Bacteriophages in the Human Virome

Overview

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that specifically infect bacteria. They represent the most abundant component of the human virome, vastly outnumbering eukaryotic viruses across all body sites. In the human microbiome, bacteriophages play crucial roles in shaping bacterial community composition, facilitating horizontal gene transfer, and potentially influencing human health and disease states. The human body harbors an estimated 35 times more bacteriophages than bacteria, with distinct phage communities existing in different body sites including the gut, oral cavity, skin, and respiratory tract.

Bacteriophages can be broadly categorized based on their life cycles: lytic phages directly kill their bacterial hosts after infection, while temperate phages can either kill their hosts or integrate into bacterial genomes as prophages, potentially conferring new genetic functions to their hosts. This diversity in life cycles contributes to the complex ecological dynamics between phages and bacteria in the human microbiome.

Characteristics

Bacteriophages in the human virome exhibit remarkable diversity in terms of genetic composition, morphology, and host range. The major groups include:

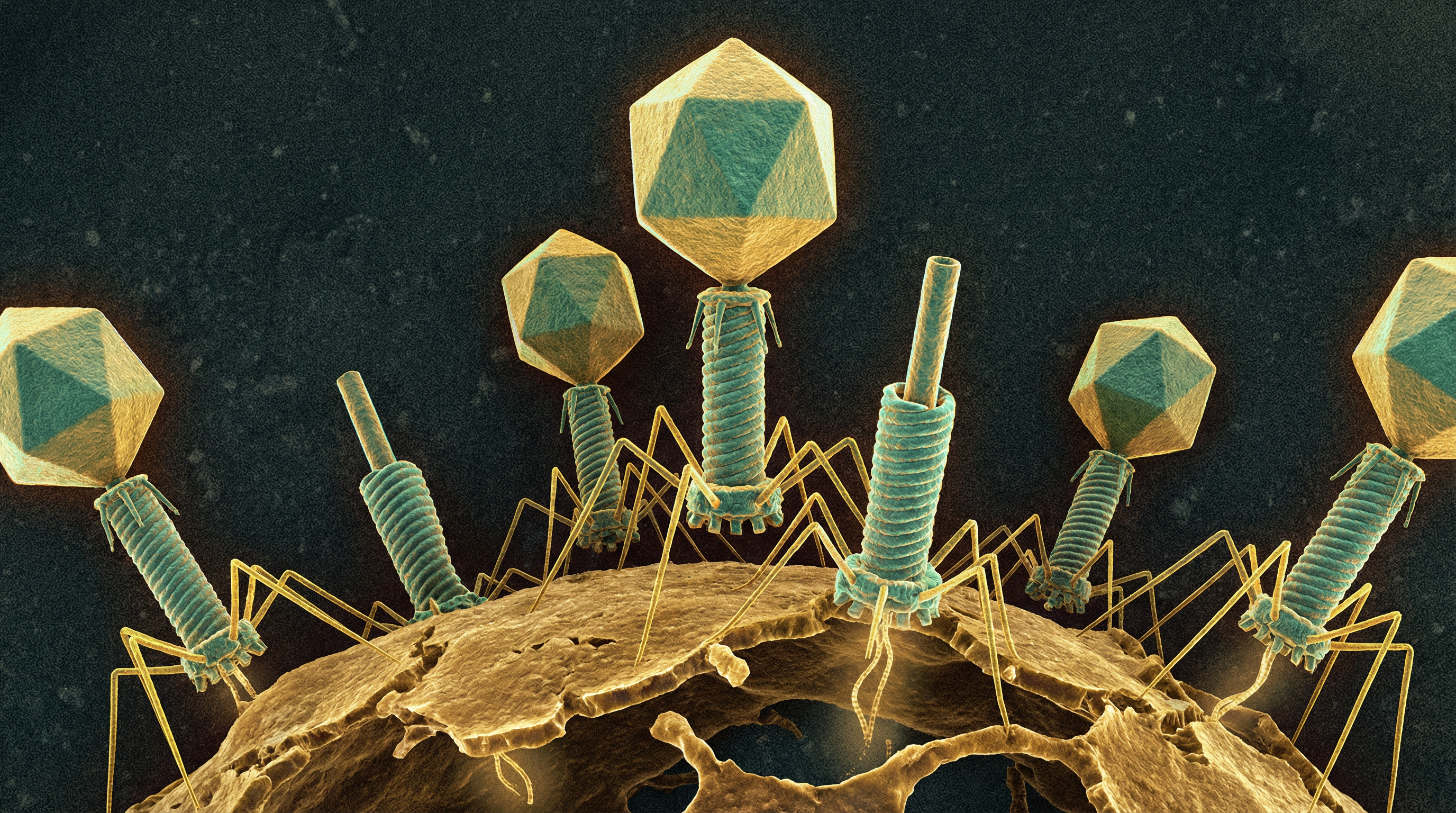

Class Caudoviricetes (formerly order Caudovirales): Tailed double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) phages that represent the most abundant phage type in the human virome. This class includes phages previously classified in the families Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae.

Order Crassvirales: A recently discovered order that includes crAssphage and related phages, which are extremely abundant in the human gut and primarily infect Bacteroides species.

Family Microviridae: Small, icosahedral single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) phages, including ϕX174 and related phages that infect gut bacteria such as E. coli and Bacteroides.

Family Inoviridae: Filamentous ssDNA phages that can establish chronic infections in bacteria, such as Pseudomonas phage Pf and Propionibacterium phages found on skin.

Class Leviviricetes: RNA phages, including those in the family Leviviridae, which are small single-stranded RNA phages that infect gut Enterobacteria.

Morphologically, bacteriophages range from the complex tailed structures of Caudoviricetes to the simple icosahedral capsids of Microviridae and the filamentous structures of Inoviridae. Their genomes can be composed of DNA or RNA, single- or double-stranded, and range in size from a few kilobases to over 200 kilobases.

Role in Human Microbiome

Bacteriophages are integral components of the human microbiome, with distinct phage communities existing in different body sites:

Gut Microbiome

In the gut, bacteriophages are the most abundant viral entities, with crAssphage and other Crassvirales dominating in industrialized populations. The gut virome begins to be established at birth, with mode of delivery (vaginal vs. cesarean) influencing initial phage colonization. Babies born vaginally have more diverse viromes, with Caudoviricetes, Microviridae, and Anelloviridae being the most abundant viruses detected. Breastfeeding further shapes the infant gut virome, with human milk containing numerous bacteriophages that can influence the development of the infant gut microbiome.

The adult gut virome is considered relatively stable and unique to each individual, though it can be modulated by factors such as diet, disease state, and antibiotic use. Bacteriophages in the gut play crucial roles in maintaining bacterial community structure and function, with disruptions in the phage community potentially contributing to gut dysbiosis and associated diseases.

Oral Microbiome

The oral cavity is one of the most densely populated habitats of the human body, containing approximately 6 billion bacteria and potentially 35 times that many viruses, primarily bacteriophages. Studies have shown approximately 10^8 virus-like particles per mL of saliva and 10^7 virus-like particles per milligram of dental plaque.

Oral bacteriophages exhibit biogeographic specificity, with distinct phage communities in saliva compared to sub- and supragingival areas. These phages actively shape the ecology of oral bacterial communities and may be involved in periodontal diseases, as their compositions in the subgingival crevice in moderate to severe periodontitis are significantly altered. However, the extent to which they contribute to dysbiosis or the transition to a disease-promoting state remains unclear.

Skin Microbiome

On the skin, bacteriophages are abundant and diverse, with Staphylococcus phages being among the most prevalent, consistent with the abundance of their bacterial hosts across different microenvironments. The skin phageome varies between body sites and individuals, reflecting differences in skin properties (sebaceous, moist, dry) and host factors.

Recent studies have identified numerous bacteriophages from human skin that infect coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) species, which are among the most abundant colonizers of skin. These phages exhibit genetic diversity and host specificity, with some phage types showing preferential infection of certain Staphylococcus species. The interaction between these phages and their bacterial hosts likely contributes to the formation and temporal stability of skin microbial communities.

Health Implications

Bacteriophages have numerous implications for human health, both directly and indirectly through their interactions with the bacterial microbiome:

Modulation of Bacterial Communities: By selectively infecting and killing specific bacterial species or strains, bacteriophages can shape the composition and diversity of bacterial communities across body sites. This predator-prey relationship contributes to the dynamic equilibrium of the microbiome.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Temperate phages can facilitate horizontal gene transfer between bacteria through transduction, potentially spreading antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors, or metabolic capabilities. This process contributes to bacterial evolution and adaptation within the human microbiome.

Protection Against Pathogens: Some bacteriophages may protect the human host from invading pathogens by binding to and preventing pathogens from crossing mucosal barriers. Additionally, the selective pressure exerted by phages on bacterial populations can limit the dominance of potential pathogens.

Role in Disease States: Alterations in bacteriophage communities have been associated with various disease states. For example, in inflammatory bowel disease, changes in the gut phageome have been observed, though whether these changes are a cause or consequence of disease remains unclear. Similarly, in periodontal disease, the composition of oral phages is significantly altered.

Potential Therapeutic Applications: The specificity of bacteriophages for their bacterial hosts makes them potential therapeutic agents for treating bacterial infections, particularly in the context of increasing antibiotic resistance. Phage therapy has shown promise for treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Metabolic Activities

Bacteriophages influence metabolic activities in the human microbiome through several mechanisms:

Viral Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (vAMGs): Some bacteriophages carry genes that can alter the metabolism of their bacterial hosts. These vAMGs can encode enzymes involved in various metabolic pathways, potentially enhancing bacterial fitness or adapting bacterial metabolism to specific environmental conditions.

Modulation of Bacterial Metabolism: By selectively targeting specific bacterial species or strains, bacteriophages can indirectly influence the metabolic capacity of the entire microbial community. The loss of key metabolic functions due to phage predation can affect the overall metabolic output of the microbiome.

Lysogenic Conversion: Temperate phages that integrate into bacterial genomes as prophages can confer new metabolic capabilities to their hosts. This process, known as lysogenic conversion, can enhance bacterial adaptation to specific niches within the human body.

Influence on Nutrient Cycling: The lysis of bacteria by phages releases cellular contents, including nutrients, into the environment. This "viral shunt" can redistribute nutrients within microbial communities, affecting overall metabolic dynamics.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical relevance of bacteriophages in the human virome encompasses several areas:

Diagnostic Potential: The composition of bacteriophage communities can serve as biomarkers for various health conditions. Changes in the phageome have been associated with diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, periodontal disease, and certain skin disorders.

Phage Therapy: With the rise of antibiotic resistance, bacteriophages are being reconsidered as therapeutic agents for treating bacterial infections. Phage therapy involves the use of lytic phages to selectively target and kill pathogenic bacteria while sparing beneficial microbes.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Transferring the fecal microbiome, including its viruses, from a healthy individual can restore the functionality of the gut and alleviate symptoms of chronic illnesses such as colitis caused by Clostridioides difficile. The role of bacteriophages in the success of FMT is an active area of research.

Antibiotic Resistance: Bacteriophages can contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance genes through transduction. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for addressing the global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Microbiome Modulation: Targeted manipulation of bacteriophage communities represents a potential approach for modulating the microbiome to promote health or treat disease. This concept, sometimes termed "viral therapy," extends beyond traditional phage therapy to include broader ecological interventions.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Bacteriophages engage in complex interactions with other microorganisms in the human microbiome:

Predator-Prey Dynamics: The primary interaction between bacteriophages and bacteria is predatory, with phages infecting and potentially killing their bacterial hosts. This relationship drives coevolutionary dynamics, with both phages and bacteria continually adapting to gain evolutionary advantages.

Bacterial Defense Mechanisms: Bacteria have evolved various defense mechanisms against phage infection, including restriction-modification systems, CRISPR-Cas systems, and surface modifications that prevent phage attachment. These defenses shape the host range of phages and influence community dynamics.

Lysogenic Interactions: Temperate phages can establish long-term relationships with their bacterial hosts through lysogeny. As prophages, they can provide benefits to their hosts, such as immunity against related phages or new metabolic capabilities.

Trans-Kingdom Interactions: Beyond bacteria, bacteriophages may interact with other components of the microbiome, including fungi and eukaryotic viruses. These interactions are less well understood but may contribute to the overall ecology of the microbiome.

Spatial Organization: The spatial distribution of bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts within biofilms and other structured communities influences their interactions. Phages can disrupt biofilms by infecting and lysing bacteria, potentially affecting the stability of these communities.

Research Significance

Bacteriophages in the human virome represent a significant area of research with several key aspects:

Viral Dark Matter: A large percentage of viral sequences in the human virome remain uncharacterized, termed "viral dark matter." This represents a major challenge and opportunity for virologists and bioinformaticians, requiring new approaches to identify and classify novel phages.

Temporal Dynamics: Understanding the temporal stability and fluctuations of bacteriophage communities across different body sites and throughout the human lifespan is crucial for elucidating their roles in health and disease.

Functional Characterization: Beyond taxonomic classification, characterizing the functional roles of bacteriophages in the human microbiome is essential. This includes identifying viral genes that influence bacterial metabolism, virulence, or antibiotic resistance.

Therapeutic Applications: Research on bacteriophages as therapeutic agents continues to advance, with potential applications in treating antibiotic-resistant infections, modulating the microbiome, and developing phage-based diagnostics.

Methodological Advances: Improvements in sequencing technologies, bioinformatic tools, and experimental approaches are enhancing our ability to study bacteriophages in the human virome. These advances include metagenomic approaches, single-cell techniques, and high-throughput screening methods.

In conclusion, bacteriophages constitute a vast and diverse component of the human virome, with profound implications for microbiome ecology, human health, and disease. As research in this field continues to advance, our understanding of these ubiquitous viruses and their roles in the human body will undoubtedly expand, potentially leading to new therapeutic approaches and diagnostic tools.