Rheumatoid Arthritis

Explore the complex relationship between the microbiome and rheumatoid arthritis, and discover evidence-based approaches for managing symptoms through gut health.

Common Symptoms

Microbiome Imbalances

Research has identified the following microbiome patterns commonly associated with this condition:

- Increased Prevotella copri

- Decreased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

- Altered microbial diversity

- Increased intestinal permeability

Understanding Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by persistent inflammation of the joints, leading to pain, swelling, stiffness, and eventual joint damage. Unlike osteoarthritis, which results from mechanical wear and tear, RA occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's own tissues, particularly the synovial membrane that lines the joints.

While RA primarily affects the joints, it's a systemic condition that can impact multiple organs and systems throughout the body. Common symptoms include joint pain and swelling (typically symmetrical), morning stiffness lasting more than an hour, fatigue, and low-grade fever. Over time, untreated RA can lead to joint deformity, disability, and complications affecting the heart, lungs, and other organs.

The exact cause of RA remains incompletely understood, but research increasingly points to a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and—significantly—alterations in the microbiome, particularly in the gut.

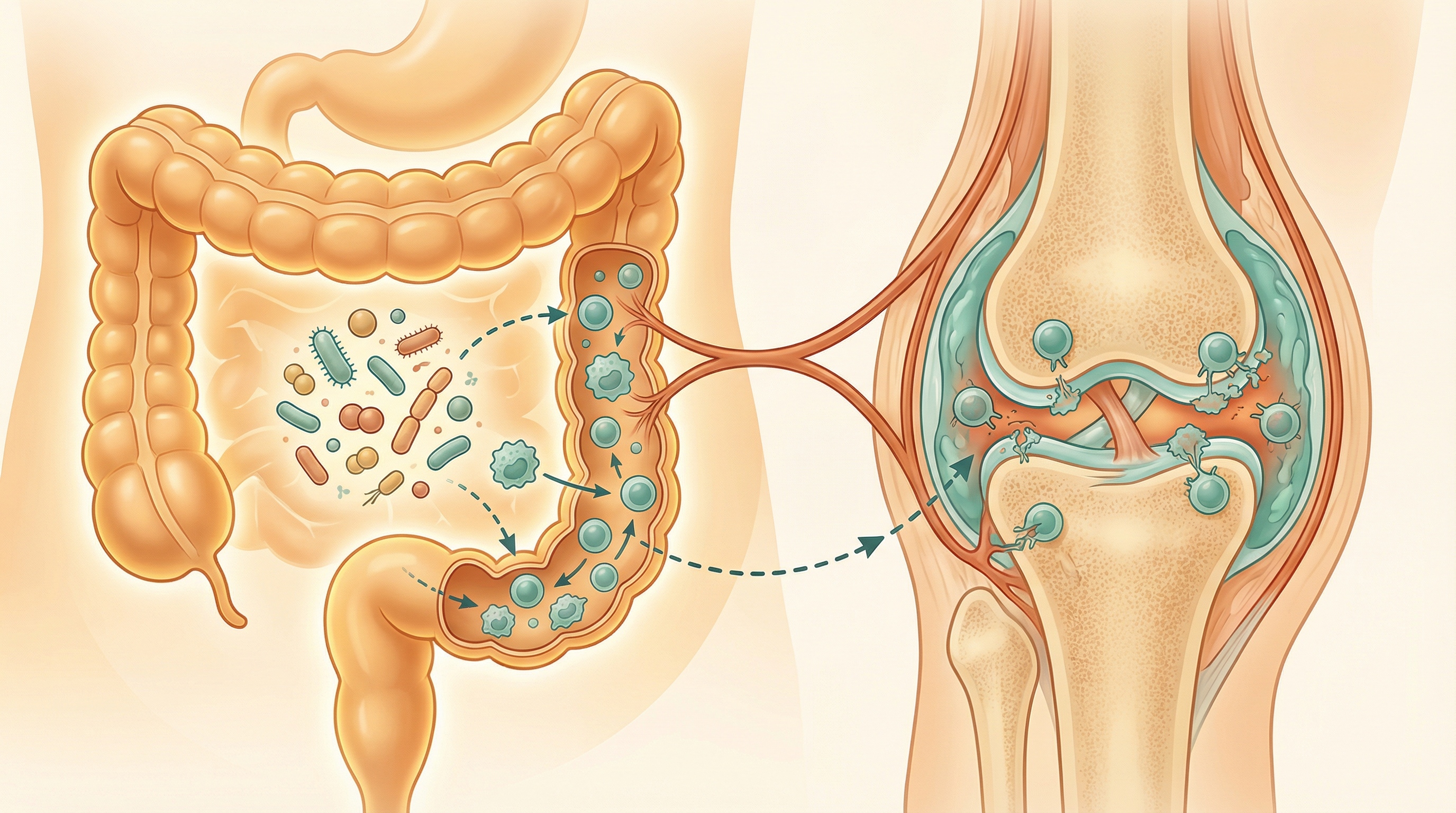

The Microbiome-Rheumatoid Arthritis Connection

A growing body of evidence suggests that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Gut microbiota dysbiosis was associated with rheumatic diseases, principally with potentially non-specific, shared alterations of microbes.[1] Significant alterations in gut microbiota composition are observed in RA compared to healthy individuals, suggesting a direct association between gut dysbiosis and RA pathogenesis through the gut-joint axis.[2] Multiple studies have documented significant differences between the gut microbiomes of RA patients and healthy individuals:

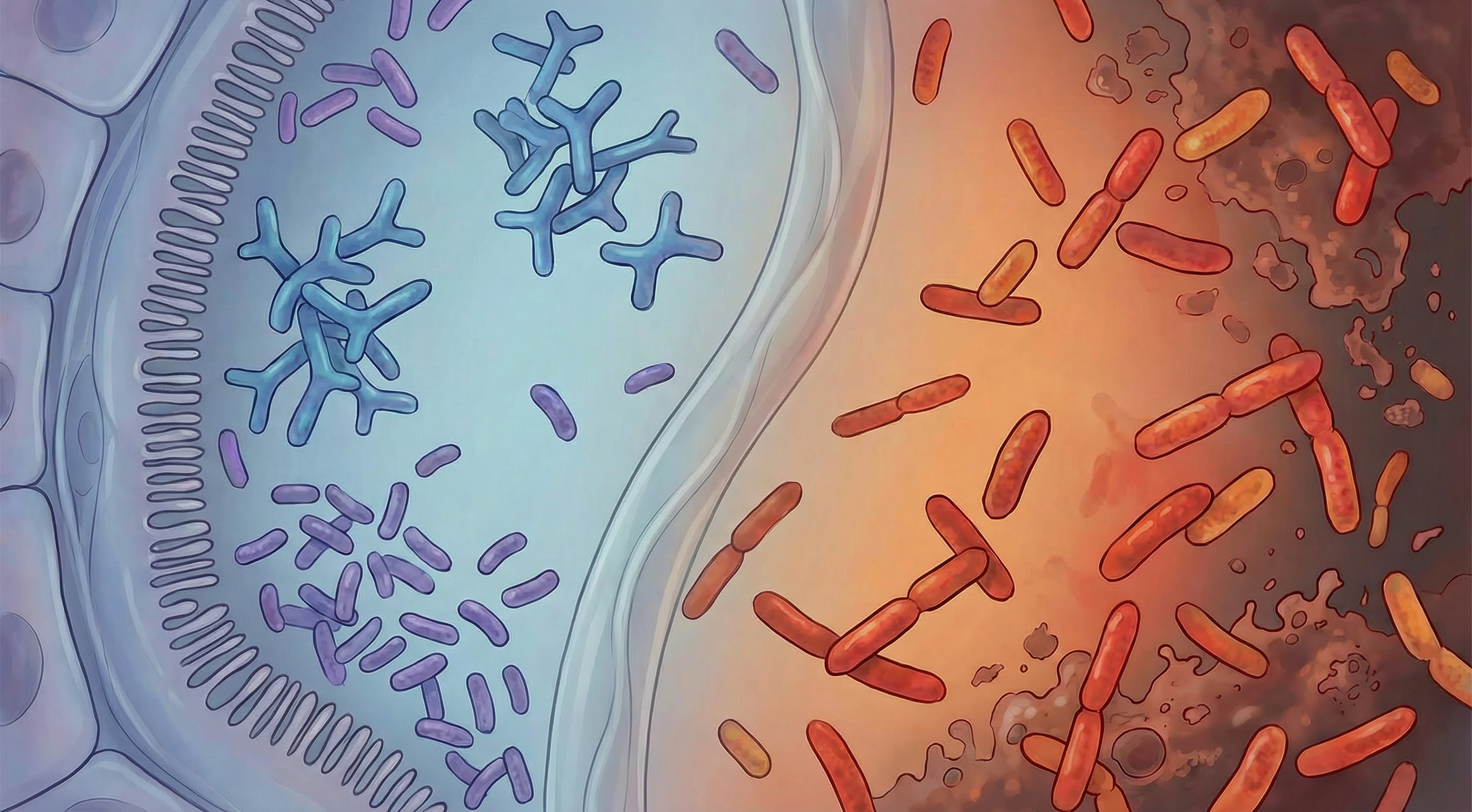

Altered Microbial Composition

RA patients typically show decreased microbial diversity and specific taxonomic changes, including increased abundance of Prevotella copri and decreased levels of beneficial bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.

Mucosal Immunity

The gut microbiome shapes mucosal immunity, influencing the balance between pro-inflammatory and regulatory immune responses. Dysbiosis can promote the Th17-dominant immune profile characteristic of RA.

Molecular Mimicry

Certain bacterial proteins share structural similarities with human proteins, potentially triggering autoimmune responses through molecular mimicry. This mechanism may contribute to the development of RA-associated autoantibodies.

Intestinal Permeability

Microbiome alterations can increase gut permeability, allowing bacterial components to enter circulation and potentially trigger systemic inflammation and autoimmunity.

A Mendelian randomization study demonstrated causal associations between gut microbiota and rheumatoid arthritis, finding that increased abundance of Catenibacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Ruminiclostridium 6 was associated with higher RA risk, while Lachnospiraceae (UCG008) had a protective effect.[3] At RA disease onset, patients had increased intestinal microbes including Prevotella copri compared to healthy controls, with expansion correlating with increased proinflammatory IL-17, while short-chain fatty acids showed protective effects.

Key Microorganisms in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Several specific microorganisms have been implicated in RA pathogenesis or protection:

Prevotella copri

Impact: Potentially harmful, often increased in early RA Function: May promote Th17 immune responses and inflammation; associated with new-onset RA and ACPA-negative RA. Prevotella copri is strongly associated with new-onset RA and exhibits molecular mimicry with host antigens, while dysbiosis affects regulatory T cells and cytokine levels, influencing RA disease activity.[4]

Porphyromonas gingivalis

Impact: Harmful, associated with periodontitis and RA Function: Produces peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) enzyme that can citrullinate proteins, potentially triggering anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs)

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

Impact: Protective, typically depleted in RA Function: Major butyrate producer with potent anti-inflammatory properties; helps maintain intestinal barrier integrity

Collinsella aerofaciens

Impact: Potentially harmful, increased in RA Function: Associated with increased intestinal permeability and altered expression of tight junction proteins

The relationship between these microorganisms and RA is complex and likely involves multiple mechanisms. For example, P. gingivalis from the oral microbiome has been linked to RA through its ability to citrullinate proteins, potentially triggering the production of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) that are highly specific for RA. Meanwhile, gut bacteria like Prevotella copri may influence systemic inflammation and immune responses that contribute to joint damage.

Microbiome-Based Approaches for Rheumatoid Arthritis Management

While conventional RA treatments focus on suppressing inflammation and immune responses, microbiome-targeted approaches are emerging as complementary strategies:

Anti-Inflammatory Diet

Dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols, and fiber, can promote beneficial gut bacteria and reduce systemic inflammation. Studies show that these diets may help reduce RA symptoms and improve quality of life. Evidence Level: Moderate

Probiotics

Specific probiotic strains, particularly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, have shown promise in reducing inflammatory markers and improving symptoms in RA patients. Clinical studies reveal significantly decreased Lactobacteria and increased opportunistic Enterococci and Clostridia in RA patients, with dysbiotic patterns reversible through probiotics and dietary interventions.[5] Effects appear to be strain-specific and may vary between individuals. Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

Prebiotics

Dietary fibers that selectively feed beneficial bacteria can improve gut microbiome composition and reduce inflammation. Inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), and resistant starch have shown particular promise for modulating immune responses relevant to RA. Evidence Level: Preliminary

Periodontal Health

Given the link between periodontal disease (particularly P. gingivalis infection) and RA, maintaining good oral hygiene and treating periodontal disease may help reduce RA risk or activity in some patients. Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

It's important to note that these microbiome-based approaches should be considered complementary to, not replacements for, conventional RA treatments. The optimal approach likely involves integrating multiple strategies tailored to individual patient characteristics and microbiome profiles.

The Mucosal Origins Hypothesis

A leading theory in RA pathogenesis is the "mucosal origins hypothesis," which proposes that RA may begin at mucosal surfaces—particularly the gut, oral cavity, and lungs—years before joint symptoms appear.

Key Elements of the Mucosal Origins Hypothesis

- Initial Trigger: Environmental factors (smoking, microbiome changes, infections) at mucosal sites trigger local inflammation and immune responses

- Autoantibody Production: These responses lead to the production of autoantibodies like rheumatoid factor (RF) and ACPAs at mucosal sites

- Systemic Spread: Autoantibodies and activated immune cells enter circulation, eventually targeting the joints

- Clinical Disease: Additional factors (genetic, environmental) lead to the transition from subclinical autoimmunity to clinical RA

This hypothesis explains several observations, including the presence of autoantibodies years before clinical RA, the association between RA and conditions affecting mucosal sites (periodontitis, bronchiectasis), and the altered microbiome composition in early RA. It also suggests potential opportunities for early intervention targeting mucosal immunity and the microbiome.

Future Directions in Microbiome-Based RA Research

The field of microbiome-RA research is rapidly evolving, with several promising directions:

Precision Medicine Approaches

Research is increasingly focusing on identifying specific microbiome signatures that might predict disease onset, progression, or treatment response, potentially enabling more personalized approaches to RA management.

Novel Interventions

Beyond traditional probiotics, researchers are exploring next-generation approaches including:

- Engineered live biotherapeutics designed to target specific aspects of RA pathophysiology

- Postbiotics derived from beneficial microorganisms that may have direct anti-inflammatory effects

- Targeted antimicrobials that selectively reduce potentially harmful bacteria while preserving beneficial ones

Prevention Strategies

Understanding the role of the microbiome in pre-clinical RA opens possibilities for prevention, particularly in high-risk individuals with genetic susceptibility or first-degree relatives of RA patients.

The integration of microbiome science into RA management represents a paradigm shift toward addressing underlying biological mechanisms rather than just suppressing symptoms. While much research remains to be done, the evidence to date suggests that nurturing a healthy microbiome may be an important component of comprehensive RA care.

Research Summary

A growing body of evidence suggests that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Multiple studies have documented significant differences between the gut microbiomes of RA patients and healthy individuals.

References

- Xu JW, Wang X, Chu XJ, et al.. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eBioMedicine. 2022;80:104037. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104037 ↩

- Kumar S.. Exploring the gut-joint axis: The role of gut dysbiosis in rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis and therapeutic potential. International Immunopharmacology. 2025;147:112526. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.112526 ↩

- Wei F, Zhao M, Sun X, et al.. Causal associations between gut microbiota and rheumatoid arthritis: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104(22):e42596. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000042596 ↩

- Muruganandam A, Migliorini F, Jeyaraman N, et al.. Molecular Mimicry Between Gut Microbiome and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Current Concepts. Medical Sciences (Basel). 2024;12(4):72. doi:10.3390/medsci12040072 ↩

- Yang Y, Hong Q, Zhang X, Liu Z.. Rheumatoid arthritis and the intestinal microbiome: probiotics as a potential therapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;15:1331486. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1331486 ↩