SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth)

Explore the causes, symptoms, and microbiome connections of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), and discover evidence-based approaches for managing this condition.

Common Symptoms

Microbiome Imbalances

Research has identified the following microbiome patterns commonly associated with this condition:

- Bacterial overgrowth in small intestine

- Reduced microbial diversity in large intestine

- Disrupted small intestinal motility

Understanding SIBO and the Microbiome Connection

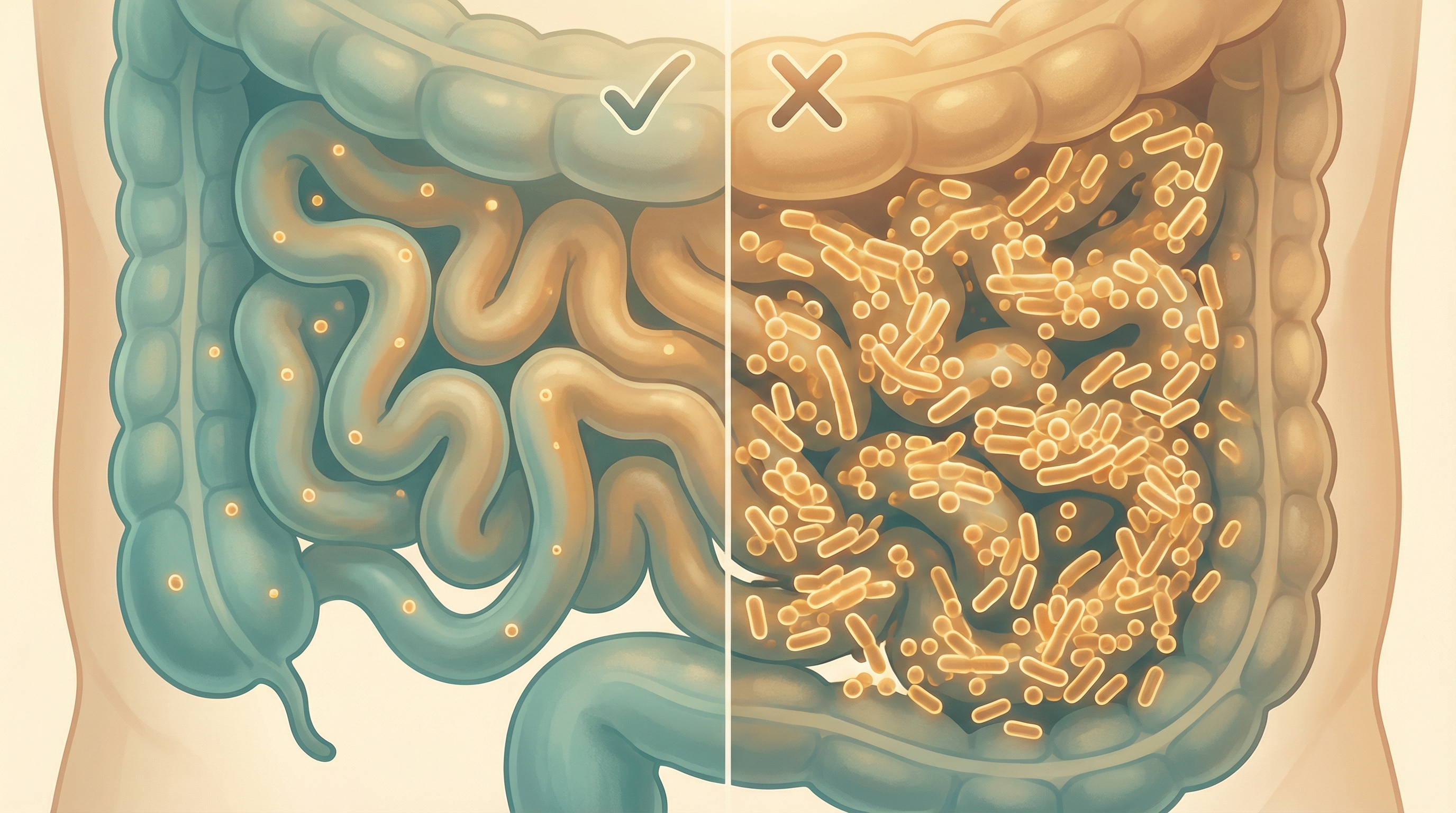

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition characterized by excessive bacteria in the small intestine.[1] Unlike the colon, which contains trillions of bacteria, the small intestine normally has relatively few bacteria. When bacteria that typically reside in the colon migrate upward and colonize the small intestine, or when the normal small intestinal bacteria grow excessively, SIBO occurs. SIBO is characterized by an increase in Enterobacteriaceae abundance and enrichment of gas-producing pathways that correlate with symptom severity.[2]

This bacterial overgrowth can interfere with normal digestion and absorption of nutrients, leading to a range of uncomfortable symptoms and potential nutritional deficiencies. SIBO is increasingly recognized as an underlying factor in many cases of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Types of SIBO

SIBO is typically classified into three main types based on the predominant gas produced by the overgrown bacteria:

Hydrogen-Dominant SIBO

- Caused by bacteria that primarily produce hydrogen gas

- Often associated with diarrhea-predominant symptoms

- Typically diagnosed via hydrogen breath testing

- Common bacterial culprits include species of Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus

Methane-Dominant SIBO (also called Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth or IMO)

- Caused by archaea (particularly Methanobrevibacter smithii) that produce methane gas

- Strongly associated with constipation and slower transit time

- Diagnosed via methane breath testing

- Methane gas directly slows intestinal motility, creating a self-perpetuating cycle

Hydrogen Sulfide-Dominant SIBO

- Caused by sulfate-reducing bacteria that produce hydrogen sulfide gas

- Often associated with diarrhea and more severe gastrointestinal symptoms

- May cause a rotten egg smell to gas

- More difficult to diagnose as standard breath tests don't measure hydrogen sulfide

- Emerging research suggests connections to inflammatory conditions

Causes and Risk Factors for SIBO

Several factors can disrupt the normal protective mechanisms that prevent bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine:

Impaired Motility

The migrating motor complex (MMC), a pattern of electromechanical activity that sweeps through the intestine between meals, acts as a "housekeeping" mechanism to clear bacteria. Conditions that impair the MMC increase SIBO risk:

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Hypothyroidism

- Scleroderma

- Certain medications (particularly opioids and proton pump inhibitors)

- Post-infectious IBS

Structural Abnormalities

Physical alterations to the intestinal tract can create areas where bacteria can accumulate:

- Previous abdominal surgery

- Intestinal diverticula

- Strictures or adhesions

- Blind loops created by surgery

Reduced Gastric Acid

Stomach acid helps control bacterial populations. Conditions or medications that reduce acid can contribute to SIBO:

- Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers

- Gastric bypass surgery

- Atrophic gastritis

Immunodeficiency

The immune system helps regulate gut bacteria. Compromised immunity can lead to bacterial overgrowth:

- Common variable immunodeficiency

- IgA deficiency

- HIV/AIDS

- Immunosuppressive medications

Other Risk Factors

- Aging (reduced motility and digestive enzyme production)

- Chronic stress (affects gut motility and immune function)

- Recurrent antibiotic use (disrupts normal microbiome balance)

- Chronic pancreatitis (reduced digestive enzymes)

The Microbiome Disruption in SIBO

SIBO represents a significant disruption to the normal microbiome pattern of the gastrointestinal tract:

Small Intestine Dysbiosis

- Excessive bacterial counts (normally <10³ colony-forming units/mL, in SIBO >10⁵ CFU/mL)

- Presence of colonic-type bacteria in the small intestine

- Reduced microbial diversity in some cases

- Potential overgrowth of pathogenic or opportunistic species

Large Intestine Consequences

- Altered colonic microbiome composition

- Potential reduction in beneficial species

- Changes in short-chain fatty acid production

- Disrupted bile acid metabolism

Systemic Effects

- Increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut")

- Bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation

- Immune system activation

- Potential connections to extraintestinal symptoms (fatigue, brain fog, joint pain)

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

SIBO can manifest with a wide range of symptoms, many of which overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders:

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

- Bloating and abdominal distension (often worse after meals)

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

- Excessive flatulence

- Diarrhea (more common in hydrogen-dominant SIBO)

- Constipation (more common in methane-dominant SIBO)

- Nausea

- Heartburn or reflux

- Food intolerances (particularly to fermentable carbohydrates)

Nutritional Consequences

- Malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K)

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Iron deficiency

- Weight loss (in severe cases)

- Carbohydrate malabsorption

Extraintestinal Manifestations

- Fatigue

- Brain fog or cognitive difficulties

- Headaches

- Skin issues (rashes, eczema)

- Joint pain

- Mood disturbances (anxiety, depression)

Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnosing SIBO can be challenging due to overlapping symptoms with other conditions and limitations of current testing methods:

Breath Testing

The most common diagnostic approach:

- Lactulose or glucose breath test

- Measures hydrogen and/or methane gas produced by bacteria

- Newer tests also measure hydrogen sulfide

- Limitations include false positives/negatives and lack of standardization

Small Intestinal Aspirate and Culture

The gold standard but rarely performed due to invasiveness:

- Requires endoscopy

- Samples fluid from small intestine for bacterial culture

- Diagnostic threshold: >10⁵ colony-forming units/mL

- Limitations include sampling errors and difficulty culturing all bacteria

Symptom-Based Diagnosis

Often used in clinical practice:

- Characteristic symptom pattern

- Response to empiric treatment

- Exclusion of other conditions

Biomarkers

Emerging approaches:

- Urinary organic acids

- Serum markers of bacterial translocation

- Fecal calprotectin (to rule out inflammatory conditions)

Microbiome-Based Approaches for SIBO Management

Treatment of SIBO typically follows a multi-phase approach:

Phase 1: Reduce Bacterial Overgrowth

Pharmaceutical Antimicrobials

- Rifaximin (Xifaxan): Non-absorbable antibiotic, particularly effective for hydrogen-dominant SIBO. Treatment with rifaximin for 2 weeks provides significant relief of IBS symptoms, bloating, abdominal pain, and loose or watery stools.[3] A systematic review confirmed rifaximin achieves an overall eradication rate of 70.8% according to intention-to-treat analysis.[4]

- Evidence Level: Strong

- Neomycin: Often combined with rifaximin for methane-dominant SIBO

- Evidence Level: Moderate

- Other antibiotics: Ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, doxycycline. IBS patients with SIBO are significantly more likely to respond to antibiotic treatment than those without SIBO (relative risk 2.07).[5]

- Evidence Level: Moderate

Herbal Antimicrobials

Natural alternatives with antimicrobial properties. A 2025 network meta-analysis identified berberine as the most effective overall option for SIBO treatment, while rifaximin with prokinetics is recommended for those with functional gastrointestinal disorders.[6]

- Berberine-containing herbs: Oregon grape, goldenseal, barberry

- Allicin (from garlic)

- Oil of oregano

- Neem

- Combination protocols: Often used in clinical practice

- Evidence Level: Moderate

Phase 2: Restore Motility

Prokinetic Agents

Medications and supplements that improve intestinal motility:

- Pharmaceutical options: Low-dose erythromycin, prucalopride, low-dose naltrexone

- Natural options: Ginger, 5-HTP, iberogast, motilpro

- Evidence Level: Moderate to Strong

Phase 3: Dietary Modifications

Therapeutic Diets

Several dietary approaches can help manage SIBO:

- Low FODMAP Diet: Reduces fermentable carbohydrates

- Evidence Level: Strong

- Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD): Eliminates complex carbohydrates and refined sugars

- Evidence Level: Moderate

- Elemental Diet: Pre-digested nutrients absorbed in upper small intestine

- Evidence Level: Strong (but challenging to implement)

- SIBO Specific Food Guide: Combines aspects of multiple approaches

- Evidence Level: Preliminary

Phase 4: Support and Prevent Recurrence

Digestive Support

- Digestive enzymes: Aid in breaking down food

- Bile acid supplementation: Particularly for fat malabsorption

- Hydrochloric acid (if deficient): Supports protein digestion and acts as antimicrobial

- Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

Targeted Probiotics

Certain probiotic strains may help prevent SIBO recurrence:

- Saccharomyces boulardii: Yeast-based probiotic that doesn't colonize the small intestine

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus: May help restore normal gut function

- Soil-based organisms: Spore-forming probiotics that may be better tolerated

- Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate (strain-specific)

Gut Healing Compounds

- L-glutamine: Amino acid that fuels intestinal cells

- Zinc carnosine: Supports intestinal barrier function

- Collagen peptides: Provide building blocks for intestinal repair

- Evidence Level: Preliminary to Moderate

Clinical Evidence and Research Highlights

Recent studies have provided important insights into SIBO management:

A systematic review with meta-analysis confirmed that rifaximin is effective and safe for SIBO treatment, achieving an overall eradication rate of 70.8%.[4]

The landmark NEJM trial demonstrated that rifaximin therapy for 2 weeks provided significant relief of IBS symptoms in patients without constipation, supporting the role of bacterial overgrowth in symptom generation.[3]

A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis found that antibiotics are effective for symptom relief in SIBO, with IBS patients with SIBO significantly more likely to respond to antibiotic treatment.[5]

A 2025 network meta-analysis comparing diverse therapeutic regimens found that optimal SIBO treatment should be tailored to patient comorbidities, with berberine identified as the most effective overall option.[6]

The Importance of Addressing Root Causes

Long-term management of SIBO requires identifying and addressing underlying factors:

- Motility disorders: Working with a gastroenterologist to improve MMC function

- Structural issues: Surgical correction when appropriate

- Medication review: Minimizing use of medications that predispose to SIBO

- Stress management: Addressing the gut-brain connection

- Immune support: Identifying and treating immunodeficiencies

Future Directions in SIBO Research and Treatment

The field of SIBO research is rapidly evolving, with several promising developments:

- Improved diagnostic methods: More accurate and accessible testing

- Targeted antimicrobials: Agents that affect specific bacterial populations

- Microbiome restoration: Approaches to restore normal small intestinal microbiome

- Biofilm disruptors: Compounds that break down protective bacterial biofilms

- Personalized treatment protocols: Tailored approaches based on SIBO subtype and individual factors

Key Takeaways

- SIBO represents a significant disruption to the normal microbiome pattern of the gastrointestinal tract

- Different SIBO subtypes (hydrogen, methane, hydrogen sulfide) present with varying symptoms and require different treatment approaches

- Effective SIBO management typically requires a multi-phase approach: reduce bacterial overgrowth, restore motility, modify diet, and prevent recurrence

- Addressing underlying root causes is essential for long-term management and prevention of recurrence

- Emerging research is paving the way for more targeted, personalized approaches to SIBO treatment

Research Summary

Research indicates that SIBO involves an abnormal increase in the total number of bacteria in the small intestine, and/or changes in the types of bacteria present. These bacteria typically belong to species that should be primarily found in the colon. Studies show connections between SIBO and conditions like IBS, with treatment approaches focusing on addressing the overgrowth and restoring normal gut motility.

References

- Bures J, et al.. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(24):2978-2990. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978 ↩

- Sharabi E, Rezaie A.. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2024;26(11):227-233. doi:10.1007/s11908-024-00847-7 ↩

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al.. Rifaximin Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome without Constipation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(1):22-32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1004409 ↩

- Gatta L, Scarpignato C.. Systematic review with meta-analysis: rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2017;45(5):604-616. doi:10.1111/apt.13928 ↩

- Takakura W, Rezaie A, Chey WD, et al.. Symptomatic Response to Antibiotics in Patients With Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2024;30(1):7-16. doi:10.5056/jnm22187 ↩

- Zhang Q, Li H, Chen C, et al.. Comparative efficacy of diverse therapeutic regimens for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a systematic network meta-analysis. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2025;18:17562848251399033. doi:10.1177/17562848251399033 ↩