Moraxella catarrhalis

Key Characteristics

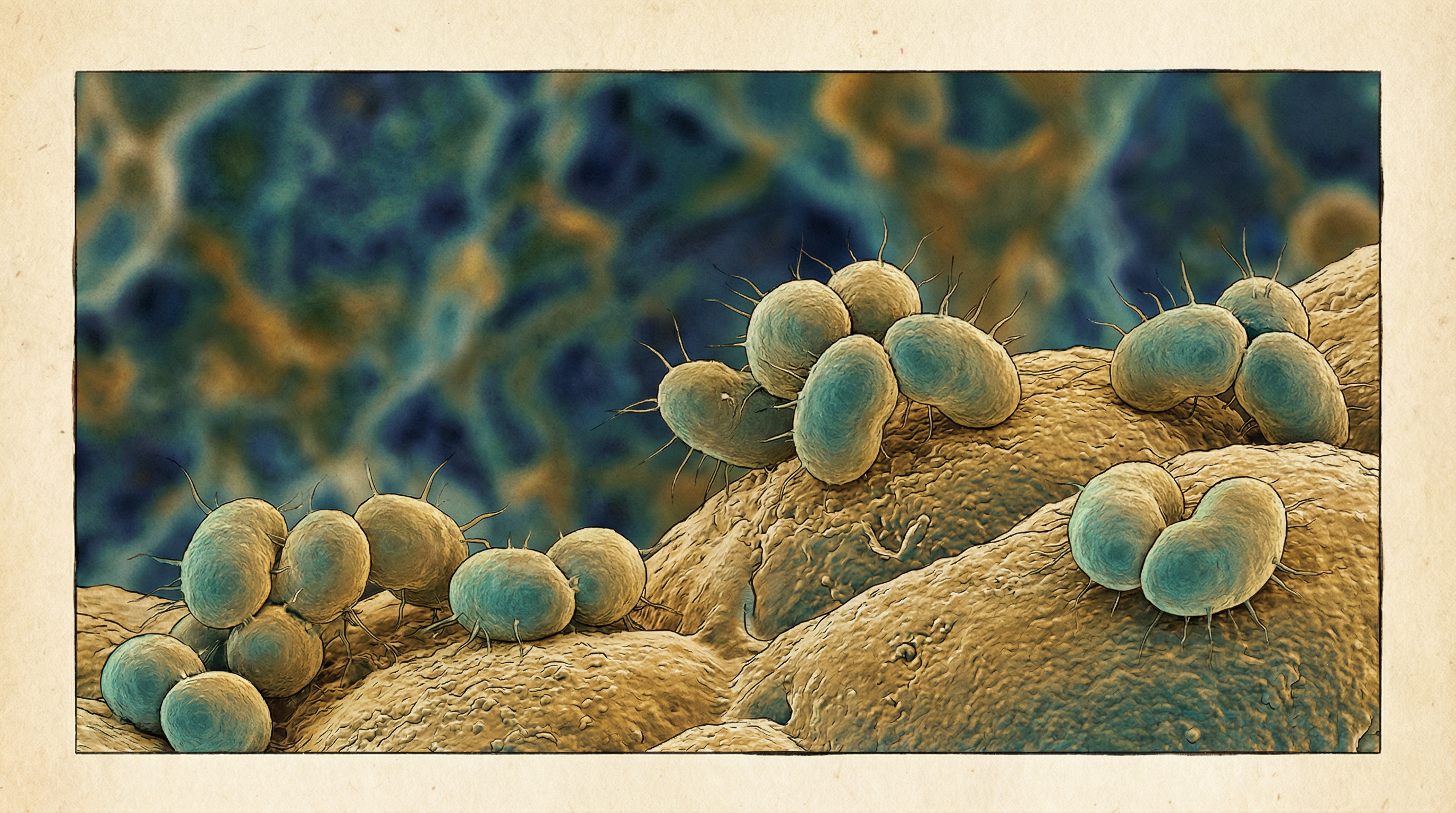

Moraxella catarrhalis is a Gram-negative, aerobic, oxidase-positive, non-motile diplococcus that has emerged as a significant human respiratory pathogen over the past few decades. Previously considered a harmless commensal of the upper respiratory tract, it is now recognized as an important cause of respiratory infections, particularly in children and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Key characteristics of M. catarrhalis include:

- Gram-negative diplococci with flattened adjacent sides, resembling "coffee beans" in appearance

- Unencapsulated bacterium with a cell envelope consisting of an outer membrane, peptidoglycan layer, and inner membrane

- Aerobic, non-fermenting, non-motile organism

- Oxidase-positive and catalase-positive

- DNase-positive, which helps differentiate it from Neisseria species

- Able to reduce nitrate and nitrite

- Grows well on standard laboratory media such as blood agar and chocolate agar

- Forms small, round, opaque, gray-white colonies that can be pushed intact across the agar surface

- Optimal growth temperature of 35-37°C

- Genome size of approximately 1.9-2.0 Mbp with a G+C content of 41-42%

- Taxonomically classified in the family Moraxellaceae, order Pseudomonadales

- Previously known as Branhamella catarrhalis and Neisseria catarrhalis

- Naturally competent for DNA transformation

- Produces β-lactamase in approximately 95% of clinical isolates

- Possesses numerous adhesins and virulence factors, including UspA proteins, MID/Hag, McaP, and OMP CD

- Forms biofilms on biotic and abiotic surfaces

- Lacks flagella but possesses type IV pili that contribute to adherence and natural competence

- Unable to utilize exogenous carbohydrates as carbon sources

- Primarily human-restricted with no known animal reservoir

M. catarrhalis has undergone significant taxonomic reclassification over the years. Originally described as Micrococcus catarrhalis in 1896, it was later renamed Neisseria catarrhalis, then Branhamella catarrhalis, and finally Moraxella catarrhalis in 1984. This reclassification reflects the evolving understanding of its genetic relationship to other bacterial species, particularly its closer relationship to Moraxella species than to Neisseria species.

Role in Human Microbiome

Moraxella catarrhalis primarily colonizes the mucosal surfaces of the human upper respiratory tract, particularly the nasopharynx. Its relationship with the human microbiome can be characterized as follows:

Colonization patterns:

- Frequently colonizes the nasopharynx of young children, with approximately two-thirds of children being colonized within the first year of life

- Colonization rates decrease with age, with only 3-5% of healthy adults carrying M. catarrhalis

- Higher colonization rates (5-32%) are observed in adults with COPD

- Colonization is often transient but can persist for weeks to months

- Seasonal variation in colonization rates, with higher prevalence during winter months

- Multiple strains can colonize simultaneously, particularly in children

Interaction with normal respiratory microbiota:

- Competes with commensal bacteria for nutrients and attachment sites

- Forms part of the complex polymicrobial community in the nasopharynx

- Often co-exists with other respiratory pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae

- May engage in synergistic or antagonistic relationships with other microbiota members

- Biofilm formation facilitates co-existence with other bacterial species

- Horizontal gene transfer occurs between M. catarrhalis and other nasopharyngeal bacteria

Transition from commensal to pathogen:

- Colonization is a prerequisite for infection but does not always lead to disease

- Environmental factors (e.g., viral infections, air pollution) can trigger transition from colonization to infection

- Host factors (e.g., age, immune status, underlying conditions) influence susceptibility to infection

- Bacterial factors (e.g., expression of specific virulence genes) contribute to pathogenicity

- Biofilm formation may represent an intermediate state between commensalism and pathogenicity

Microbiome disruption:

- Antibiotic treatment can disrupt the normal microbiota, potentially allowing for increased M. catarrhalis colonization

- M. catarrhalis β-lactamase production may protect co-colonizing β-lactam-susceptible bacteria from antibiotic effects

- Changes in the respiratory microbiome composition may influence M. catarrhalis behavior and pathogenicity

- Viral respiratory infections can alter the microbiome and facilitate M. catarrhalis overgrowth

Acquisition and transmission:

- Primarily acquired through person-to-person transmission via respiratory droplets

- Daycare attendance is a significant risk factor for colonization in children

- Family members often share the same strain, suggesting household transmission

- No known animal or environmental reservoir

- Nosocomial transmission can occur in healthcare settings

While M. catarrhalis was long considered a harmless commensal, its role as a true pathogen is now well-established. The bacterium exists along a spectrum from asymptomatic colonization to symptomatic infection, with the transition influenced by a complex interplay of bacterial, host, and environmental factors. Understanding its place in the respiratory microbiome is essential for developing strategies to prevent and treat M. catarrhalis infections.

Health Implications

Moraxella catarrhalis has significant health implications as a human respiratory pathogen, causing a spectrum of infections primarily in the upper and lower respiratory tract. The health impact of M. catarrhalis can be characterized as follows:

Otitis media in children:

- Third most common bacterial cause of acute otitis media (AOM) after Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae

- Responsible for approximately 15-20% of AOM cases in children

- Often causes recurrent episodes of otitis media

- Can lead to conductive hearing loss if persistent or recurrent

- May contribute to speech and language development delays in affected children

- Frequently co-exists with other otopathogens in polymicrobial infections

- Biofilm formation in the middle ear contributes to persistence and recurrence

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD):

- Second most common bacterial cause of acute exacerbations of COPD after H. influenzae

- Accounts for 10-15% of COPD exacerbations

- Associated with increased inflammation and worsening of respiratory symptoms

- Contributes to progressive decline in lung function

- Increases healthcare utilization and hospitalization rates

- May persist in the lower airways between exacerbations

- Acquisition of new strains often triggers exacerbations

Other respiratory infections:

- Sinusitis in both children and adults

- Bronchitis in adults

- Community-acquired pneumonia, particularly in elderly and immunocompromised individuals

- Laryngitis and tracheitis

- Occasionally causes bacteremia, especially in immunocompromised hosts

Rare but serious infections:

- Meningitis, particularly in neonates and immunocompromised patients

- Endocarditis

- Septicemia

- Conjunctivitis

- Keratitis

- Wound infections

Risk factors for M. catarrhalis infections:

- Young age (children under 2 years)

- Advanced age (elderly)

- COPD or other chronic respiratory conditions

- Immunocompromised status

- Smoking

- Daycare attendance (for children)

- Winter season

- Recent viral respiratory infection

- Previous antibiotic use

Clinical impact and burden:

- Significant economic burden due to healthcare costs and lost productivity

- Contributes to antibiotic use and potential development of resistance

- Impacts quality of life, particularly in children with recurrent otitis media and adults with COPD

- May require surgical intervention (e.g., tympanostomy tubes) in cases of recurrent otitis media

- Contributes to overall morbidity but rarely causes mortality

- Nosocomial outbreaks have been reported in healthcare settings

Treatment challenges:

- High prevalence of β-lactamase production (>90% of isolates)

- Resistance to penicillins and some cephalosporins

- Increasing resistance to other antibiotic classes

- Biofilm formation contributes to antibiotic tolerance

- Limited treatment options in patients with penicillin allergy

- No currently available vaccine

The health impact of M. catarrhalis is particularly significant in vulnerable populations such as young children, the elderly, and individuals with underlying respiratory conditions. While rarely life-threatening, M. catarrhalis infections contribute substantially to morbidity and healthcare utilization. The increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance in this pathogen further complicates management and underscores the need for effective prevention strategies, including potential vaccine development.

Metabolic Activities

Moraxella catarrhalis exhibits distinctive metabolic characteristics that contribute to its survival in the human respiratory tract and its pathogenicity. Key aspects of M. catarrhalis metabolism include:

Carbon metabolism:

- Notable absence of genes for utilization of exogenous carbohydrates

- Unable to ferment glucose, maltose, sucrose, lactose, or fructose

- Primarily relies on amino acids, fatty acids, and organic acids as carbon sources

- Possesses complete tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for energy generation

- Utilizes the Entner-Doudoroff pathway rather than the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway

- Lacks phosphofructokinase, a key enzyme in glycolysis

- Capable of gluconeogenesis for synthesis of essential carbohydrates

- Metabolizes acetate and other short-chain fatty acids

- Contains genes for metabolism of aromatic compounds

Nitrogen metabolism:

- Possesses nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and nitric oxide reductase

- Can use nitrate as an alternative electron acceptor under oxygen-limited conditions

- Expresses genes for nitrogen metabolism more highly in biofilm growth

- Contains enzymes for ammonia assimilation

- Capable of synthesizing most amino acids except proline and arginine

- Requires exogenous sources of proline and arginine

- Possesses proteases that may contribute to amino acid acquisition from host proteins

Respiration and energy generation:

- Strictly aerobic organism with obligate respiratory metabolism

- Contains a complete electron transport chain

- Possesses cytochrome c oxidase (basis for positive oxidase test)

- Lacks fermentative pathways for anaerobic energy generation

- Upregulates expression of denitrification enzymes in biofilms

- Contains genes for both aerobic and microaerobic respiration

- Adapts to oxygen-limited conditions in the host environment

Iron acquisition and metabolism:

- Requires iron for growth and expresses multiple iron acquisition systems

- Produces transferrin-binding proteins (TbpA and TbpB) to acquire iron from human transferrin

- Contains lactoferrin-binding proteins (LbpA and LbpB) to obtain iron from human lactoferrin

- Possesses heme utilization systems to acquire iron from heme compounds

- Expresses iron-regulated outer membrane proteins

- Contains Fur (ferric uptake regulator) system to regulate iron-responsive genes

- Upregulates iron acquisition systems under iron-limited conditions

Lipid metabolism:

- Synthesizes phospholipids for membrane structure

- Produces lipooligosaccharide (LOS) rather than lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

- LOS lacks O-antigen repeats but contains lipid A and core oligosaccharide

- Modifies LOS structure in response to environmental conditions

- Contains enzymes for fatty acid biosynthesis and β-oxidation

- Produces phospholipases that may contribute to host cell damage

Nucleotide metabolism:

- Contains pathways for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis

- Produces DNase (basis for positive DNase test)

- Naturally competent for DNA uptake and transformation

- May utilize extracellular DNA as a nutrient source

- Incorporates exogenous DNA into its genome through homologous recombination

Stress responses and adaptation:

- Possesses oxidative stress defense mechanisms including catalase and superoxide dismutase

- Adapts metabolism for growth in biofilms

- Modifies gene expression in response to iron limitation

- Contains cold shock and heat shock response systems

- Alters metabolism in response to nutrient limitation

- Expresses genes for resistance to antimicrobial compounds

Metabolic interactions with the host:

- Adapts metabolism to the nutrient-limited environment of the respiratory tract

- Competes with host cells and other bacteria for essential nutrients

- Nitric oxide reductase may protect against host immune defenses

- Metabolic activities contribute to inflammation and tissue damage

- Biofilm formation alters metabolic activity and gene expression

- Metabolic versatility allows adaptation to different host niches

The metabolic capabilities of M. catarrhalis are well-suited to its niche as a human respiratory pathogen. Its inability to utilize carbohydrates distinguishes it from many other bacterial pathogens and reflects its adaptation to the nutrient environment of the respiratory tract. The bacterium's metabolic flexibility, particularly its ability to use alternative electron acceptors and carbon sources, contributes to its survival in diverse conditions within the host, including in biofilms and during infection.

Clinical Relevance

Moraxella catarrhalis has significant clinical relevance as a human respiratory pathogen, with implications for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of infections. Key aspects of its clinical relevance include:

- Diagnostic considerations:

- Laboratory identification:

- Gram stain showing Gram-negative diplococci with flattened adjacent sides

- Growth on standard media (blood agar, chocolate agar) as gray-white, opaque colonies

- Positive oxidase and catalase tests

- Po (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)

- Laboratory identification: