produces butyrate and other anti-inflammatory compounds

- Strengthens the intestinal barrier

- Correlates with longer remission periods

Akkermansia muciniphila

This mucin-degrading bacterium:

- Helps maintain mucus layer integrity

- Enhances intestinal barrier function

- Is often reduced in IBD patients

Roseburia species

These butyrate-producing bacteria:

- Support colonocyte health

- Have anti-inflammatory properties

- Are frequently depleted in active IBD

Potentially Harmful Species

Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC)

These specialized E. coli strains:

- Can adhere to and invade intestinal epithelial cells

- Are found at higher rates in ileal Crohn's disease

- Persist within macrophages and induce inflammation

Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis

This Bacteroides strain:

- Produces a toxin that can damage the epithelium

- Induces colitis in animal models

- Is found at higher rates in some IBD patients

Fusobacterium nucleatum

This oral bacterium:

- Can invade intestinal epithelial cells

- Induces inflammatory cytokine production

- Is enriched in some IBD patients

Microbiome-Based Approaches for IBD Management

While conventional IBD treatments focus on suppressing inflammation and immune responses, microbiome-based approaches aim to restore a healthier gut ecosystem:[5]

Probiotics

Specific probiotic strains and combinations show promise for IBD management:

For Ulcerative Colitis

- VSL#3 (now marketed as Visbiome): A high-potency, 8-strain probiotic mixture[6]

- Evidence Level: Strong for maintaining remission, moderate for inducing remission

- Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: A non-pathogenic E. coli strain

- Evidence Level: Moderate for maintaining remission

For Crohn's Disease

- Saccharomyces boulardii: A beneficial yeast

- Evidence Level: Preliminary to moderate for maintaining remission

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: In combination with conventional therapy

- Evidence Level: Preliminary

Prebiotics

Non-digestible food components that selectively feed beneficial bacteria:

- Inulin-type fructans: May improve gut barrier function

- Galactooligosaccharides (GOS): Can increase bifidobacteria

- Resistant starch: Enhances butyrate production

Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

Synbiotics

Combinations of probiotics and prebiotics:

- May provide more comprehensive benefits than either component alone

- Show promise for reducing inflammation markers

Evidence Level: Preliminary

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Transfer of fecal material from healthy donors:[7]

- Shows variable results in IBD

- More promising for ulcerative colitis than Crohn's disease

- A 2023 meta-analysis demonstrated that FMT significantly improves both clinical remission and endoscopic remission rates in ulcerative colitis compared to control groups[8]

- Factors affecting success include donor selection, preparation methods, and recipient characteristics

Evidence Level: Moderate for ulcerative colitis, preliminary for Crohn's disease

Dietary Approaches

Specific dietary patterns can beneficially modulate the gut microbiome and reduce inflammation:[9]

Mediterranean Diet

Rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, and fish:

- Increases microbial diversity

- Enhances SCFA production

- Reduces inflammatory markers

Evidence Level: Moderate

Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD)

Eliminates complex carbohydrates and refined sugars:

- Based on the premise that undigested carbohydrates feed harmful bacteria

- Some clinical evidence for symptom improvement

- May help maintain remission in some patients

Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED)

Structured diet that excludes animal fats, milk proteins, and specific carbohydrates:

- Designed to reduce exposure to dietary components that may disrupt the microbiome

- Clinical trials show promise for inducing remission

Evidence Level: Moderate

Low FODMAP Diet

Restricts fermentable carbohydrates:

- May help manage symptoms, particularly in IBD patients with IBS-like symptoms

- Not recommended long-term due to potential negative effects on beneficial bacteria

Evidence Level: Moderate for symptom management, not recommended for long-term use

Clinical Evidence and Research Highlights

Recent studies have provided important insights into microbiome-based approaches for IBD:

A landmark randomized controlled trial in The Lancet found that intensive multidonor FMT induced remission in 27% of ulcerative colitis patients compared to 8% with placebo, with responders showing increased microbial diversity.[7]

Research in PNAS demonstrated that Faecalibacterium prausnitzii has potent anti-inflammatory properties and is consistently depleted in Crohn's disease patients.[2]

A study in Cell Host & Microbe showed that diet, antibiotics, and inflammation independently alter the pediatric Crohn's disease microbiome, with exclusive enteral nutrition partially restoring a healthy microbiome.[9]

Personalized Approaches to IBD Management

The future of IBD management lies in personalized approaches that consider individual microbiome profiles, genetic factors, and disease characteristics:

- Microbiome Testing: Analyzing a patient's gut microbiome composition to identify specific imbalances

- Targeted Interventions: Selecting probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary approaches based on individual needs

- Combination Strategies: Integrating microbiome-based approaches with conventional treatments

- Monitoring and Adjustment: Regular reassessment of microbiome composition and treatment response

This personalized approach recognizes that IBD is a heterogeneous condition, and what works for one patient may not work for another. By tailoring interventions to individual microbiome profiles, clinicians may be able to achieve better outcomes and improve quality of life for IBD patients.

Research Summary

Research has established significant alterations in the gut microbiome of IBD patients, with reduced diversity and beneficial bacteria alongside increased pathobionts. Studies show that microbiome-based interventions, including specific probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary modifications, can help manage symptoms and potentially extend remission periods in some patients.

References

- Ni J, Wu GD, Albenberg L, Tomov VT.. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation?. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;14(10):573-584. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.88 ↩

- Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al.. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(43):16731-16736. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804812105 ↩

- Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, et al.. The Treatment-Naive Microbiome in New-Onset Crohn's Disease. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15(3):382-392. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005 ↩

- Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al.. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569(7758):655-662. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9 ↩

- Shen ZH, Zhu CX, Quan YS, et al.. Relationship between intestinal microbiota and ulcerative colitis: Mechanisms and clinical application of probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;24(1):5-14. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.5 ↩

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al.. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(10):2218-2227. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.218 ↩

- Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al.. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1218-1228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30182-4 ↩

- Feng J, Chen Y, Liu Y, et al.. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2023;13:14494. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-41182-6 ↩

- Lewis JD, Chen EZ, Baldassano RN, et al.. Inflammation, antibiotics, and diet as environmental stressors of the gut microbiome in pediatric Crohn's disease. Cell Host & Microbe. 2017;22(2):247-259. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.011 ↩