Fructooligosaccharides (FOS)

Short-chain prebiotics that selectively feed beneficial Bifidobacterium species and support digestive health.

Food Sources

Naturally found in these foods:

Key Benefits

- Promotes Bifidobacterium growth

- Supports immune function

- Improves mineral absorption

- May reduce intestinal pathogens

- Enhances SCFA production

Bacteria This Prebiotic Feeds

This prebiotic selectively nourishes these beneficial microorganisms:

Overview

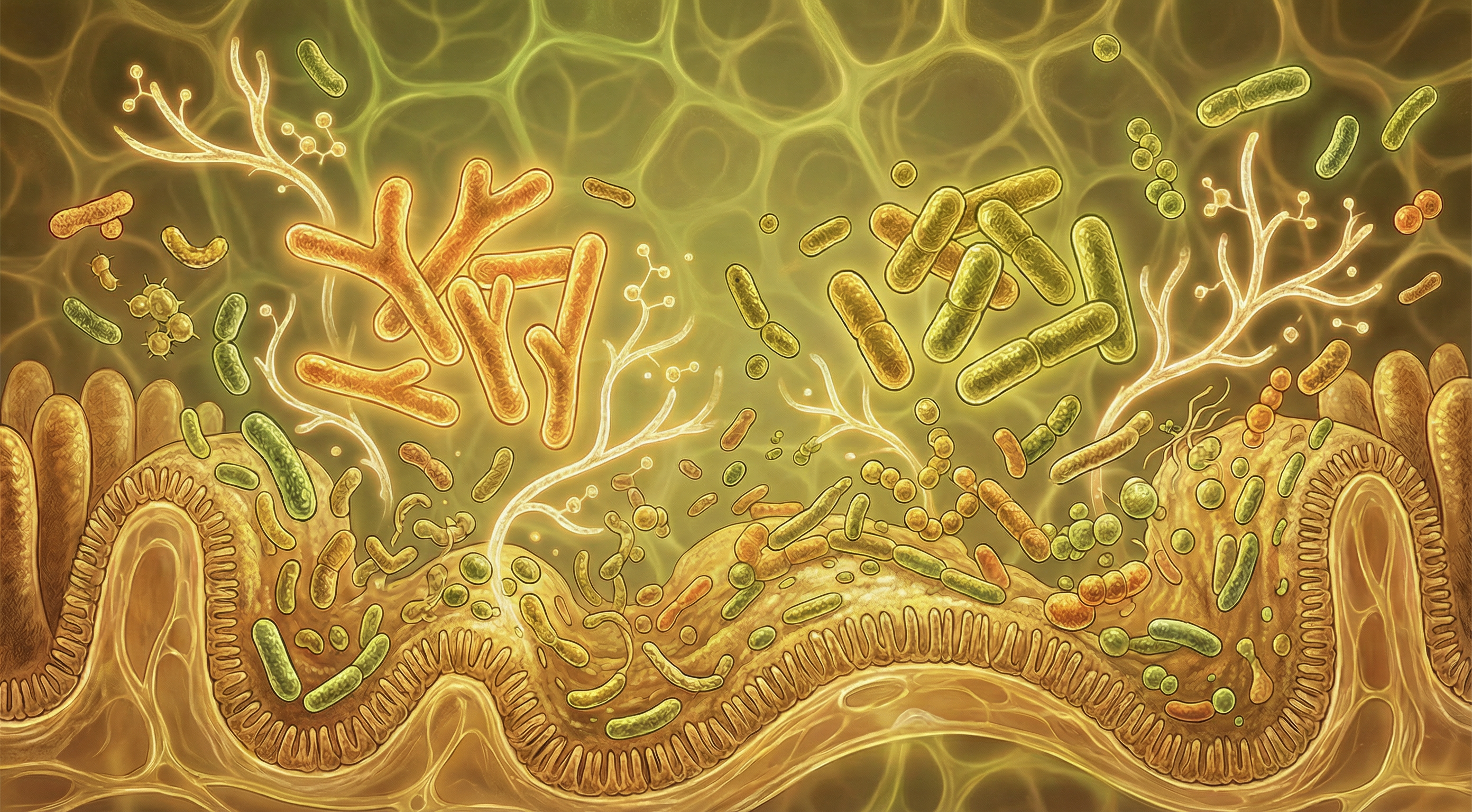

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) are short-chain fructans consisting of 2-10 fructose units linked by β(2→1) glycosidic bonds, typically with a terminal glucose unit[4]. As a lower-molecular-weight version of inulin, FOS shares many prebiotic properties but with distinct fermentation characteristics due to its shorter chain length. FOS occurs naturally in many plants, with the highest concentrations found in yacon root, and is also produced commercially through partial enzymatic hydrolysis of chicory inulin or enzymatic synthesis from sucrose.

Mechanism of Action

FOS resists digestion in the small intestine due to the β-glycosidic bonds that human digestive enzymes cannot hydrolyze[5]. Upon reaching the colon, FOS is rapidly and selectively fermented by beneficial bacteria, particularly Bifidobacterium species. The mechanism involves:

- Selective utilization: Bifidobacteria possess β-fructosidase enzymes that efficiently cleave the β(2→1) linkages in FOS, giving them a competitive advantage over other gut bacteria

- Rapid fermentation: The shorter chain length of FOS compared to inulin results in faster fermentation, primarily in the proximal colon

- SCFA production: Fermentation yields short-chain fatty acids, predominantly acetate and lactate, with subsequent conversion to butyrate through bacterial cross-feeding

The landmark 1995 study by Gibson and colleagues established the selective bifidogenic nature of FOS, demonstrating that it stimulates bifidobacteria while maintaining potentially pathogenic clostridia at low levels[2].

Effects on Gut Microbiome

A comprehensive 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials confirmed FOS's prebiotic effects[1]. Key findings include:

Primary Effects

- Bifidobacterium increase: Meta-analysis showed a significant weighted mean difference of 0.579 log CFU/g (95% CI: 0.444-0.714) in Bifidobacterium counts with FOS supplementation

- Dose-dependent response: Higher doses (>5g/day) produced greater effects (WMD: 1.116) compared to lower doses (≤5g/day; WMD: 0.521)

- Duration matters: Interventions longer than 4 weeks showed more pronounced effects (WMD: 0.841) than shorter interventions

No Significant Changes

- Lactobacillus counts did not significantly change with FOS supplementation

- Enterobacteriaceae (potential pathogens) levels remained stable

- Total anaerobe counts were unchanged, indicating selective rather than general stimulation

The dose-response relationship has been further characterized, with studies showing that fecal bifidobacteria increase dose-dependently with FOS intake from 2.5g to 10g daily[3].

Clinical Evidence

Gut Health Benefits

FOS supplementation has demonstrated several clinically meaningful effects:

- Improved bowel regularity and stool consistency

- Reduced gastrointestinal transit time

- Enhanced calcium and magnesium absorption

- Potential protective effects against intestinal infections

Immune Modulation

A systematic review on FOS's immunomodulatory effects found evidence for[6]:

- Reduced inflammatory markers

- Enhanced gut barrier function

- Modulation of cytokine production

- Improved antioxidant status

Tolerability

The meta-analysis found no significant differences between FOS and placebo groups for adverse gastrointestinal symptoms including[1]:

- Bloating

- Flatulence

- Abdominal pain

- Borborygmi (stomach rumbling)

This confirms that FOS at doses up to 15g/day is well-tolerated by healthy adults, although individuals with IBS or carbohydrate sensitivities may require lower doses.

Dosage and Usage

Based on clinical evidence, the optimal FOS dosage is:

- Minimum effective dose: 2.5g daily for measurable bifidogenic effects

- Optimal range: 7.5-15g daily for more pronounced effects[1]

- Duration: At least 4 weeks for full effects to manifest

Practical Recommendations

- Start with 2.5-5g daily and gradually increase

- Divide doses between meals

- Maintain consistent daily intake

- Allow 4+ weeks for microbiome adaptation

FOS vs. Inulin

While FOS and inulin are chemically related, they have distinct characteristics:

| Property | FOS | Inulin |

|---|---|---|

| Chain length | 2-10 units | 10-60 units |

| Fermentation rate | Faster (proximal colon) | Slower (throughout colon) |

| Sweetness | ~30-50% of sucrose | ~10% of sucrose |

| Primary benefit | Rapid Bifidobacterium growth | Sustained prebiotic effect |

Many commercial products combine FOS and inulin to provide both rapid and sustained prebiotic effects throughout the colon.

Food Sources

FOS occurs naturally in many plant foods[5]:

High FOS Content

- Yacon root (highest concentration)

- Chicory root

- Jerusalem artichoke

- Blue agave

Moderate FOS Content

- Onions

- Garlic

- Leeks

- Asparagus

- Bananas

- Wheat and barley (small amounts)

Safety Considerations

FOS is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) and has been used extensively in foods and supplements. However:

- High fermentability: Can cause gas and bloating in sensitive individuals

- FODMAP content: May not be suitable for those following strict low-FODMAP diets

- Individual variation: Responses vary based on baseline microbiome composition

Summary

Fructooligosaccharides represent one of the most well-characterized prebiotics, with robust meta-analytic evidence supporting their selective bifidogenic effects. The dose-dependent increase in Bifidobacterium species, combined with good tolerability at therapeutic doses, makes FOS a valuable tool for supporting gut microbiome health. For optimal results, doses of 7.5-15g daily for at least 4 weeks are recommended, with gradual introduction to minimize potential gastrointestinal symptoms.

Dosage Guidelines

Recommended Dosage

2.5-10g daily

Start with a lower dose and gradually increase to minimize digestive discomfort. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized recommendations.

References

- Dou Y, Yu X, Luo Y, et al.. Effect of Fructooligosaccharides Supplementation on the Gut Microbiota in Human: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022;14(16):3298. doi:10.3390/nu14163298

- Gibson GR, Beatty ER, Wang X, Cummings JH. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(4):975-982. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(95)90192-2

- Bouhnik Y, Raskine L, Simoneau G, et al.. The capacity of short-chain fructo-oligosaccharides to stimulate faecal bifidobacteria: A dose-response relationship study in healthy humans. Nutrition Journal. 2006;5:8. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-5-8

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al.. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;14(8):491-502. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

- Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: Mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417-1435. doi:10.3390/nu5041417

- Costa GT, Vasconcelos Q, Aragão GF. Fructooligosaccharides on inflammation, immunomodulation, oxidative stress, and gut immune response: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews. 2022;80(3):709-722. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab115