Aspergillus fumigatus

Overview

Aspergillus fumigatus is a ubiquitous, saprophytic filamentous fungus that plays a significant role in global carbon and nitrogen recycling. While its primary ecological niche is soil and decaying vegetation, A. fumigatus produces small (2-3 μm), hydrophobic conidia that disperse easily into the air and can survive a broad range of environmental conditions. These characteristics make A. fumigatus one of the most prevalent fungal species in the environment, with its conidia being regularly inhaled by humans and animals.

Among the approximately 200 species in the genus Aspergillus, A. fumigatus is the primary causative agent of human infections, followed by A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger, and A. nidulans. Despite constant human exposure to A. fumigatus conidia, with estimates suggesting that humans inhale 500-5000 fungal spores daily, the development of Aspergillus-related diseases is relatively rare in immunocompetent individuals. This is primarily due to efficient clearance mechanisms in the respiratory tract and robust immune responses that prevent fungal establishment and growth.

However, A. fumigatus is a significant opportunistic pathogen in individuals with compromised immune systems or underlying respiratory conditions. It is responsible for a spectrum of diseases collectively known as aspergillosis, which range from allergic reactions to life-threatening invasive infections. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is the most severe form, primarily affecting severely immunocompromised patients such as those with hematological malignancies, solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, individuals on prolonged corticosteroid therapy, and those with genetic immunodeficiencies. Mortality rates for invasive aspergillosis range from 40% to 90% in high-risk populations, depending on factors such as host immune status, the site of infection, and the treatment regimen applied.

The pathogenicity of A. fumigatus is multifactorial, involving various virulence factors that enable the fungus to survive and thrive in the human host. These include its small conidial size allowing deep penetration into the respiratory tract, thermotolerance permitting growth at human body temperature, cell wall components that protect against host defenses, and the production of various enzymes and secondary metabolites that facilitate tissue invasion and nutrient acquisition.

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition of A. fumigatus as a significant pathogen in emerging at-risk populations, including patients with cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and those with severe viral infections. Additionally, the rise of antifungal resistance in A. fumigatus strains presents a growing challenge for clinical management of aspergillosis.

Understanding the complex interactions between A. fumigatus and the human host is crucial for developing more effective diagnostic tools, therapeutic strategies, and preventive measures for aspergillosis. As an opportunistic pathogen that primarily affects individuals with compromised immunity or underlying conditions, A. fumigatus serves as an important model for studying host-pathogen interactions in the context of altered immune function.

Characteristics

Aspergillus fumigatus possesses several distinctive characteristics that contribute to its prevalence in the environment and its capacity to cause disease in susceptible hosts:

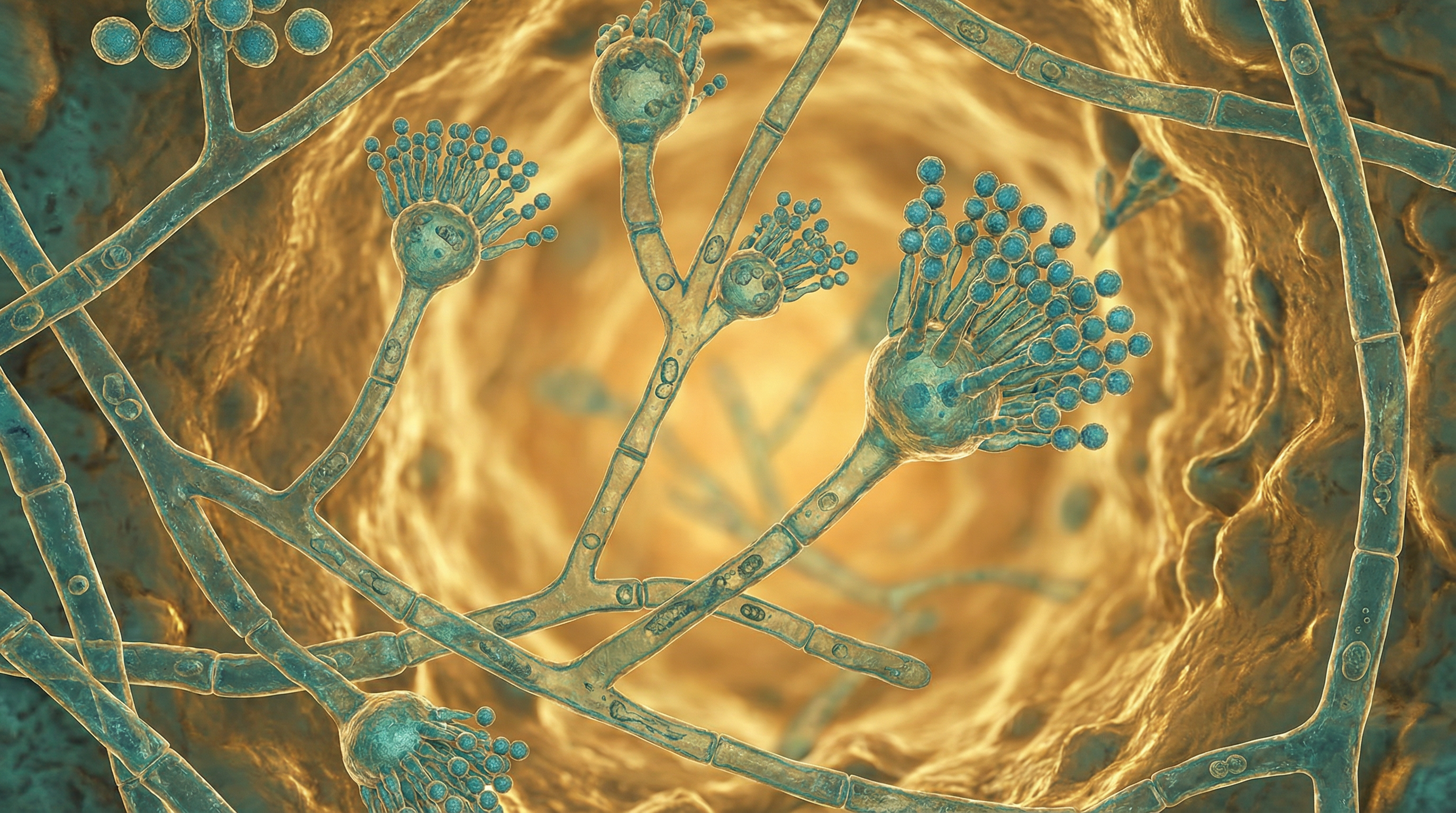

Morphological Features:

- Produces small (2-3 μm), blue-green echinulate (spiny) conidia

- Conidia extend in long chains from conidiophores that emerge from the vegetative mycelium

- Forms septate hyphae during growth, typically 2-3 μm in diameter

- Colonies appear blue-green to gray-green on laboratory media

- Demonstrates rapid growth, with colonies visible within 24-48 hours at optimal conditions

- Capable of forming biofilms on various surfaces, enhancing resistance to antifungal agents

- Produces characteristic flask-shaped conidiophores with a swollen vesicle bearing phialides

Cell Wall Structure:

- Possesses a complex, polysaccharide-based cell wall that provides physical protection and structural support

- Primarily composed of α-1,3-glucan, galactofuran, and mannan

- Contains melanin, which contributes to resistance against environmental stressors and host immune responses

- Dynamic structure that changes in response to environmental conditions

- Can upregulate β-glucan production under stress conditions (e.g., hypoxia) to thicken the cell wall

- Contains various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) recognized by host immune cells

- Surface decorated with rodlet proteins (hydrophobins) that contribute to conidial hydrophobicity

Reproductive Capabilities:

- Primarily reproduces asexually, producing abundant conidia for aerial dispersal

- Also capable of sexual reproduction, though this occurs less frequently in nature

- Sexual cycle involves mating between compatible strains to form cleistothecia containing ascospores

- Asexual reproduction is highly efficient, with a single colony capable of producing billions of conidia

- Conidia remain viable for extended periods under various environmental conditions

- Demonstrates genetic diversity through both sexual recombination and parasexual processes

- Capable of rapid adaptation through genetic mechanisms, contributing to antifungal resistance

Environmental Adaptations:

- Thermotolerant, capable of growing at temperatures ranging from 12°C to 55°C, with optimal growth at 37-42°C

- Tolerates a wide pH range (3.7-7.6), with optimal growth at slightly acidic pH

- Highly resistant to desiccation, allowing survival in dry environments

- Capable of utilizing various carbon and nitrogen sources for growth

- Demonstrates remarkable resistance to oxidative stress

- Adapts to low oxygen environments (hypoxia) through metabolic adjustments

- Survives exposure to various environmental toxins and pollutants

- Tolerates high osmotic pressure and salt concentrations

Metabolic Capabilities:

- Versatile metabolism allowing utilization of diverse nutrient sources

- Produces numerous hydrolytic enzymes (proteases, lipases, phospholipases) for nutrient acquisition

- Capable of degrading complex organic materials in the environment

- Efficient iron acquisition systems to overcome iron limitation in host environments

- Produces various secondary metabolites with diverse biological activities

- Capable of adapting metabolism in response to changing environmental conditions

- Utilizes acetate and other short-chain carbon sources during infection

- Possesses metabolic pathways for detoxification of harmful compounds

Virulence Factors:

- Small conidial size allows deep penetration into the respiratory tract

- Thermotolerance enables growth at human body temperature

- Produces various toxins and immunomodulatory compounds

- Secretes proteolytic enzymes that facilitate tissue invasion

- Contains cell wall components that protect against host immune responses

- Produces gliotoxin, a potent immunosuppressive compound

- Possesses mechanisms to evade or suppress host immune responses

- Capable of forming biofilms that enhance resistance to antifungal agents and host defenses

- Produces siderophores for iron acquisition in the iron-limited host environment

- Demonstrates phenotypic plasticity, allowing adaptation to diverse host niches

Genetic Features:

- Haploid genome of approximately 29.4 million base pairs

- Contains approximately 9,900 protein-coding genes

- Demonstrates considerable genetic diversity among clinical and environmental isolates

- Possesses multiple gene families involved in secondary metabolite production

- Contains numerous genes encoding transporters for nutrient acquisition and toxin efflux

- Genome includes multiple genes involved in stress response and adaptation

- Exhibits genomic plasticity, facilitating adaptation to diverse environments

- Contains genes for various virulence factors that contribute to pathogenicity

- Possesses genetic mechanisms for antifungal resistance development

Growth Characteristics:

- Rapid growth rate, with colonies visible within 24-48 hours under optimal conditions

- Optimal growth temperature of 37-42°C, coinciding with human body temperature

- Capable of growing on minimal media with limited nutrients

- Forms dense, filamentous colonies with abundant sporulation

- Demonstrates dimorphic growth, transitioning from conidia to hyphae during infection

- Growth is enhanced in aerobic conditions but can adapt to hypoxic environments

- Exhibits different growth morphologies depending on environmental conditions

- Forms specialized structures (e.g., conidiophores) for asexual reproduction

These characteristics collectively contribute to the ecological success of A. fumigatus as an environmental saprophyte and its capacity to cause disease in susceptible hosts. The fungus's ability to produce abundant airborne conidia, survive in diverse environments, grow at human body temperature, and evade or modulate host immune responses makes it a particularly effective opportunistic pathogen. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for developing strategies to prevent and treat A. fumigatus infections, particularly in vulnerable populations.

Role in Human Microbiome

Aspergillus fumigatus occupies a unique position in relation to the human microbiome, primarily as a transient colonizer rather than a permanent resident in most individuals:

Respiratory Tract Colonization:

- Regularly enters the respiratory tract through inhalation of airborne conidia

- In healthy individuals, conidia are efficiently cleared by mucociliary clearance and immune mechanisms

- May transiently colonize the upper respiratory tract without causing disease

- In individuals with structural lung abnormalities (e.g., cavities from tuberculosis), can establish persistent colonization

- Forms fungal balls (aspergillomas) in pre-existing lung cavities

- Colonizes the airways of patients with chronic respiratory conditions such as cystic fibrosis and asthma

- Colonization rates increase in individuals with compromised lung defenses

- Can persist in the respiratory tract of patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- Colonization often precedes invasive disease in immunocompromised hosts

- May contribute to the respiratory tract microbiome in certain patient populations

Interactions with Resident Microbiota:

- Competes with resident bacteria for space and nutrients in the respiratory tract

- Produces antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit bacterial growth

- Interacts with bacterial biofilms in the airways of patients with chronic respiratory diseases

- May alter the composition of the bacterial microbiome in the respiratory tract

- Certain bacteria can inhibit A. fumigatus growth through production of antimicrobial compounds

- Polymicrobial interactions in the lung can influence disease progression and severity

- Recent research suggests A. fumigatus can disbalance the murine lung microbiome, leading to enrichment of anaerobic bacteria

- Interactions with the microbiome may influence antifungal drug efficacy

- Dysbiosis of the respiratory microbiome may create conditions favorable for A. fumigatus colonization

- Synergistic or antagonistic relationships with other microbes can affect pathogenicity

Influence on Host Immunity:

- Exposure to A. fumigatus conidia stimulates innate and adaptive immune responses

- Regular exposure may contribute to the development of immunological tolerance in healthy individuals

- In susceptible individuals, can trigger allergic responses leading to conditions like allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Modulates local immune responses in the respiratory tract

- Chronic colonization can lead to persistent inflammation

- Produces immunomodulatory compounds that can suppress host immune responses

- Interactions with the host immune system can shape the composition of the respiratory microbiome

- Immune responses to A. fumigatus may affect susceptibility to other respiratory pathogens

- Contributes to the education of the immune system regarding fungal recognition

- May influence the development of respiratory allergies and hypersensitivities

Ecological Niche in the Human Host:

- Primarily occupies the respiratory tract, particularly the lungs and sinuses

- Can colonize the external auditory canal in some individuals

- Rarely found as part of the normal skin microbiota

- In immunocompromised hosts, can disseminate to various organs including the brain, heart, and kidneys

- Adapts to the unique microenvironment of the human respiratory tract

- Utilizes host-derived nutrients for growth and survival

- Occupies specific niches within the respiratory tract based on local conditions

- Adapts metabolism to the nutrient availability in the host environment

- Forms biofilms on respiratory epithelium and medical devices

- Demonstrates niche adaptation through expression of specific virulence factors

Temporal Dynamics:

- Typically present as a transient colonizer rather than a permanent resident

- Colonization patterns may change with alterations in host immunity or environmental exposure

- Seasonal variations in environmental spore concentrations affect exposure and colonization rates

- Long-term colonization may occur in individuals with chronic respiratory conditions

- Colonization can persist despite antifungal therapy in some cases

- Dynamics of colonization influenced by antibiotic use and other medical interventions

- Persistence in the host may lead to adaptation and increased virulence

- Colonization patterns may change throughout the course of chronic diseases

- Repeated exposure and clearance cycles occur in most individuals

- Establishment in the host often requires repeated exposure or compromised host defenses

Contribution to Disease States:

- Primary role as an opportunistic pathogen rather than a commensal organism

- Causes a spectrum of diseases collectively known as aspergillosis

- In allergic individuals, contributes to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Forms aspergillomas in pre-existing lung cavities

- Causes invasive aspergillosis in severely immunocompromised hosts

- Contributes to exacerbations of chronic respiratory conditions

- May worsen lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis and other chronic lung diseases

- Chronic colonization associated with progressive lung damage in some patients

- Contributes to the pathogenesis of fungal asthma

- Presence in the respiratory tract may predispose to bacterial infections

Adaptation to the Host Environment:

- Adapts to the unique conditions of the human respiratory tract

- Modifies gene expression in response to host factors

- Alters metabolism to utilize available nutrients in the host

- Develops resistance to host defense mechanisms

- Demonstrates phenotypic plasticity in different host niches

- Adapts to hypoxic conditions in the lung microenvironment

- Modifies cell wall composition in response to host immune pressures

- Upregulates virulence factors during host colonization

- Develops antifungal resistance during prolonged exposure to antifungal drugs

- Shows evidence of host-specific adaptation in chronic infections

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications:

- Detection in respiratory samples may represent contamination, colonization, or infection

- Distinguishing between colonization and infection is clinically challenging

- Presence in the respiratory tract may influence treatment decisions

- Colonization may serve as a reservoir for subsequent invasive disease

- Eradication of colonization is difficult and often unsuccessful

- Monitoring of colonization important in high-risk patients

- Microbiome-based approaches may offer new strategies for preventing colonization

- Understanding interactions with the respiratory microbiome may lead to novel therapeutic approaches

- Probiotic strategies being explored to prevent A. fumigatus colonization

- Personalized approaches based on microbiome composition may improve management

Unlike many components of the human microbiome, A. fumigatus is not considered a normal resident microbe in most individuals. Its relationship with the human host is primarily that of a transient colonizer or opportunistic pathogen, with its presence in the respiratory tract often representing a precarious balance between exposure, host clearance mechanisms, and fungal virulence factors. In individuals with compromised immunity or underlying respiratory conditions, this balance can shift toward persistent colonization or invasive disease. Understanding the complex interactions between A. fumigatus, the host, and other members of the respiratory microbiome is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent and treat Aspergillus-related diseases.

Health Implications

Aspergillus fumigatus has significant implications for human health, primarily as an opportunistic pathogen causing a spectrum of diseases collectively known as aspergillosis:

Invasive Aspergillosis (IA):

- Most severe form of aspergillosis, with mortality rates ranging from 40% to 90%

- Primarily affects severely immunocompromised individuals

- High-risk groups include patients with hematological malignancies, hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplant recipients, and those with prolonged neutropenia

- Characterized by hyphal invasion of blood vessels leading to thrombosis, hemorrhage, and tissue necrosis

- Primarily affects the lungs but can disseminate to other organs including the brain, heart, and kidneys

- Symptoms include fever, chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, and respiratory distress

- Diagnosis challenging due to low sensitivity of culture methods and non-specific clinical presentation

- Treatment typically involves systemic antifungal therapy with voriconazole as first-line treatment

- Early diagnosis and treatment crucial for improved outcomes

- Increasing incidence due to growing population of immunocompromised individuals

Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA):

- Progressive destruction of lung tissue occurring over months to years

- Affects approximately 3 million people worldwide

- Most common in patients with underlying lung diseases such as tuberculosis, COPD, or sarcoidosis

- Characterized by cavity formation, fungal balls, and progressive fibrosis

- Symptoms include weight loss, fatigue, cough, hemoptysis, and shortness of breath

- Estimated 15% mortality within the first 6 months, often due to massive hemoptysis

- Requires long-term (often lifelong) antifungal therapy

- Surgical intervention sometimes necessary for localized disease or complications

- Quality of life significantly impacted by chronic symptoms and treatment side effects

- Often misdiagnosed or diagnosed late in disease course

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA):

- Hypersensitivity reaction to A. fumigatus in the airways

- Primarily affects patients with asthma (1-2% of asthma patients) and cystic fibrosis (7-9% of CF patients)

- Characterized by bronchial inflammation, mucus plugging, and bronchiectasis

- Symptoms include wheezing, coughing, fever, and malaise

- Diagnosis based on clinical, radiological, and immunological criteria

- Treatment involves corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and sometimes antifungal therapy

- Can lead to permanent lung damage if not properly managed

- Recurrent episodes common, requiring long-term management

- Significant impact on quality of life and lung function

- Early diagnosis and treatment may prevent irreversible lung damage

Aspergilloma (Fungal Ball):

- Growth of fungal mycelia within a pre-existing lung cavity

- Most commonly occurs in cavities resulting from tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, or other lung diseases

- May remain stable for years or progress to chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- Symptoms can include cough, hemoptysis (sometimes severe), weight loss, and fatigue

- Diagnosis typically made through characteristic radiographic appearance

- Treatment options include surgical resection for severe hemoptysis or antifungal therapy

- Hemoptysis can be life-threatening in some cases

- Surgical intervention associated with significant morbidity due to underlying lung disease

- Medical management often challenging due to poor drug penetration into the cavity

- Long-term monitoring required due to risk of progression

Aspergillus Sinusitis:

- Ranges from allergic (allergic fungal sinusitis) to invasive forms

- Allergic form similar to ABPA but affecting the sinuses

- Invasive form primarily affects immunocompromised hosts

- Symptoms include nasal congestion, facial pain, headache, and visual disturbances

- Invasive form can extend to the orbit and brain with potentially fatal consequences

- Treatment depends on the form, ranging from surgery and corticosteroids for allergic forms to aggressive antifungal therapy for invasive disease

- Chronic forms may require long-term management

- Recurrence common, particularly in allergic forms

- Diagnosis often delayed due to non-specific symptoms

- Surgical debridement often necessary in addition to antifungal therapy

Emerging At-Risk Populations:

- Increasing recognition of aspergillosis in patients with severe influenza and COVID-19

- Growing concern in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Patients with cystic fibrosis at risk for various forms of aspergillosis

- Individuals with mild immunosuppression due to conditions like diabetes or alcoholism

- Patients receiving novel immunotherapies and targeted therapies

- Increasing incidence in intensive care unit patients without classical risk factors

- Patients with autoimmune diseases on immunomodulatory therapy

- Individuals with genetic susceptibility factors

- Elderly patients with age-related immune dysfunction

- Patients with structural lung abnormalities from various causes

Antifungal Resistance:

- Increasing prevalence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus strains worldwide

- Environmental resistance developing due to agricultural use of azole fungicides

- Patient-acquired resistance developing during long-term antifungal therapy

- Multi-azole resistant strains associated with treatment failure and increased mortality

- Limited alternative treatment options for resistant infections

- Challenges in detection of resistant strains in clinical settings

- Resistance mechanisms include mutations in the cyp51A gene and efflux pump overexpression

- Geographic variations in resistance patterns

- Need for antifungal stewardship to preserve efficacy of available drugs

- Development of new antifungal agents and combination therapies to address resistance

Diagnostic Challenges:

- Low sensitivity of conventional culture methods

- Difficulty in distinguishing colonization from infection

- Non-specific clinical presentation, particularly in early disease

- Limited availability of non-culture-based diagnostic methods in many settings

- Invasive procedures often required for definitive diagnosis

- Radiological findings may be non-specific or atypical

- Biomarkers like galactomannan and β-D-glucan have limitations in certain patient populations

- Molecular methods not standardized or widely available

- Delays in diagnosis contributing to poor outcomes

- Need for improved point-of-care diagnostics

Therapeutic Considerations:

- Limited antifungal drug classes available for treatment

- Significant drug-drug interactions with many antifungals

- Toxicity concerns, particularly with amphotericin B formulations

- Variable drug penetration into different tissues

- Challenges in determining optimal treatment duration

- Need for therapeutic drug monitoring to ensure adequate drug exposure

- Surgical intervention often necessary in certain forms of aspergillosis

- Adjunctive immunotherapy being explored for refractory cases

- Combination antifungal therapy for severe or resistant infections

- Prophylactic strategies for high-risk populations

Public Health Impact:

- Significant economic burden on healthcare systems

- Estimated to cost the US healthcare system $1.2 billion annually

- Global burden of disease not fully quantified

- Limited awareness among healthcare providers

- Lack of surveillance systems for monitoring incidence and resistance

- Environmental factors influencing exposure and disease risk

- Occupational exposures in certain industries increasing risk

- Hospital construction activities associated with outbreaks in high-risk patients

- Need for improved infection control measures in healthcare settings

- Increasing global burden due to growing at-risk populations

The health implications of A. fumigatus are substantial, particularly for vulnerable populations with compromised immunity or underlying respiratory conditions. The spectrum of diseases caused by this fungus ranges from allergic manifestations to life-threatening invasive infections, with significant morbidity and mortality. The emergence of antifungal resistance and the expanding range of at-risk populations present growing challenges for clinical management. Improved diagnostic methods, novel therapeutic approaches, and enhanced surveillance are needed to address the global burden of aspergillosis and improve outcomes for affected individuals.

Metabolic Activities

Aspergillus fumigatus exhibits diverse and adaptable metabolic activities that contribute to its environmental persistence and pathogenicity:

Carbon Metabolism:

- Versatile carbon utilization capabilities, able to metabolize various sugars, alcohols, and organic acids

- Preferentially utilizes glucose through glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

- Capable of utilizing alternative carbon sources such as acetate, ethanol, and fatty acids

- Possesses complete sets of enzymes for glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway

- Adapts carbon metabolism based on nutrient availability in different environments

- During infection, shifts metabolism to utilize host-derived carbon sources

- Acetate utilization particularly important during host colonization and infection

- Carbon catabolite repression regulates preferential use of glucose over other carbon sources

- Glyoxylate cycle allows utilization of two-carbon compounds as carbon sources

- Metabolic flexibility contributes to survival in diverse ecological niches

Nitrogen Metabolism:

- Utilizes various nitrogen sources including ammonium, nitrate, and organic nitrogen compounds

- Possesses nitrate reductase for assimilation of nitrate

- Secretes proteases to break down environmental and host proteins for nitrogen acquisition

- Nitrogen metabolite repression regulates preferential use of ammonium over other nitrogen sources

- Adapts nitrogen metabolism based on availability in different environments

- Amino acid biosynthetic and catabolic pathways well-developed

- Nitrogen acquisition and metabolism crucial for growth in nitrogen-limited host environments

- Produces urease to utilize urea as a nitrogen source

- Nitrogen metabolism linked to secondary metabolite production

- Efficient nitrogen scavenging contributes to survival in nutrient-poor conditions

Lipid Metabolism:

- Produces various lipases and phospholipases for lipid degradation

- Capable of utilizing host lipids as carbon and energy sources during infection

- Synthesizes ergosterol as the primary sterol in cell membranes (target of azole antifungals)

- Produces oxylipins with various biological activities

- Lipid metabolism plays crucial roles in cell membrane integrity and signaling

- Fatty acid synthesis and degradation pathways well-developed

- Lipid droplets serve as energy storage during nutrient limitation

- Membrane lipid composition adapts to environmental conditions

- Phospholipid metabolism important for cell membrane function and virulence

- Lipid metabolism linked to biofilm formation and stress resistance

Secondary Metabolite Production:

- Produces various bioactive secondary metabolites with diverse functions

- Gliotoxin, a potent immunosuppressive compound, inhibits phagocyte function and induces apoptosis

- Fumagillin inhibits angiogenesis and neutrophil function

- Helvolic acid has antibacterial properties

- Fumitremorgins have neurotoxic effects

- Fumigaclavines have various biological activities including vasoconstriction

- Secondary metabolite production regulated by environmental conditions and developmental stage

- Metabolites contribute to competitive fitness in environmental niches

- Many secondary metabolites have immunomodulatory effects

- Secondary metabolite gene clusters often located in subtelomeric regions of chromosomes

- Production often triggered by stress conditions or nutrient limitation

Iron Acquisition and Metabolism:

- Produces siderophores (iron-chelating compounds) for iron acquisition

- Two major siderophores: fusarinine C (extracellular) and ferricrocin (intracellular)

- Iron acquisition crucial for growth in iron-limited host environments

- Siderophore production essential for virulence in animal models

- Reductive iron assimilation as an alternative iron acquisition system

- Iron metabolism tightly regulated to prevent toxicity from excess iron

- Iron availability influences secondary metabolite production

- Siderophore biosynthesis requires specific precursors and enzyme systems

- Iron acquisition systems upregulated during infection

- Competition with host iron-binding proteins during infection

Stress Response Metabolism:

- Produces various stress-protective compounds including trehalose, mannitol, and glycerol

- Trehalose accumulation protects against thermal and oxidative stress

- Antioxidant systems including catalases, superoxide dismutases, and peroxidases

- Thioredoxin and glutathione systems for maintaining redox balance

- Heat shock proteins induced under stress conditions

- Melanin production protects against UV radiation and oxidative stress

- Cell wall remodeling in response to cell wall stress

- Metabolic adaptations to pH stress

- Stress response metabolism crucial for survival in hostile host environments

- Cross-protection between different stress responses

Hypoxia Adaptation:

- Adapts metabolism to low oxygen conditions found in host tissues

- Shifts from aerobic respiration to fermentative metabolism under severe hypoxia

- Upregulates genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis under hypoxia

- Increases cell wall thickness through upregulation of β-glucan synthesis

- Hypoxia adaptation crucial for growth in oxygen-limited infection sites

- Hypoxia-responsive transcription factors regulate metabolic adaptation

- Nitric oxide detoxification systems important under hypoxic conditions

- Hypoxia influences virulence factor expression

- Metabolic flexibility allows growth across oxygen gradients

- Adaptation to hypoxia linked to antifungal drug resistance

pH Adaptation:

- Grows across a wide pH range (3.7-7.6)

- Adapts metabolism to different pH environments

- Produces acids or bases to modify local pH

- pH-responsive gene expression regulated by transcription factor PacC

- Secretes different sets of enzymes depending on ambient pH

- Cell wall composition changes in response to pH

- pH adaptation important for growth in different host niches

- Acid tolerance contributes to survival in certain host environments

- pH influences secondary metabolite production

- Adaptation to alkaline pH involves specific metabolic adjustments

Biofilm Metabolism:

- Forms structured biofilms with distinct metabolic zones

- Extracellular matrix production requires specific metabolic pathways

- Metabolic heterogeneity within biofilm populations

- Altered gene expression compared to planktonic growth

- Increased resistance to antifungal drugs through metabolic adaptations

- Nutrient gradients within biofilms influence local metabolism

- Oxygen limitation in biofilm interior leads to hypoxic adaptation

- Quorum sensing-like mechanisms may coordinate metabolic activities

- Biofilm formation enhances survival in hostile environments

- Metabolic dormancy in biofilm contributes to stress resistance

Interactions with Host Metabolism:

- Competes with host cells for essential nutrients

- Modifies local host environment through secreted metabolites

- Interferes with host immune cell metabolism through immunomodulatory compounds

- Adapts metabolism to utilize host-derived nutrients

- Alters host cell metabolism through various virulence factors

- Metabolic adaptation to host defense mechanisms

- Nutrient acquisition from host tissues through secreted enzymes

- Metabolic flexibility allows adaptation to changing host conditions

- Influences host inflammatory responses through metabolic products

- Competition with other microorganisms for metabolic resources in the host

The metabolic versatility of A. fumigatus is a key factor in its success as both an environmental saprophyte and an opportunistic pathogen. Its ability to adapt metabolism to diverse environmental conditions, utilize various nutrient sources, produce bioactive secondary metabolites, and respond to different stressors enables it to thrive in a wide range of ecological niches, including the human host. Understanding these metabolic activities provides insights into the fungus's pathogenicity and may reveal potential targets for therapeutic intervention. The complex metabolic networks of A. fumigatus represent both a challenge for antifungal development and an opportunity for identifying novel approaches to combat this important pathogen.

Clinical Relevance

Aspergillus fumigatus has significant clinical relevance as the primary causative agent of aspergillosis, a spectrum of diseases with substantial morbidity and mortality:

Invasive Aspergillosis (IA):

- Life-threatening infection with mortality rates of 40-90% depending on patient population

- Primary risk factors include prolonged neutropenia, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, solid organ transplantation, and prolonged corticosteroid therapy

- Typically begins as a pulmonary infection with potential for dissemination to other organs

- Clinical presentation includes fever, cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, and respiratory distress

- Radiographic findings include nodules, often with a "halo sign," cavitation, and consolidation

- Diagnosis challenging, often requiring combination of clinical, radiological, and microbiological criteria

- Galactomannan and β-D-glucan assays used as biomarkers for diagnosis

- First-line treatment is voriconazole, with liposomal amphotericin B and isavuconazole as alternatives

- Surgical resection sometimes necessary for localized disease

- Early diagnosis and treatment crucial for improved outcomes

- Prophylaxis recommended for high-risk patients

Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA):

- Spectrum of chronic lung infections affecting patients with underlying structural lung disease

- Subtypes include chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis, and aspergilloma

- Affects an estimated 3 million people worldwide

- Risk factors include previous pulmonary tuberculosis, COPD, sarcoidosis, and prior pneumothorax

- Symptoms develop over months to years and include weight loss, fatigue, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea

- Radiographic findings include cavitation, fungal balls, and progressive fibrosis

- Diagnosis based on combination of clinical, radiological, and serological criteria

- Treatment typically involves long-term (often lifelong) oral azole therapy

- Surgical resection considered for localized disease or severe hemoptysis

- Progressive disease despite treatment common

- Five-year mortality rate approximately 50%

- Quality of life significantly impacted by chronic symptoms and treatment side effects

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA):

- Hypersensitivity reaction to A. fumigatus colonizing the airways

- Primarily affects patients with asthma (1-2%) and cystic fibrosis (7-9%)

- Characterized by type I (IgE-mediated) and type III (immune complex) hypersensitivity reactions

- Clinical features include wheezing, pulmonary infiltrates, bronchiectasis, and elevated serum IgE

- Diagnostic criteria include asthma, immediate skin reactivity to Aspergillus antigens, elevated total IgE, elevated Aspergillus-specific IgE and IgG, and central bronchiectasis

- Treatment involves corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and sometimes antifungal therapy

- Recurrent exacerbations common, requiring long-term management

- Can lead to permanent lung damage and fibrosis if not properly managed

- Monitoring of total IgE levels useful for assessing treatment response

- Early diagnosis and treatment may prevent irreversible lung damage

Aspergilloma (Fungal Ball):

- Colonization of pre-existing lung cavities by Aspergillus, forming a fungal ball

- Most commonly occurs in cavities resulting from tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, or other lung diseases

- May remain asymptomatic or cause symptoms including cough, hemoptysis, and weight loss

- Hemoptysis can be life-threatening in some cases

- Characteristic radiographic appearance of a mobile intracavitary mass

- Serum Aspergillus precipitins typically positive

- Treatment options include surgical resection for severe hemoptysis or antifungal therapy

- Surgical intervention associated with significant morbidity due to underlying lung disease

- Intracavitary instillation of antifungals sometimes used when surgery not feasible

- Long-term monitoring required due to risk of progression to chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

Emerging Clinical Entities:

- COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) emerging as a significant complication in critically ill COVID-19 patients

- Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) recognized in severe influenza cases

- Increasing recognition of aspergillosis in patients with COPD

- Aspergillus bronchitis in patients with bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis

- Aspergillus sensitization in severe asthma

- Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis following pulmonary COVID-19

- Aspergillosis in patients with novel immunotherapies and targeted therapies

- Aspergillus colonization in lung transplant recipients

- Aspergillosis in patients with autoimmune diseases on immunomodulatory therapy

- Aspergillus infection in critically ill patients without classical risk factors

Diagnostic Approaches:

- Direct microscopy using calcofluor white or KOH preparations

- Culture on specialized media such as Sabouraud dextrose agar

- Histopathological examination showing septate, acute-angle branching hyphae

- Galactomannan detection in serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or other specimens

- β-D-glucan assay as a pan-fungal marker

- PCR-based methods for detection of Aspergillus DNA

- Lateral flow device tests for point-of-care diagnosis

- Radiological imaging including chest X-ray, CT, and sometimes MRI

- Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage for sampling lower respiratory tract

- Aspergillus-specific IgG and IgE for diagnosis of CPA and ABPA

- Therapeutic challenges in distinguishing colonization from infection

- Need for improved diagnostic methods with higher sensitivity and specificity

Therapeutic Management:

- Voriconazole as first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis

- Isavuconazole and liposomal amphotericin B as alternative primary therapies

- Posaconazole and itraconazole for chronic forms and prophylaxis

- Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin) as salvage therapy or in combination

- Combination antifungal therapy for refractory cases

- Therapeutic drug monitoring recommended for azole antifungals

- Surgical intervention for localized disease, severe hemoptysis, or treatment failure

- Corticosteroids for allergic forms to reduce inflammation

- Antifungal prophylaxis for high-risk patients

- Immunomodulatory approaches including interferon-gamma and granulocyte transfusions

- Novel antifungals in development including olorofim, fosmanogepix, and ibrexafungerp

- Challenges in determining optimal treatment duration

- Management of drug-drug interactions, particularly with azoles

- Antifungal stewardship to preserve drug efficacy

Antifungal Resistance:

- Increasing prevalence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus worldwide

- Environmental resistance due to agricultural use of azole fungicides

- Patient-acquired resistance during long-term antifungal therapy

- TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations in the cyp51A gene as common resistance mechanisms

- Multi-azole resistant strains associated with treatment failure and increased mortality

- Limited treatment options for resistant infections

- Challenges in detection of resistant strains in clinical settings

- Geographic variations in resistance patterns

- Need for surveillance programs to monitor resistance trends

- Development of new antifungal classes to address resistance

Special Patient Populations:

- Hematological malignancy patients at high risk during neutropenic periods

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients at risk during pre-engraftment and GVHD

- Solid organ transplant recipients, particularly lung transplant patients

- Patients with chronic granulomatous disease at lifelong risk

- Cystic fibrosis patients at risk for ABPA and other forms

- COPD patients increasingly recognized as at risk for invasive disease

- Critically ill patients in intensive care units

- Patients with COVID-19 and severe influenza

- HIV-infected individuals with advanced disease

- Patients on biological therapies affecting immune function

- Tailored diagnostic and therapeutic approaches needed for different populations

- Prophylaxis strategies differ based on patient risk factors

Prevention Strategies:

- HEPA filtration in hospital rooms for high-risk patients

- Antifungal prophylaxis for selected high-risk populations

- Avoidance of construction areas by immunocompromised patients

- Proper management of hospital construction to minimize spore dispersal

- Monitoring of environmental fungal spore counts in healthcare settings

- Prompt diagnosis and treatment of aspergillosis to prevent progression

- Vaccination approaches under investigation

- Immunotherapeutic strategies to enhance host defense

- Patient education regarding environmental exposures

- Infection control measures during periods of high risk

The clinical relevance of A. fumigatus extends across multiple medical specialties, including infectious diseases, pulmonology, hematology, oncology, transplantation medicine, and critical care. The diverse manifestations of aspergillosis, coupled with diagnostic challenges and increasing antifungal resistance, make this pathogen a significant concern in clinical practice. Advances in diagnostic methods, therapeutic approaches, and prevention strategies are needed to improve outcomes for patients at risk for or affected by Aspergillus-related diseases. The emergence of new at-risk populations and clinical entities highlights the evolving nature of this pathogen's clinical impact and the need for continued vigilance and research.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Aspergillus fumigatus engages in complex interactions with other microorganisms in both environmental and host settings, influencing microbial community dynamics and potentially affecting disease outcomes:

Interactions with Respiratory Bacterial Pathogens:

- Complex relationship with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airways

- P. aeruginosa produces compounds that inhibit A. fumigatus growth and biofilm formation

- A. fumigatus can modify P. aeruginosa virulence factor production

- Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation inhibited by certain A. fumigatus metabolites

- Co-infection with bacterial pathogens often associated with worse clinical outcomes

- Metabolic interactions including competition for essential nutrients

- Altered antibiotic and antifungal susceptibility in polymicrobial settings

- Synergistic effects on host inflammatory responses during co-infection

- Bacterial-fungal interactions influence colonization patterns in chronic lung diseases

- Physical interactions within mixed-species biofilms in the respiratory tract

Interactions with the Respiratory Microbiome:

- A. fumigatus colonization can alter the composition of the respiratory microbiome

- Recent research suggests A. fumigatus can disbalance the lung microbiome, leading to enrichment of anaerobic bacteria

- Commensal bacteria may provide colonization resistance against A. fumigatus

- Antibiotic treatment disrupting the bacterial microbiome may facilitate A. fumigatus colonization

- Microbiome composition may influence susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis

- Metabolic byproducts from commensal bacteria may inhibit or promote A. fumigatus growth

- Respiratory dysbiosis may create conditions favorable for A. fumigatus establishment

- Probiotic approaches being explored to prevent A. fumigatus colonization

- Interactions with the microbiome may influence antifungal drug efficacy

- Microbiome signatures potentially useful as biomarkers for Aspergillus colonization

Interactions with Other Fungi:

- Competition with other Aspergillus species in environmental and clinical settings

- Produces compounds with antifungal activity against competing fungi

- Co-infection with other fungal pathogens such as Candida species occasionally observed

- Competitive interactions for ecological niches in the environment and host

- Potential for horizontal gene transfer between fungal species

- Mixed Aspergillus infections reported in some clinical cases

- Species-specific differences in virulence and antifungal susceptibility

- Interactions with environmental fungi may influence acquisition of antifungal resistance

- Competition with other fungi for limited resources in the host environment

- Potential for synergistic pathogenicity in mixed fungal infections

Interactions with Viruses:

- Increasing recognition of Aspergillus co-infection in severe viral respiratory infections

- COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) emerging as a significant complication

- Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) recognized in severe influenza cases

- Viral damage to respiratory epithelium may facilitate A. fumigatus invasion

- Virus-induced immunosuppression may predispose to invasive aspergillosis

- Viral-fungal co-infections associated with worse clinical outcomes

- Diagnostic challenges in distinguishing viral from fungal pneumonia

- Therapeutic considerations in managing viral-fungal co-infections

- Potential for viral-fungal synergism in pathogenesis

- Mechanistic basis of viral-fungal interactions not fully elucidated

Microbial Antagonism:

- Produces various antimicrobial compounds that inhibit bacterial and fungal competitors

- Gliotoxin has broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity

- Helvolic acid demonstrates antibacterial properties

- Fumagillin inhibits growth of various microorganisms

- Competition for essential nutrients such as iron limits growth of competing microbes

- Acidification of the local environment may inhibit growth of acid-sensitive microorganisms

- Production of hydrolytic enzymes that degrade components of competing microbes

- Biofilm formation provides competitive advantage in polymicrobial communities

- Rapid growth rate allows outcompetition of slower-growing microorganisms

- Antagonistic interactions contribute to microbial community structure in various niches

Microbial Synergism:

- Certain bacterial species may enhance A. fumigatus virulence

- Bacterial degradation of host tissues may facilitate A. fumigatus invasion

- Polymicrobial biofilms may provide enhanced protection against host defenses

- Bacterial suppression of host immunity may promote fungal growth

- Cross-kingdom signaling molecules may coordinate behaviors between species

- Metabolic cooperation through exchange of nutrients and growth factors

- Enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents in polymicrobial settings

- Synergistic effects on host inflammatory responses

- Bacterial production of compounds that promote A. fumigatus germination

- Cooperative degradation of complex substrates in environmental settings

Quorum Sensing and Signaling:

- Produces and responds to various signaling molecules

- Oxylipins function as intra- and inter-species signaling compounds

- May detect and respond to bacterial quorum sensing molecules

- Cell density-dependent regulation of gene expression

- Signaling molecules influence virulence factor production

- Cross-kingdom communication through shared or recognized signals

- Quorum sensing inhibitors as potential therapeutic approach

- Signaling influences biofilm formation and maturation

- Communication within polymicrobial communities coordinates behaviors

- Sensing of host-derived molecules influences microbial interactions

Environmental Interactions:

- Dominant role in decomposition of organic matter in soil and plant debris

- Interactions with soil bacteria and fungi influence nutrient cycling

- Competition with other microorganisms for resources in environmental niches

- Produces enzymes that degrade complex environmental substrates

- Environmental interactions may contribute to acquisition of antifungal resistance

- Adaptation to diverse ecological niches through competitive and cooperative strategies

- Interactions with plant-associated microorganisms

- Role in microbial succession during decomposition processes

- Influence on soil microbial community structure

- Environmental persistence enhanced by interactions with other microorganisms

Therapeutic Implications:

- Polymicrobial nature of infections may influence treatment outcomes

- Need for combination antimicrobial approaches in certain clinical scenarios

- Bacterial-fungal interactions may affect antifungal drug efficacy

- Probiotic approaches being explored to prevent A. fumigatus colonization

- Targeting microbial interactions as novel therapeutic strategy

- Consideration of microbiome effects when administering antibiotics to at-risk patients

- Potential for microbial antagonists as biological control agents

- Diagnostic challenges in polymicrobial infections

- Personalized approaches based on microbiome composition

- Development of narrow-spectrum antimicrobials to preserve beneficial microbiota

Research Challenges and Future Directions:

- Complexity of polymicrobial interactions difficult to model in laboratory settings

- Need for improved in vitro and in vivo models of polymicrobial communities

- Emerging technologies for studying microbial interactions in situ

- Systems biology approaches to understand complex interaction networks

- Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses revealing new insights

- Spatial organization of polymicrobial communities influencing interactions

- Temporal dynamics of microbial interactions during infection progression

- Host factors modulating microbial interactions

- Translation of basic research findings into clinical applications

- Development of microbiome-based biomarkers for risk stratification

The interactions of A. fumigatus with other microorganisms represent a complex and dynamic aspect of its biology, with significant implications for both environmental ecology and human health. These interactions range from antagonistic competition to synergistic cooperation, influencing microbial community structure, pathogenesis, and treatment outcomes. Understanding these complex interactions is crucial for developing more effective approaches to prevent and treat Aspergillus-related diseases, particularly in the context of polymicrobial infections and the growing recognition of the microbiome's role in health and disease. As research in this area continues to advance, new insights into these interactions may lead to novel diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies.

Research Significance

Aspergillus fumigatus holds substantial research significance across multiple scientific disciplines, with implications for basic biology, medicine, ecology, and biotechnology:

Medical Mycology and Infectious Disease Research:

- Model organism for studying opportunistic fungal pathogens

- Insights into mechanisms of fungal pathogenesis and virulence

- Understanding host-pathogen interactions in immunocompromised hosts

- Development and evaluation of antifungal agents

- Investigation of antifungal resistance mechanisms

- Improvement of diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections

- Identification of biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response

- Development of immunotherapeutic approaches for fungal infections

- Understanding the spectrum of Aspergillus-related diseases

- Translational research to improve clinical outcomes

Immunology Research:

- Model for studying innate and adaptive immune responses to fungi

- Investigation of pattern recognition receptors in fungal recognition

- Understanding immunopathology in allergic responses to fungi

- Insights into immune evasion strategies employed by fungal pathogens

- Development of immunomodulatory approaches for fungal diseases

- Study of trained immunity in response to fungal exposure

- Investigation of host genetic factors influencing susceptibility to fungal infections

- Understanding the balance between protective immunity and immunopathology

- Research on immune reconstitution in immunocompromised hosts

- Development of vaccination strategies against fungal pathogens

Molecular and Cellular Biology:

- Model for studying fungal cell biology and development

- Investigation of fungal stress responses and adaptation mechanisms

- Research on eukaryotic gene regulation and expression

- Study of protein secretion and trafficking in filamentous fungi

- Understanding cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling

- Investigation of signal transduction pathways

- Research on fungal morphogenesis and differentiation

- Study of secondary metabolite biosynthesis and regulation

- Understanding mechanisms of antifungal drug action and resistance

- Investigation of fungal biofilm formation and function

Genomics and Systems Biology:

- One of the first filamentous fungi with a sequenced genome

- Model for comparative genomics among pathogenic and non-pathogenic fungi

- Investigation of genome evolution and adaptation

- Study of transcriptional networks and gene regulation

- Proteomics research to understand protein expression patterns

- Metabolomics studies to characterize metabolic profiles

- Systems biology approaches to understand complex biological networks

- Functional genomics to elucidate gene functions

- Epigenetic regulation of gene expression

- Development of computational models of fungal biology

Environmental and Ecological Research:

- Understanding the ecological role of A. fumigatus in natural environments

- Investigation of fungal contributions to nutrient cycling

- Research on fungal adaptation to diverse environmental conditions

- Study of interactions with other microorganisms in environmental settings

- Understanding the emergence of antifungal resistance in environmental isolates

- Investigation of environmental factors influencing fungal growth and dispersal

- Research on fungal responses to climate change

- Study of fungal biodiversity and distribution

- Understanding the impact of human activities on fungal ecology

- Development of environmental monitoring approaches

Biotechnology and Industrial Applications:

- Production of enzymes for industrial applications

- Bioremediation of environmental pollutants

- Production of secondary metabolites with pharmaceutical potential

- Development of fungal expression systems for protein production

- Bioconversion of agricultural and industrial waste

- Production of biofuels and other value-added products

- Improvement of fermentation processes

- Development of fungal-based biosensors

- Exploration of novel bioactive compounds

- Genetic engineering for enhanced production of desired compounds

Microbiome Research:

- Understanding interactions with the human respiratory microbiome

- Investigation of fungal-bacterial interactions in health and disease

- Research on the impact of the microbiome on susceptibility to fungal infections

- Study of polymicrobial biofilms and their clinical significance

- Development of microbiome-based approaches for preventing fungal colonization

- Understanding the role of the mycobiome in human health

- Investigation of cross-kingdom signaling in microbial communities

- Research on the impact of antibiotics on fungal colonization

- Development of probiotic approaches for managing fungal infections

- Study of microbiome signatures as biomarkers for disease risk

Drug Discovery and Development:

- Target identification for novel antifungal agents

- Screening of natural and synthetic compounds for antifungal activity

- Development of new antifungal drug classes

- Investigation of combination therapies for fungal infections

- Repurposing of existing drugs for antifungal applications

- Development of immunomodulatory approaches for fungal diseases

- Research on drug delivery systems for antifungal agents

- Preclinical and clinical evaluation of antifungal candidates

- Development of strategies to overcome antifungal resistance

- Investigation of fungal secondary metabolites as drug leads

Public Health Research:

- Surveillance of aspergillosis incidence and trends

- Monitoring of antifungal resistance patterns

- Investigation of hospital-acquired fungal infections

- Development of infection control strategies

- Research on occupational exposures to Aspergillus

- Economic impact studies of fungal diseases

- Health policy research related to fungal infections

- Investigation of environmental factors influencing exposure risk

- Development of public health interventions for high-risk populations

- Global health aspects of fungal diseases

Emerging Research Areas:

- Investigation of Aspergillus infections in COVID-19 patients

- Research on the impact of climate change on fungal distribution and virulence

- Development of point-of-care diagnostics for resource-limited settings

- Investigation of fungal-viral interactions in the respiratory tract

- Research on the role of extracellular vesicles in fungal pathogenesis

- Development of nanotechnology-based approaches for antifungal therapy

- Investigation of the fungal "exposome" and its health implications

- Research on fungal adaptation to the host environment during chronic infection

- Development of machine learning approaches for predicting disease risk and outcomes

- Investigation of the role of the mycobiome in various human diseases

The research significance of A. fumigatus extends across multiple disciplines and continues to grow as new technologies and approaches enable deeper insights into its biology and clinical impact. As an opportunistic pathogen with increasing clinical importance due to the growing population of immunocompromised individuals, A. fumigatus represents a critical model organism for understanding fungal pathogenesis and developing new approaches to combat fungal diseases. The complex interactions between this fungus, the host, and other microorganisms provide rich opportunities for investigation with potential applications in medicine, biotechnology, and environmental science. Continued research on A. fumigatus is essential for addressing the challenges posed by aspergillosis and other fungal diseases, which represent a significant and often underappreciated global health burden.