Neisseria meningitidis

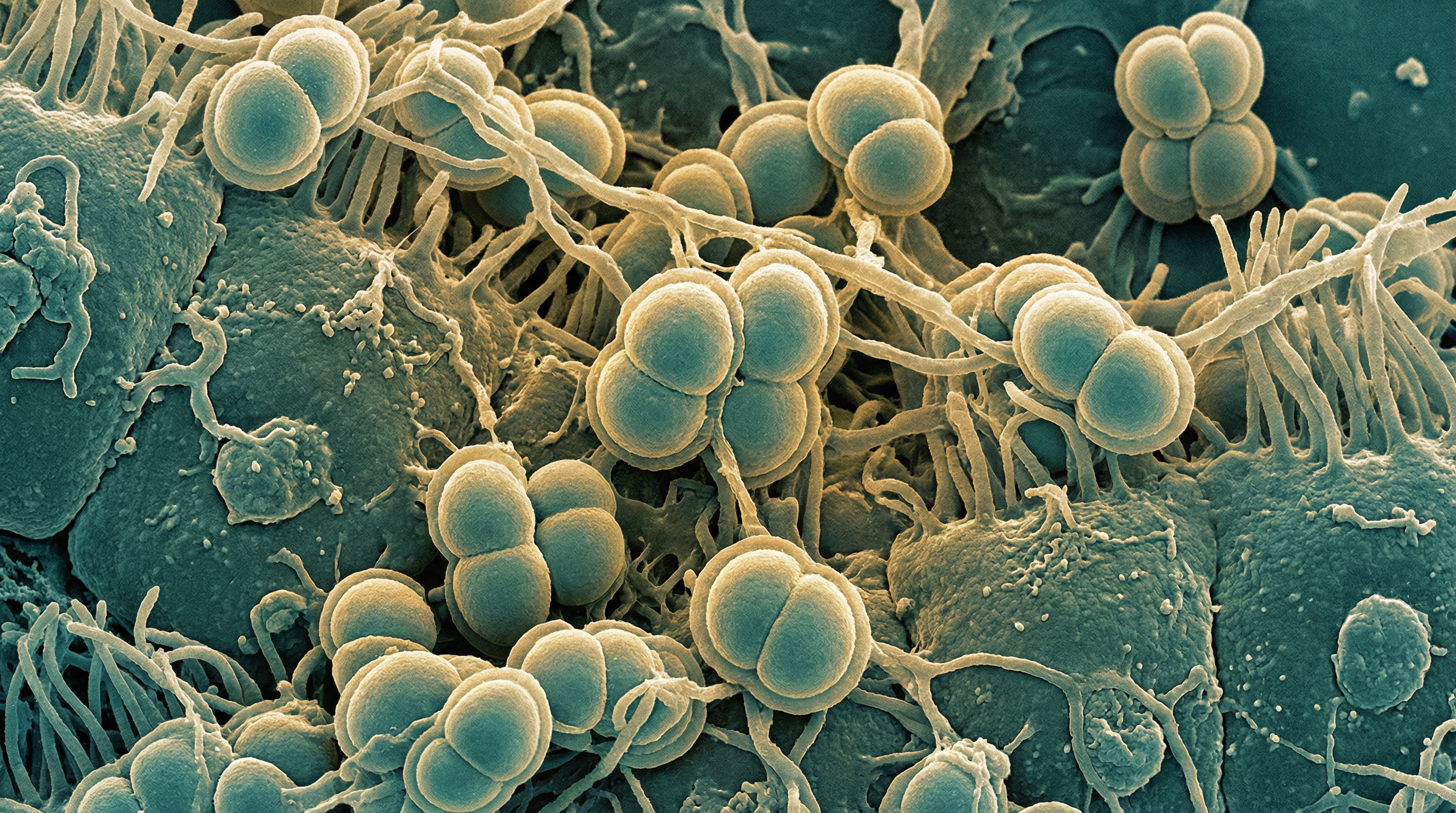

Neisseria meningitidis, commonly known as meningococcus, is a gram-negative diplococcus bacterium that colonizes the human nasopharynx. While often existing as a commensal organism, it is primarily known for its potential to cause invasive meningococcal disease, including meningitis and septicemia, which can be rapidly progressive and life-threatening.

Key Characteristics

N. meningitidis is a member of the family Neisseriaceae and appears microscopically as kidney bean-shaped cocci in pairs. The bacterium is aerobic (though facultatively anaerobic), non-motile, and produces catalase and oxidase. It has complex nutritional requirements and grows optimally on chocolate or blood agar in a humidified environment with 5-10% carbon dioxide.

A distinguishing feature of N. meningitidis is its polysaccharide capsule, which forms the basis for serogroup classification. Thirteen serogroups have been identified, with six (A, B, C, W, X, and Y) accounting for most invasive disease globally. The bacterium also possesses pili and outer membrane proteins that facilitate adherence to host cells and contribute to virulence.

N. meningitidis oxidizes glucose and maltose to acid, which distinguishes it from N. gonorrhoeae (which oxidizes only glucose) and N. lactamica (which can ferment lactose).

Role in Human Microbiome

N. meningitidis primarily colonizes the human nasopharynx, with carriage rates varying by age, geographic location, and living conditions. In general:

- Carriage rates are low in early childhood (1-3%)

- Rates increase during adolescence and early adulthood (10-35%)

- Rates decrease in older adults (3-10%)

Carriage is generally asymptomatic and may last for months. The bacterium is exclusively human-adapted with no animal or environmental reservoir. Transmission occurs through respiratory droplets or direct contact with respiratory secretions from carriers or infected individuals.

While N. meningitidis is primarily known for its pathogenic potential, it is important to recognize that asymptomatic carriage is far more common than invasive disease, suggesting that in most host-microbe interactions, it functions as part of the normal nasopharyngeal microbiota.

Health Implications

Pathogenic Potential

N. meningitidis is capable of causing invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), which primarily manifests as:

Meningitis: Inflammation of the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord, characterized by fever, headache, neck stiffness, and altered mental status.

Meningococcemia (septicemia): Bloodstream infection that can lead to septic shock, characterized by fever, petechial or purpuric rash, and rapid progression to multi-organ failure.

Combined meningitis and septicemia: Many patients present with both conditions simultaneously.

Less common manifestations include pneumonia, arthritis, pericarditis, and urethritis.

The case fatality rate for invasive meningococcal disease ranges from 10-15% even with appropriate treatment, and up to 20% of survivors experience long-term sequelae including neurological deficits, hearing loss, limb amputations, and cognitive impairments.

Risk Factors for Invasive Disease

Several factors increase the risk of progression from asymptomatic carriage to invasive disease:

- Age (highest in infants and adolescents)

- Complement deficiencies (particularly C5-C9, properdin, or factor D)

- Asplenia or splenic dysfunction

- HIV infection

- Crowded living conditions (military barracks, college dormitories)

- Recent upper respiratory tract infections

- Active or passive smoking

- Genetic polymorphisms in immune response genes

Protective Factors

Natural immunity against N. meningitidis develops through:

- Asymptomatic carriage of N. meningitidis

- Cross-reactive immunity from colonization with non-pathogenic Neisseria species, particularly N. lactamica

- Exposure to environmental bacteria expressing cross-reactive antigens

Metabolic Activities

N. meningitidis has adapted to the human nasopharyngeal environment with specialized metabolic capabilities:

- Utilization of glucose and maltose as primary carbon sources

- Acquisition of iron through specialized receptors for human transferrin and lactoferrin

- Metabolism of lactate produced by other respiratory microbiota

- Adaptation to microaerobic conditions in mucosal surfaces

- Production of IgA1 protease to cleave human immunoglobulin A

These metabolic adaptations reflect its highly specialized niche as a human-restricted organism.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical significance of N. meningitidis centers on its role as a leading cause of bacterial meningitis and septicemia:

Epidemiology: Causes approximately 1.2 million cases of invasive disease annually worldwide, with the highest burden in the "meningitis belt" of sub-Saharan Africa.

Diagnosis: Rapid diagnosis is critical and involves cerebrospinal fluid analysis, blood cultures, PCR, and antigen detection tests.

Treatment: Immediate antibiotic therapy (typically third-generation cephalosporins) is essential, along with supportive care and management of complications.

Prevention: Vaccines are available against serogroups A, C, W, Y, and B. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended for close contacts of cases.

Antimicrobial resistance: Emerging resistance to penicillin and other antibiotics is a growing concern, though most isolates remain susceptible to recommended treatments.

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

N. meningitidis interacts with various members of the nasopharyngeal microbiome:

Competition with N. lactamica: Epidemiological evidence suggests that N. lactamica colonization provides protection against N. meningitidis carriage and disease, likely through competition for the same ecological niche.

Horizontal gene transfer: N. meningitidis can acquire DNA from other Neisseria species and other bacteria in the nasopharynx, which has contributed to the development of antibiotic resistance and antigenic variation.

Co-colonization effects: The presence of other respiratory bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae may influence N. meningitidis carriage dynamics and potentially trigger invasion through inflammation-induced changes in the nasopharyngeal environment.

Viral interactions: Viral respiratory infections may damage the nasopharyngeal epithelium and facilitate meningococcal invasion, explaining the seasonal pattern of meningococcal disease that often follows viral respiratory seasons.

Research Significance

N. meningitidis remains an important focus of research for several reasons:

Vaccine development: Ongoing efforts to improve vaccines, particularly against serogroup B and to develop universal vaccines covering all serogroups.

Host-pathogen interactions: Understanding the molecular mechanisms that determine the switch from asymptomatic carriage to invasive disease.

Genomic diversity: Studying the extensive genetic diversity and rapid evolution of this organism to predict emergence of hypervirulent lineages.

Microbiome interactions: Investigating how the nasopharyngeal microbiome influences meningococcal carriage and disease risk.

Antimicrobial resistance: Monitoring and addressing emerging resistance patterns.

Novel therapeutics: Developing new approaches to prevent and treat meningococcal disease, including monoclonal antibodies and anti-virulence strategies.

References

Stephens DS, Greenwood B, Brandtzaeg P. Epidemic meningitis, meningococcaemia, and Neisseria meningitidis. Lancet. 2007;369(9580):2196-2210.

Caugant DA, Maiden MC. Meningococcal carriage and disease--population biology and evolution. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 2):B64-B70.

Christensen H, May M, Bowen L, et al. Meningococcal carriage by age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):853-861.

Harrison LH, Trotter CL, Ramsay ME. Global epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 2):B51-B63.

Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, et al. Meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1378-1388.

Yazdankhah SP, Caugant DA. Neisseria meningitidis: an overview of the carriage state. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(Pt 9):821-832.