Overview

Actinomyces israelii is a Gram-positive, filamentous, anaerobic to microaerophilic bacterium that is a natural inhabitant of the human oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and urogenital tract. It is the most prevalent Actinomyces species isolated in human infections, responsible for approximately 70% of orocervicofacial actinomycosis cases.[1]

Key Characteristics

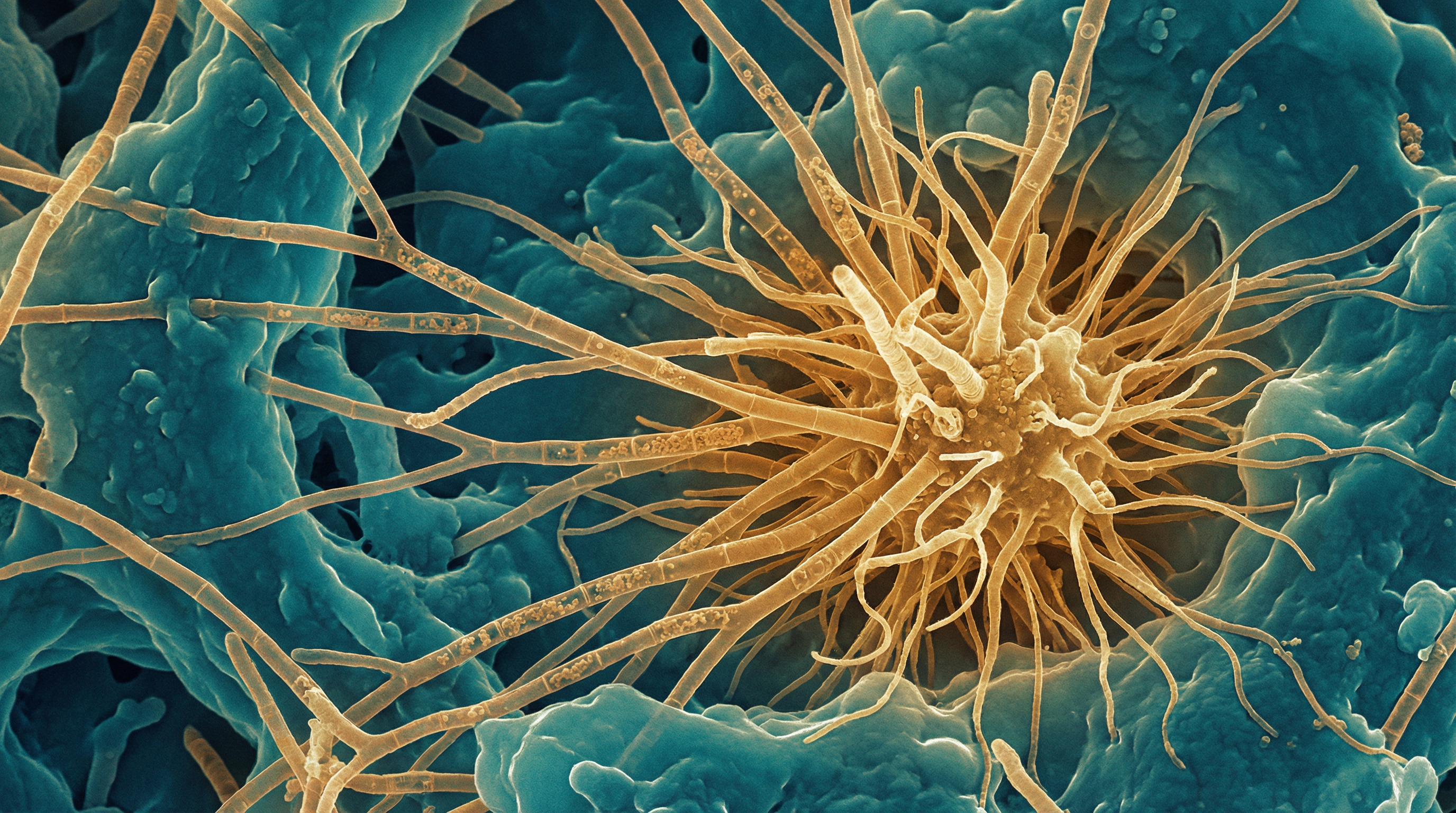

A. israelii is characterized by distinctive features:[2]

- Morphology: Branching, filamentous bacteria with a "molar tooth" colony appearance on agar

- Metabolism: Obligate or facultative anaerobe; slow-growing (5-14 days for colonies)

- Sulfur granules: Forms pathognomonic yellowish granules (40-400 μm) composed of tangled bacterial filaments

- Catalase-negative: Distinguishing biochemical characteristic

- Non-spore-forming, non-motile: Lacks flagella

Role in the Human Microbiome

As a commensal organism, A. israelii colonizes multiple body sites:[3]

Oral Cavity

- Dental plaque and biofilms (supragingival and subgingival)

- Gingival crevices and periodontal pockets

- Tonsillar crypts

- Tongue surface (associated with oral malodor)

Gastrointestinal Tract

- Part of the alimentary tract microbiota

- Can cause abdominal actinomycosis, particularly involving the ileocecal region

Urogenital Tract

- Normal inhabitant of female genital tract

- Colonization promoted by intrauterine device (IUD) use

Biofilm Formation and Bacterial Interactions

A. israelii plays a central role in oral biofilm ecology:[6]

Early Colonization

- Acts as a primary colonizer of tooth surfaces

- Provides attachment sites for secondary colonizers through coaggregation

Coaggregation Partners

- Streptococcus oralis and S. gordonii: Type 2 fimbriae recognize streptococcal receptor polysaccharides (RPS)

- Fusobacterium nucleatum: Acts as a bridging organism connecting early and late colonizers

- Prevotella loescheii: Serves as coaggregation bridge between A. israelii and other species

- Veillonella and Campylobacter gracilis: Significant coaggregation partners in root caries

IUD Biofilm Formation

In vitro studies demonstrate A. israelii can form spider-like colonies and porous biofilm structures on copper IUD surfaces, attaching via extracellular polymer production.[5]

Pathogenesis of Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis occurs when mucosal barriers are breached:[2]

Predisposing Factors

- Trauma (dental procedures, surgery, injury)

- Poor oral hygiene

- Foreign bodies (IUDs, dental implants)

- Immunosuppression

- Chronic inflammation

- Tissue devitalization

Disease Mechanism

- Bacteria gain access to deeper tissues through mucosal disruption

- Form dense masses of interlinked branched filaments that inhibit phagocytic clearance

- Produce proteolytic enzymes enabling tissue invasion

- Create abscesses with characteristic sulfur granules

- Spread contiguously across tissue planes (not lymphatically)

Clinical Forms

| Form | Frequency | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cervicofacial | 50-65% | "Lumpy jaw"; mandible, cheeks, chin involvement |

| Thoracic | 15-30% | Following aspiration; pulmonary involvement |

| Abdominopelvic | 20-32% | IUD-associated; ileocecal predilection |

| CNS | 2-4% | Brain abscesses most common |

IUD-Associated Pelvic Actinomycosis

A well-documented association exists between IUD use and pelvic actinomycosis:[4]

- Colonization rate: 7% of IUD users have Actinomyces-like organisms on Pap smear (range 1.6-44%)

- Risk factors: Prolonged IUD use (>5 years); chronic endometrial inflammation

- Presentation: Pelvic abscesses, tubo-ovarian involvement, peritonitis

- Prevention: IUD replacement every 5 years recommended

Diagnosis

Gold Standards

- Culture: Slow-growing; requires anaerobic conditions; negative in 76% of cases

- Histopathology: Sulfur granules with Gram-positive branching filaments

- Molecular: 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species identification

Emerging Methods

- MALDI-TOF MS (limited accuracy for A. israelii)

- PCR-based detection

- ARDRA (Amplified 16S rDNA Restriction Analysis)

Treatment

A. israelii infections require prolonged antibiotic therapy:[2]

First-Line Treatment

- Intravenous: Penicillin G 12-24 million units/day for 2-6 weeks

- Oral maintenance: Penicillin V or amoxicillin for 6-12 months

Alternative Agents (Penicillin Allergy)

- Ceftriaxone

- Doxycycline

- Clindamycin

- Erythromycin

Key Considerations

- Intrinsically resistant to metronidazole

- Surgical debridement often required

- Combined medical-surgical cure rate >90%

- Recent evidence suggests some patients cured with <6 months therapy

References

Könönen E, Wade WG. Actinomyces and Related Organisms in Human Infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2015;28(2):419-442. doi:10.1128/CMR.00100-14

Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2014;7:183-197. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39601

Li J, Li Y, Zhou Y, et al. Actinomyces and Alimentary Tract Diseases: A Review of Its Biological Functions and Pathology. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:3820215. doi:10.1155/2018/3820215

Gajdács M, Urban E. The Pathogenic Role of Actinomyces spp. and Related Organisms in Genitourinary Infections. Antibiotics. 2020;9(8):524. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9080524

Carrillo M, Valdez B, Vargas L, et al. In vitro Actinomyces israelii biofilm development on IUD copper surfaces. Contraception. 2010;81(3):261-264. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.008

Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, et al. Communication among Oral Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2002;66(3):486-505. doi:10.1128/mmbr.66.3.486-505.2002

Bonnefond S, Catroux M, Melenotte C, et al. Clinical features of actinomycosis: A retrospective, multicenter study of 28 cases. Medicine. 2016;95(24):e3923. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003923

Heo SH, Shin SS, Kim JW, et al. Imaging of Actinomycosis in Various Organs: CT and MR Imaging Findings. RadioGraphics. 2014;34(1):19-33. doi:10.1148/rg.341135077