Candida glabrata

Overview

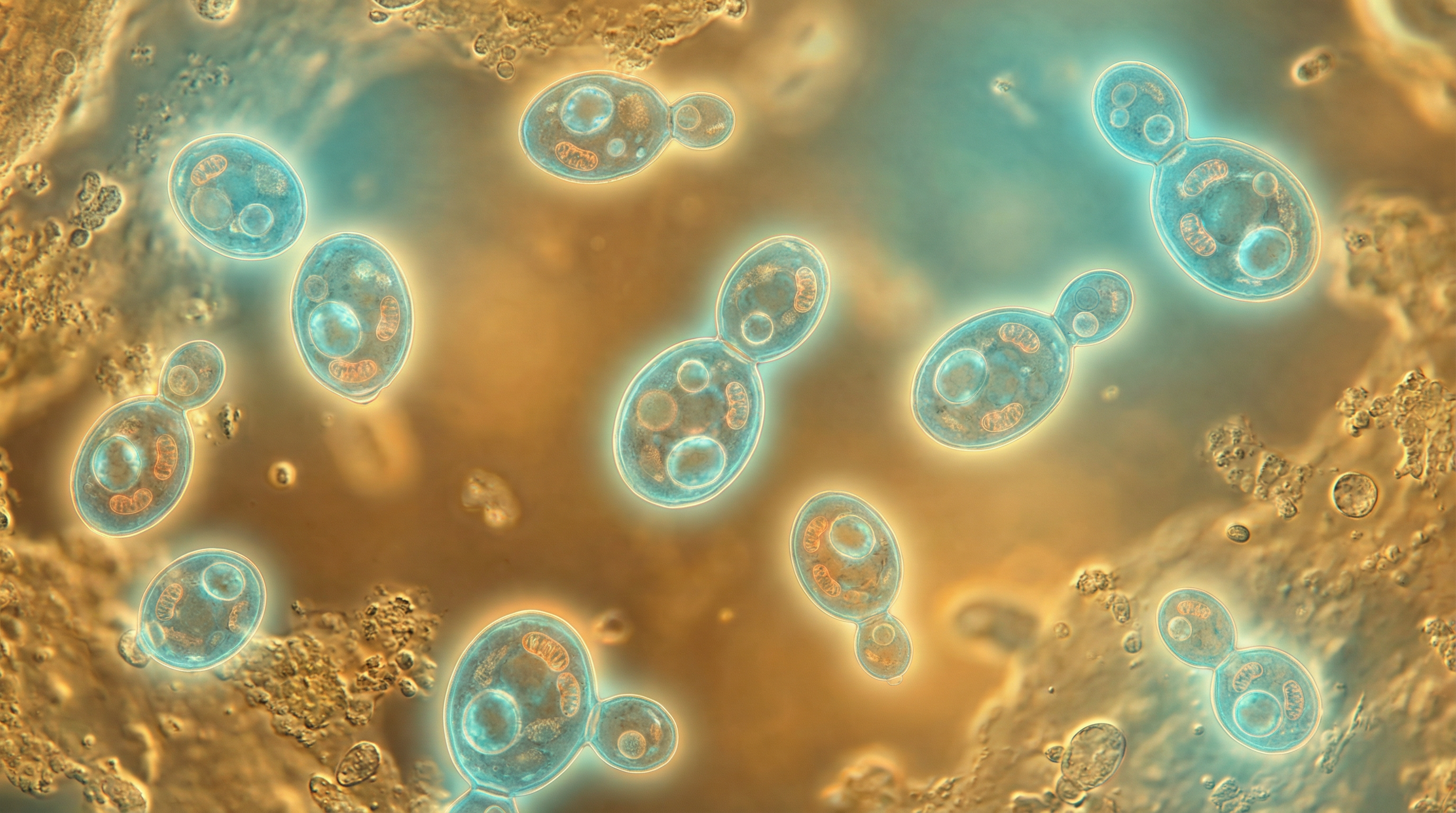

Candida glabrata is a haploid, non-dimorphic yeast that has emerged as a significant opportunistic fungal pathogen in humans. Historically considered a relatively nonpathogenic commensal organism of human mucosal tissues, C. glabrata has gained increasing medical relevance over the past few decades. It is now recognized as the second most common cause of candidiasis after Candida albicans, accounting for approximately 15-25% of invasive clinical cases, particularly in critically ill patients.

Unlike C. albicans, C. glabrata does not form pseudohyphae or true hyphae at temperatures above 37°C, existing exclusively as small blastoconidia (1-4 μm) under all environmental conditions. This morphological limitation, however, has not hindered its pathogenic potential. C. glabrata naturally colonizes various body sites including the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, vaginal tract, and skin of healthy individuals without causing disease. The transition from commensal to pathogen typically occurs in the context of host immune dysfunction, disruption of normal microbiota, or breach of anatomical barriers.

C. glabrata was formerly classified in the genus Torulopsis (as Torulopsis glabrata) due to its lack of pseudohyphae formation but was reclassified to the Candida genus in 1978. Interestingly, despite its name and clinical grouping with other Candida species, phylogenetic analysis reveals that C. glabrata is genetically more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae than to C. albicans. It belongs to the clade Nakaseomyces and has recently been renamed Nakaseomyces glabratus in some taxonomic classifications, though Candida glabrata remains the commonly used clinical designation.

A major clinical concern with C. glabrata infections is their innate resistance to azole antifungal agents, particularly fluconazole, which are commonly used to treat infections caused by other Candida species. This intrinsic resistance, combined with the increasing prevalence of C. glabrata in healthcare settings, presents significant therapeutic challenges. Infections range from superficial mucosal candidiasis to life-threatening invasive disease, with mortality rates for invasive C. glabrata infections approaching 40-60% in some patient populations.

The rising incidence of C. glabrata infections has been attributed to several factors, including the increased use of immunosuppressive therapies, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and indwelling medical devices. Additionally, the aging population and the growing number of individuals with compromised immunity due to conditions such as AIDS, cancer, and diabetes have contributed to the emergence of C. glabrata as a significant human pathogen.

Characteristics

Candida glabrata possesses several distinctive characteristics that differentiate it from other Candida species and contribute to its unique ecological niche and pathogenic potential:

Morphological Features:

- Exists exclusively as small oval blastoconidia (1-4 μm), significantly smaller than C. albicans cells (4-6 μm)

- Lacks the ability to form pseudohyphae or true hyphae at temperatures above 37°C

- Forms smooth, cream-colored, glistening colonies on Sabouraud dextrose agar

- Produces pink to purple colonies on CHROMagar, distinguishing it from C. albicans (green to blue-green)

- Incapable of forming chlamydospores, unlike C. albicans

Genetic and Genomic Properties:

- Possesses a haploid genome, in contrast to the diploid genome of C. albicans

- Genome size of approximately 12.3 megabases with 13 chromosomes

- Contains approximately 5,300 protein-coding genes

- Phylogenetically more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae than to other Candida species

- Demonstrates significant genomic plasticity, with frequent chromosomal rearrangements

- Exhibits electrophoretic karyotype patterns with 10-13 bands, with over 70 different strain types identified

Metabolic Capabilities:

- Limited sugar utilization profile, fermenting and assimilating only glucose and trehalose

- This restricted sugar metabolism is used diagnostically to differentiate C. glabrata from other Candida species

- Capable of growth under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions

- Exhibits metabolic flexibility that allows adaptation to nutrient-limited environments

- Possesses efficient nutrient acquisition systems, particularly for essential micronutrients like iron

Growth Requirements:

- Optimal growth temperature around 37°C

- Tolerates a wide pH range (2-10), with optimal growth at pH 5-6

- Capable of growth in high-osmolarity environments

- Demonstrates remarkable stress tolerance, including resistance to oxidative, osmotic, and thermal stress

- Rapid growth rate with the ability to form colonies after overnight incubation

Cell Wall Composition:

- Cell wall rich in mannoproteins, β-1,3-glucans, and β-1,6-glucans

- Contains less chitin compared to C. albicans

- Surface decorated with various adhesins that facilitate attachment to host surfaces

- Cell wall composition changes in response to environmental stressors

- Modifications in cell wall structure contribute to antifungal resistance

Virulence Factors:

- Expresses multiple adhesins (Epa family) that mediate adherence to host tissues

- Produces hydrolytic enzymes including phospholipases, proteases, and hemolysins

- Forms robust biofilms on both biotic and abiotic surfaces

- Exhibits phenotypic switching, contributing to adaptation and immune evasion

- Possesses mechanisms for evading host immune responses

- Demonstrates remarkable ability to persist and survive inside host immune cells

Antifungal Susceptibility:

- Intrinsic resistance to azole antifungals, particularly fluconazole

- Reduced susceptibility to echinocandins compared to C. albicans

- Susceptible to amphotericin B and flucytosine

- Rapidly develops resistance to multiple antifungal classes

- Biofilm formation significantly increases resistance to antifungal agents

- Possesses multiple drug efflux pumps that contribute to antifungal resistance

Ecological Distribution:

- Primarily associated with humans and other warm-blooded animals

- Common commensal of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, vaginal tract, and skin

- Found in approximately 15-20% of healthy individuals

- Environmental reservoirs include flowers, leaves, water, and soil

- Frequently isolated from hospital environments

- Particularly prevalent in elderly populations

These characteristics collectively enable C. glabrata to successfully colonize various human body sites, adapt to changing environmental conditions, evade host defenses, and cause opportunistic infections when host defenses are compromised. The combination of intrinsic antifungal resistance, robust stress responses, and various virulence factors makes C. glabrata a formidable pathogen despite its inability to form hyphal structures, which are considered important virulence determinants in other Candida species.

Role in Human Microbiome

Candida glabrata occupies a distinct niche within the human microbiome, with complex interactions that influence both host health and microbial community dynamics:

Distribution and Prevalence:

- Present as a commensal in approximately 15-20% of healthy individuals

- Colonizes multiple body sites including the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, vaginal tract, and skin

- Generally maintained at low levels in healthy individuals due to competition with bacteria and host immune surveillance

- More commonly isolated from elderly individuals compared to younger populations

- Prevalence increases in hospitalized patients and those with underlying medical conditions

- Often co-exists with other Candida species, particularly C. albicans

Ecological Niche:

- Primarily occupies mucosal surfaces as part of the normal microbiota

- In the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly found in the lower intestine

- Forms part of the "mycobiome," the fungal component of the human microbiome

- Population density varies by body site, with highest numbers typically in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract

- Colonization patterns influenced by host factors, diet, and antibiotic use

- Capable of long-term persistence in the same host

Interactions with Bacterial Microbiota:

- Engages in complex relationships with bacterial community members

- Competition with bacteria for nutrients and attachment sites helps maintain fungal homeostasis

- Certain bacteria (e.g., lactobacilli) inhibit C. glabrata growth through production of organic acids and antimicrobial compounds

- Antibiotic treatment disrupts bacterial communities, often leading to C. glabrata overgrowth

- C. glabrata can influence bacterial community composition through competition and metabolic interactions

- Forms mixed-species biofilms with various bacterial species, particularly in the oral cavity

Metabolic Contributions:

- Limited direct metabolic contributions to the host due to restricted metabolic capabilities

- May participate in carbohydrate metabolism within the gut ecosystem

- Capable of utilizing byproducts of bacterial metabolism

- Adapts its metabolism based on available nutrients in different body sites

- May compete with beneficial microbes for essential nutrients

- Metabolic activities can influence local microenvironments (e.g., pH, oxygen levels)

Biofilm Formation:

- Forms single-species and mixed-species biofilms on mucosal surfaces

- Biofilm formation contributes to stable colonization and persistence

- Biofilms provide protection against host defenses and antimicrobial agents

- Mixed fungal-bacterial biofilms can exhibit enhanced resistance properties

- Biofilm architecture creates microenvironments that support diverse microbial populations

- Particularly relevant in the oral cavity and on indwelling medical devices

Host-Microbe Interactions:

- Recognized by the host immune system but typically tolerated as a commensal

- Induces less robust inflammatory responses compared to C. albicans

- Maintains a balance with host defenses that allows persistent colonization without disease

- Interacts with host epithelial cells through various adhesins

- May modulate local immune responses, potentially affecting responses to other microorganisms

- Capable of intracellular survival within host immune cells

Response to Environmental Changes:

- Population levels fluctuate in response to diet, host factors, and changes in bacterial communities

- Increases in abundance following antibiotic treatment due to reduced bacterial competition

- Responds to changes in host hormone levels, particularly in the vaginal environment

- Adapts to variations in pH, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability across different body sites

- Demonstrates remarkable resilience to environmental stressors

- Often returns to baseline levels after temporary perturbations in healthy individuals

Dysbiosis and Disease Association:

- Disruption of normal fungal-bacterial balance can lead to C. glabrata overgrowth

- Fungal dysbiosis may contribute to inflammatory conditions and altered immune responses

- Changes in C. glabrata abundance have been associated with various gastrointestinal disorders

- Shifts in the mycobiome may influence bacterial dysbiosis and vice versa

- Restoration of normal microbial communities can help resolve C. glabrata overgrowth

- Emerging evidence suggests potential roles in various chronic conditions

The role of C. glabrata in the human microbiome represents a delicate balance between commensalism and potential pathogenicity. As a member of the normal microbiota, C. glabrata typically exists in harmony with the host and other microorganisms. However, perturbations in this balance, particularly those affecting host immunity or bacterial communities, can lead to C. glabrata overgrowth and potential pathogenicity. Understanding the factors that govern this balance is crucial for developing strategies to maintain healthy microbial communities and prevent C. glabrata-associated diseases.

Health Implications

Candida glabrata has significant health implications that range from asymptomatic colonization to life-threatening invasive disease:

Commensal Relationship:

- In healthy individuals, C. glabrata exists as a harmless commensal on mucosal surfaces

- Asymptomatic colonization is common, with approximately 15-20% of healthy individuals carrying the organism

- The balance between commensalism and pathogenicity is maintained by intact host defenses and normal microbiota

- This balanced relationship persists as long as host immunity remains intact and microbial communities remain stable

- Commensal colonization may provide colonization resistance against more virulent pathogens

- Long-term carriage without symptoms is common in many individuals

Mucosal Infections:

- Oropharyngeal Candidiasis: Less common than C. albicans-associated thrush, but increasing in prevalence

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Accounts for approximately 15% of cases, often with less pronounced symptoms than C. albicans

- Esophageal Candidiasis: Particularly in immunocompromised patients, often with subtle clinical presentation

- Urinary Tract Infections: More common with C. glabrata than other Candida species, especially in catheterized patients

- Mucosal infections typically occur when local defenses are compromised or microbial communities are disrupted

- Often more difficult to treat than C. albicans infections due to intrinsic azole resistance

Invasive Infections:

- Candidemia: Second most common cause after C. albicans, with mortality rates of 40-60%

- Intra-abdominal Candidiasis: Common following gastrointestinal surgery or perforation

- Urinary Candidiasis: Particularly in patients with indwelling urinary catheters

- Endocarditis: Rare but serious infection of heart valves with high mortality

- Meningitis: Uncommon but severe manifestation, particularly in neurosurgical patients

- Invasive infections typically occur in severely immunocompromised patients or those with multiple risk factors

- Often associated with healthcare settings and considered nosocomial infections

Risk Factors for Infection:

- Advanced Age: Significantly higher prevalence in elderly populations

- Immunosuppression: HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, chemotherapy, corticosteroid use

- Diabetes Mellitus: Elevated blood glucose creates favorable conditions for fungal growth

- Broad-spectrum Antibiotic Use: Disrupts protective bacterial communities

- Medical Devices: Central venous catheters, urinary catheters, prosthetic devices

- Gastrointestinal Surgery: Disrupts anatomical barriers and normal microbiota

- Prolonged Hospitalization: Exposure to healthcare-associated strains and multiple interventions

- Parenteral Nutrition: Alters gut microbiota and provides rich nutrient source

Clinical Manifestations:

- Often presents with subtle or nonspecific symptoms compared to C. albicans infections

- Fever and sepsis in candidemia without obvious source of infection

- Mucosal infections may present with less inflammation and erythema than C. albicans

- Urinary tract infections may be asymptomatic or present with typical UTI symptoms

- Invasive disease can affect virtually any organ system

- Clinical presentation often complicated by underlying conditions

- Diagnosis frequently delayed due to subtle presentation and diagnostic challenges

Diagnostic Challenges:

- Small cell size makes microscopic identification more difficult

- Traditional culture methods may take 24-72 hours for definitive identification

- Blood cultures have limited sensitivity (approximately 50%) for invasive candidiasis

- Non-culture diagnostics (β-D-glucan, mannan, PCR) have variable sensitivity and specificity

- Distinguishing colonization from infection can be challenging

- Antifungal susceptibility testing increasingly important due to resistance patterns

- Molecular methods improving speed and accuracy of identification

Treatment Challenges:

- Intrinsic Azole Resistance: Particularly to fluconazole, limiting first-line treatment options

- Emerging Echinocandin Resistance: Particularly concerning as echinocandins are often the treatment of choice

- Biofilm Formation: Significantly increases resistance to most antifungal agents

- Limited Penetration: Some antifungals have poor penetration into certain body sites

- Drug Interactions: Particularly relevant in patients on multiple medications

- Toxicity Concerns: Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity limits use in vulnerable patients

- Limited Antifungal Arsenal: Few drug classes available compared to antibacterial agents

- Treatment often requires combination therapy or alternative approaches

Public Health Impact:

- Increasing prevalence in healthcare settings worldwide

- Significant economic burden due to prolonged hospitalization and expensive treatments

- High mortality rates for invasive disease despite appropriate therapy

- Emerging resistance threatens limited available treatment options

- Particular concern in intensive care units and immunocompromised patient populations

- Growing recognition as a significant healthcare-associated pathogen

- Increasing focus on infection prevention and antifungal stewardship

The health implications of C. glabrata highlight its emergence as a significant opportunistic pathogen, particularly in healthcare settings and vulnerable populations. The combination of intrinsic antifungal resistance, subtle clinical presentation, and increasing prevalence makes C. glabrata infections particularly challenging to diagnose and treat. As the population of immunocompromised individuals continues to grow and antifungal resistance increases, the clinical importance of C. glabrata is likely to continue rising. This underscores the need for improved diagnostic methods, novel antifungal agents, and effective infection prevention strategies to address the growing threat posed by this opportunistic fungal pathogen.

Metabolic Activities

Candida glabrata exhibits distinctive metabolic capabilities that enable its adaptation to various host environments and contribute to its pathogenic potential:

Carbon Metabolism:

- Highly restricted sugar utilization profile compared to other Candida species

- Primarily ferments and assimilates glucose and trehalose only

- Limited ability to use alternative carbon sources such as galactose, sucrose, or maltose

- Efficient glucose sensing and uptake mechanisms

- Possesses multiple hexose transporters with varying affinities

- Capable of both fermentative and respiratory metabolism depending on oxygen availability

- Metabolic flexibility allows adaptation to nutrient-limited environments

- Glucose repression pathways regulate alternative carbon source utilization

Nitrogen Metabolism:

- Utilizes various nitrogen sources including ammonium and amino acids

- Possesses efficient nitrogen scavenging mechanisms

- Expresses proteases that can degrade host proteins to release amino acids

- Nitrogen catabolite repression regulates utilization of non-preferred nitrogen sources

- Amino acid permeases facilitate uptake of host-derived amino acids

- Capable of synthesizing most amino acids when environmental sources are limited

- Nitrogen metabolism linked to stress responses and virulence

- Adapts nitrogen acquisition strategies based on host environment

Lipid Metabolism:

- Synthesizes ergosterol as the major sterol in cell membranes

- Ergosterol biosynthesis is the target of azole antifungals

- Modifications in sterol metabolism contribute to azole resistance

- Produces phospholipases that can degrade host cell membranes

- Capable of utilizing exogenous fatty acids

- Lipid metabolism influences membrane fluidity and permeability

- Adapts membrane composition in response to environmental stressors

- Lipid droplets serve as energy reserves during nutrient limitation

Stress Response Metabolism:

- Robust oxidative stress response systems including catalases and superoxide dismutases

- Efficient production of stress protectants such as trehalose and glycerol

- Metabolic adaptations to survive phagocytosis by immune cells

- Upregulation of chaperones and heat shock proteins under stress conditions

- Remarkable ability to survive in nutrient-poor environments

- Metabolic flexibility enables adaptation to pH fluctuations

- Stress response pathways integrated with core metabolic networks

- Metabolic adaptations contribute to antifungal resistance

Biofilm Metabolism:

- Distinct metabolic profile in biofilm versus planktonic growth

- Reduced metabolic activity in mature biofilms contributes to antifungal resistance

- Extracellular matrix production requires specific metabolic pathways

- Metabolic heterogeneity within biofilm structures

- Adaptation to hypoxic conditions within biofilm environment

- Altered carbon flux during biofilm formation and maturation

- Quorum sensing molecules influence biofilm metabolic activity

- Biofilm dispersal triggered by metabolic cues

Micronutrient Acquisition:

- Sophisticated iron acquisition systems including siderophore utilization

- Efficient copper and zinc uptake mechanisms

- Micronutrient acquisition linked to virulence and stress resistance

- Competition with host and other microbes for essential trace elements

- Metal-responsive transcription factors regulate acquisition systems

- Adaptation to metal-limited environments in the host

- Metal homeostasis crucial for enzyme function and stress resistance

- Detoxification systems for excess metal ions

Metabolic Interactions with Host and Microbiota:

- Competition with gut bacteria for limited nutrients

- Adaptation to nutrient availability in different host niches

- Metabolic responses to host-derived antimicrobial compounds

- Potential metabolic cross-feeding with specific bacterial species

- Metabolic activities can influence local microenvironments

- Adaptation to varying oxygen levels across different body sites

- Metabolic flexibility enables survival in diverse host environments

- Nutrient acquisition from host tissues during infection

Metabolic Basis of Pathogenicity:

- Metabolic adaptation to intracellular environment within phagocytes

- Nutrient acquisition systems upregulated during infection

- Metabolic flexibility contributes to survival in diverse host niches

- Stress response metabolism enables persistence during host defense encounters

- Metabolic adaptations to antifungal exposure

- Energy metabolism shifts during transition from colonization to invasion

- Metabolic pathways linked to adhesin expression and biofilm formation

- Nutrient sensing pathways regulate virulence factor expression

The metabolic capabilities of C. glabrata, particularly its remarkable adaptability to changing environmental conditions and nutrient availability, are central to its success as both a commensal organism and an opportunistic pathogen. Despite having a more restricted carbon utilization profile compared to other Candida species, C. glabrata compensates with highly efficient nutrient acquisition systems and robust stress response mechanisms. These metabolic adaptations enable C. glabrata to persist in diverse host environments, compete with other microorganisms, evade host defenses, and cause opportunistic infections when conditions are favorable. Understanding the metabolic activities of C. glabrata provides insights into its ecological niche within the human microbiome and may reveal potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Clinical Relevance

Candida glabrata has significant clinical relevance across multiple medical specialties due to its increasing prevalence, intrinsic antifungal resistance, and association with high morbidity and mortality:

Epidemiological Trends:

- Second most common cause of candidiasis in many regions, accounting for 15-25% of cases

- Increasing prevalence over the past three decades, particularly in healthcare settings

- Geographical variations in prevalence, with higher rates in North America and Northern Europe

- Particularly common in elderly populations, with significantly higher isolation rates in patients >70 years

- Emerging as a leading cause of healthcare-associated fungal infections

- Frequently isolated from intensive care units and surgical wards

- Increasing recognition as a significant nosocomial pathogen

- Surveillance studies show rising proportion of C. glabrata among Candida bloodstream isolates

Diagnostic Considerations:

- Challenging to identify microscopically due to small cell size

- Traditional culture methods require 24-72 hours for definitive identification

- CHROMagar produces distinctive pink to purple colonies, aiding presumptive identification

- Biochemical profiles (limited sugar assimilation) used for species confirmation

- Molecular methods including PCR and MALDI-TOF improving speed and accuracy of identification

- Blood cultures have limited sensitivity (approximately 50%) for invasive disease

- Non-culture diagnostics (β-D-glucan, mannan, PCR) increasingly used but have variable performance

- Antifungal susceptibility testing crucial due to resistance patterns

Treatment Challenges:

- Intrinsic resistance to fluconazole and reduced susceptibility to other azoles

- Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin) generally considered first-line therapy

- Emerging echinocandin resistance, particularly with prolonged exposure

- Amphotericin B effective but limited by nephrotoxicity

- Flucytosine useful in combination therapy but resistance can develop rapidly

- Limited penetration of some antifungals into biofilms and certain body sites

- Combination therapy often required for severe or refractory infections

- Source control (e.g., catheter removal) crucial for successful treatment

- Therapeutic drug monitoring increasingly important for optimizing treatment

Clinical Presentations:

- Candidemia: Often associated with central venous catheters, presenting with fever, sepsis

- Urinary Tract Infections: More common with C. glabrata than other species, especially in catheterized patients

- Intra-abdominal Infections: Following gastrointestinal surgery or perforation

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Often recurrent and difficult to treat due to azole resistance

- Oral Candidiasis: Less common than C. albicans but increasing in immunocompromised patients

- Endocarditis: Rare but serious with high mortality, particularly on prosthetic valves

- Device-associated Infections: Pacemakers, prosthetic joints, neurosurgical shunts

- Clinical manifestations often subtle compared to C. albicans infections

High-Risk Populations:

- Elderly Patients: Significantly higher prevalence compared to younger populations

- Intensive Care Unit Patients: Particularly those with prolonged stays and multiple interventions

- Transplant Recipients: Solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients

- Cancer Patients: Especially those receiving chemotherapy or with hematological malignancies

- Surgical Patients: Particularly following abdominal surgery

- Diabetic Patients: Higher colonization rates and increased risk of infection

- Patients with Indwelling Devices: Central venous catheters, urinary catheters, prosthetic devices

- Patients Receiving Broad-spectrum Antibiotics: Disruption of protective bacterial flora

Mortality and Morbidity:

- Mortality rates for invasive disease range from 40-60%, higher than C. albicans in many studies

- Delayed appropriate therapy significantly increases mortality risk

- Prolonged hospitalization and increased healthcare costs

- Frequent complications including septic shock, organ failure, and metastatic foci of infection

- Recurrent infections common, particularly in persistently immunocompromised hosts

- Long-term sequelae in survivors of invasive disease

- Significant impact on quality of life, particularly with chronic mucosal infections

- Economic burden due to prolonged hospitalization and expensive treatments

Infection Control Considerations:

- Potential for nosocomial transmission, particularly in intensive care settings

- Environmental persistence on surfaces and medical equipment

- Hand hygiene crucial for preventing transmission

- Antifungal stewardship programs increasingly important

- Surveillance cultures in high-risk units may identify colonized patients

- Isolation precautions generally not required except for multidrug-resistant strains

- Proper disinfection of reusable medical equipment essential

- Outbreak investigation protocols for clusters of infections

Emerging Research and Future Directions:

- Novel diagnostic approaches including T2 magnetic resonance and metagenomic sequencing

- New antifungal classes in development (e.g., fosmanogepix, ibrexafungerp)

- Immunotherapeutic approaches including vaccines and monoclonal antibodies

- Biofilm-targeting strategies to overcome treatment resistance

- Host-directed therapies to enhance immune clearance

- Microbiome-based approaches to prevent C. glabrata overgrowth

- Personalized treatment strategies based on strain characteristics and host factors

- Improved risk prediction models to guide prophylaxis and empiric therapy

The clinical relevance of C. glabrata has increased substantially in recent decades, driven by the growing population of susceptible hosts, widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapies, and the organism's intrinsic resistance to commonly used antifungal agents. The challenges in diagnosis and treatment of C. glabrata infections highlight the need for improved diagnostic methods, novel antifungal agents, and effective infection prevention strategies. As antifungal resistance continues to emerge, a multifaceted approach incorporating antifungal stewardship, infection control, and development of alternative therapeutic strategies will be essential to address the growing threat posed by this opportunistic fungal pathogen.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Candida glabrata engages in complex interactions with diverse microorganisms across various human body niches, influencing both microbial community dynamics and host health:

Bacterial-Fungal Antagonism:

- Lactobacillus species inhibit C. glabrata growth through:

- Production of lactic acid creating unfavorable pH

- Secretion of hydrogen peroxide with antifungal activity

- Production of bacteriocins that target fungal cells

- Competition for adhesion sites and nutrients

- Escherichia coli can suppress C. glabrata through nutrient competition

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces molecules that inhibit fungal growth

- Streptococcus mutans produces acids and bacteriocins with anti-Candida activity

- Antagonistic interactions help maintain fungal homeostasis in healthy individuals

- Disruption of these interactions (e.g., through antibiotics) can lead to C. glabrata overgrowth

- Lactobacillus species inhibit C. glabrata growth through:

Bacterial-Fungal Synergism:

- Staphylococcus aureus can form mixed biofilms with C. glabrata, enhancing survival of both organisms

- Some streptococcal species may facilitate C. glabrata adhesion to mucosal surfaces

- Enterococcus faecalis can protect C. glabrata from some antifungal agents in mixed biofilms

- Certain anaerobic bacteria may create favorable microenvironments for C. glabrata growth

- Synergistic interactions can increase resistance to antimicrobials and host defenses

- Co-infection with certain bacteria can lead to more severe disease manifestations

- Mixed-species biofilms often demonstrate enhanced structural integrity and resistance properties

Interactions with Other Candida Species:

- Often co-exists with C. albicans in various body sites

- Competition with C. albicans for adhesion sites and nutrients

- C. albicans may create favorable conditions for C. glabrata colonization in some contexts

- C. glabrata can utilize farnesol produced by C. albicans as a quorum sensing molecule

- Mixed Candida species biofilms demonstrate altered drug resistance profiles

- Sequential colonization patterns observed in some body sites

- Species interactions influence community structure and stability

- Treatment of one Candida species may lead to overgrowth of another

Metabolic Interactions:

- Limited cross-feeding relationships due to C. glabrata's restricted metabolic capabilities

- May utilize short-chain fatty acids produced by anaerobic gut bacteria

- Competition for limited nutrients such as glucose in mixed communities

- Adaptation to microenvironments created by bacterial metabolism

- Oxygen consumption by aerobic bacteria may create favorable niches for C. glabrata

- Competition for essential micronutrients, particularly iron and zinc

- Metabolic byproducts can influence growth and virulence of community members

- Nutrient limitation in mixed communities can trigger stress responses and alter virulence

Biofilm Dynamics:

- Forms robust single-species biofilms on both biotic and abiotic surfaces

- Participates in complex polymicrobial biofilms, particularly in the oral cavity

- Spatial organization within mixed biofilms influenced by species interactions

- Extracellular matrix components from different species contribute to overall biofilm architecture

- Altered gene expression in mixed-species versus single-species biofilms

- Enhanced resistance to antimicrobials in polymicrobial biofilms

- Interspecies communication influences biofilm formation and dispersal

- Biofilm lifestyle provides protection against environmental stressors

Influence on Virulence Expression:

- Bacterial products can modulate C. glabrata virulence factor expression

- Presence of certain bacteria may enhance or suppress adhesin expression

- Stress responses triggered by microbial interactions can alter virulence profiles

- Competition in mixed communities may select for more virulent strains

- Quorum sensing molecules from various species influence collective behavior

- Virulence modulation affects pathogenic potential and host immune responses

- Interspecies interactions can alter antifungal susceptibility patterns

- Environmental adaptation in mixed communities can enhance persistence

Impact on Host Responses:

- Mixed fungal-bacterial communities elicit different immune responses than single-species infections

- Bacterial-fungal interactions can enhance or suppress inflammatory responses

- Some bacterial species may protect against C. glabrata infection by stimulating protective immunity

- C. glabrata can influence bacterial recognition by host immune cells

- Polymicrobial interactions affect epithelial barrier function and mucosal immunity

- Host responses to mixed communities can differ from the sum of responses to individual species

- Immunomodulatory effects of microbial interactions influence disease progression

Clinical Implications of Polymicrobial Interactions:

- Mixed infections often more difficult to treat than single-species infections

- Bacterial-fungal interactions can influence antifungal and antibiotic efficacy

- Antibiotic treatment can disrupt protective bacterial communities, leading to C. glabrata overgrowth

- Diagnostic challenges in distinguishing polymicrobial infections from single-species infections

- Treatment strategies increasingly considering the polymicrobial nature of many infections

- Probiotic approaches targeting beneficial bacteria may help control C. glabrata overgrowth

- Understanding microbial interactions crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies

The interactions between C. glabrata and other microorganisms represent a complex ecological network that influences both microbial community dynamics and host health. These interactions range from antagonistic relationships that help maintain homeostasis to synergistic associations that can enhance pathogenicity. The disruption of normal microbial communities, particularly through antibiotic use, can alter these interactions and create opportunities for C. glabrata overgrowth and pathogenicity. Understanding the mechanisms and consequences of these interactions provides insights into the ecological role of C. glabrata in the human microbiome and may inform novel approaches to preventing and treating C. glabrata infections. As research continues to elucidate the intricate relationships between fungi and bacteria in human-associated microbial communities, new strategies for manipulating these interactions to promote health may emerge.

Research Significance

Candida glabrata holds substantial research significance across multiple scientific disciplines, with implications for basic biology, clinical medicine, and biotechnology:

Evolutionary and Comparative Genomics:

- Provides insights into fungal evolution and adaptation to mammalian hosts

- Unique position as a haploid yeast more closely related to Saccharomyces than to other Candida species

- Model for studying genome plasticity and chromosomal rearrangements

- Comparative genomics with C. albicans reveals divergent evolutionary strategies for pathogenicity

- Natural laboratory for studying parallel evolution of virulence traits

- Insights into evolution of antifungal resistance mechanisms

- Model for studying adaptation to different host niches

- Genomic studies reveal mechanisms of host-pathogen co-evolution

Antifungal Resistance Mechanisms:

- Premier model for studying intrinsic and acquired azole resistance

- Elucidation of novel resistance mechanisms applicable to other fungal pathogens

- Platform for developing and testing new antifungal compounds

- Insights into biofilm-associated resistance phenotypes

- Model for studying the emergence and spread of resistance in clinical settings

- Understanding of resistance mechanisms informs antifungal stewardship strategies

- Identification of potential targets for resistance-breaking adjuvant therapies

- Predictive models for resistance development guide clinical decision-making

Host-Pathogen Interactions:

- Model for studying fungal survival within phagocytic cells

- Insights into mechanisms of immune evasion without hyphal formation

- Understanding of host recognition pathways for non-filamentous fungi

- Elucidation of stress response mechanisms during host-pathogen encounters

- Model for studying the transition from commensalism to pathogenicity

- Insights into host factors that influence susceptibility to infection

- Platform for developing immunotherapeutic approaches

- Understanding of tissue tropism and organ-specific pathogenesis

Biofilm Biology:

- Model for studying fungal biofilm formation and regulation

- Insights into biofilm-associated drug resistance mechanisms

- Understanding of polymicrobial biofilm dynamics

- Elucidation of biofilm matrix composition and function

- Platform for testing anti-biofilm strategies

- Model for studying biofilm formation on medical devices

- Insights into biofilm dispersal mechanisms

- Understanding of biofilm-host interactions

Microbial Ecology and Microbiome Research:

- Model for studying fungal-bacterial interactions in the human microbiome

- Insights into factors governing microbial community assembly and stability

- Understanding of the mycobiome component of the human microbiota

- Elucidation of mechanisms underlying dysbiosis and its consequences

- Model for studying competition and cooperation in microbial communities

- Insights into the impact of antibiotics on fungal-bacterial balance

- Platform for developing microbiome-based therapeutic approaches

- Understanding of spatial and temporal dynamics in microbial communities

Biotechnological Applications:

- Potential chassis for production of biopharmaceuticals

- Model for studying and engineering stress tolerance in industrial yeasts

- Source of enzymes and metabolites with industrial applications

- Platform for screening antifungal compounds

- Development of biosensors for environmental monitoring

- Insights into cell wall biology applicable to industrial processes

- Model for studying and manipulating adhesion properties

- Potential applications in bioremediation

Clinical Research Advances:

- Development of improved diagnostic methods for invasive candidiasis

- Identification of biomarkers for early detection and treatment response

- Risk prediction models to guide prophylaxis and empiric therapy

- Clinical trials of novel antifungal agents and combination therapies

- Epidemiological studies tracking emergence and spread of resistant strains

- Evaluation of infection prevention strategies in healthcare settings

- Assessment of host-directed therapies to enhance immune clearance

- Development of personalized treatment approaches based on strain characteristics

Future Research Directions:

- Integration of multi-omics approaches to understand C. glabrata in complex environments

- Development of targeted approaches to disrupt pathogenicity while preserving commensal functions

- Exploration of the role of C. glabrata in complex diseases beyond traditional infections

- Investigation of C. glabrata interactions with the virome and parasitome

- Application of systems biology approaches to model C. glabrata behavior in diverse contexts

- Development of immunotherapeutic strategies targeting fungal-specific pathways

- Exploration of the impact of climate change on fungal ecology and epidemiology

- Novel approaches to overcome antifungal resistance and biofilm-associated infections

The research significance of C. glabrata extends from fundamental questions about fungal biology and evolution to practical applications in medicine and biotechnology. As a successful human-associated yeast with increasing clinical importance, C. glabrata provides unique opportunities to study the factors that enable adaptation to the human host and the transition from commensalism to pathogenicity. The intrinsic antifungal resistance and remarkable stress tolerance of C. glabrata make it particularly valuable for understanding and addressing the growing challenge of drug-resistant fungal infections. Continued research on this important fungal species promises to yield insights that will advance our understanding of fungal biology, host-microbe interactions, and approaches to preventing and treating fungal diseases. The translational potential of C. glabrata research is substantial, with implications for improving diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of fungal infections that affect millions of people worldwide.