Pectin

A gel-forming soluble fiber from fruits that supports diverse gut bacteria, promotes SCFA production, and aids digestive health.

Food Sources

Naturally found in these foods:

Key Benefits

- Promotes diverse gut bacteria

- Supports butyrate production

- May lower cholesterol

- Aids glycemic control

- Supports gut barrier function

Bacteria This Prebiotic Feeds

This prebiotic selectively nourishes these beneficial microorganisms:

Overview

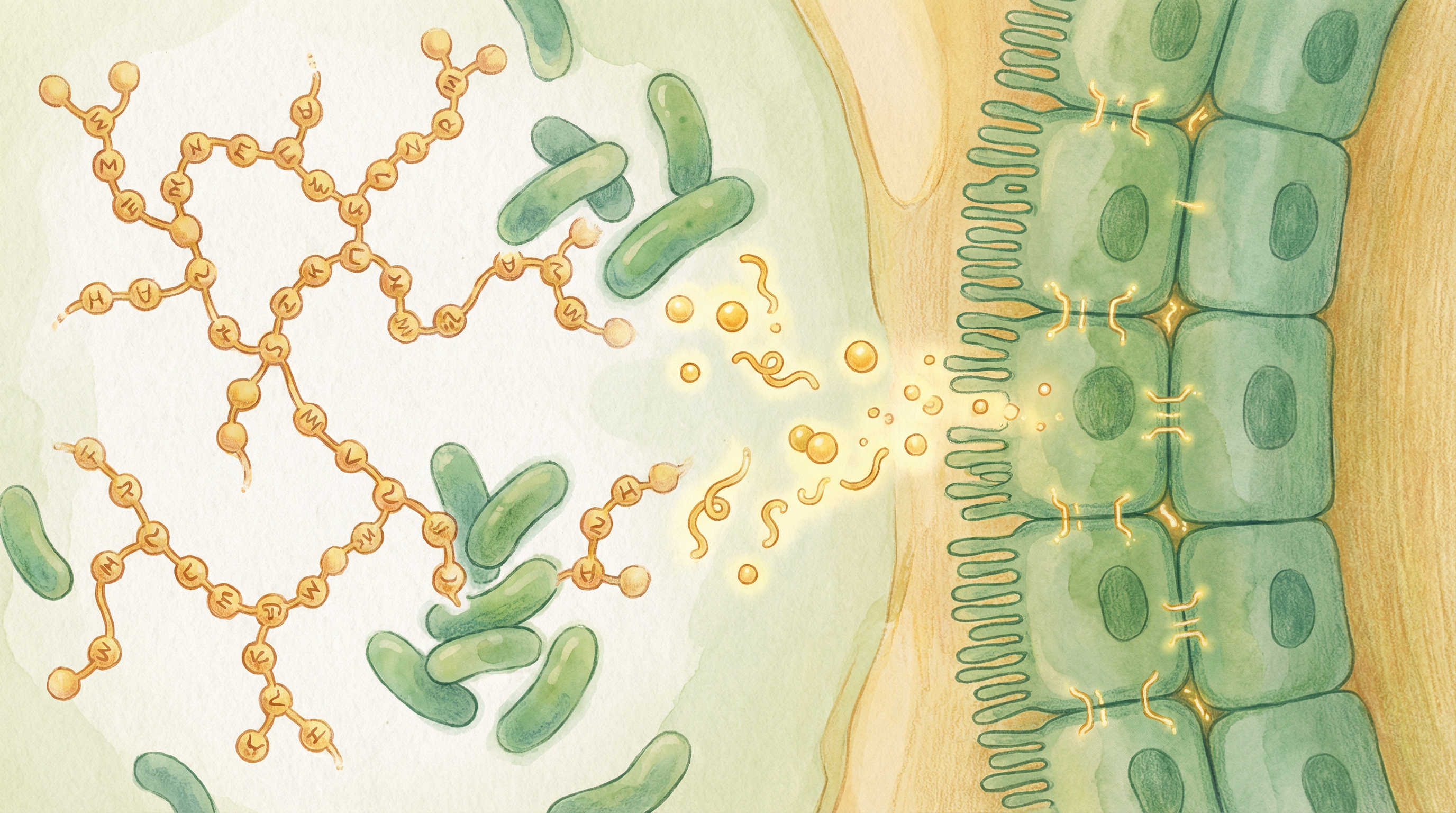

Pectin is a complex heteropolysaccharide found in the cell walls and intercellular spaces of plants, serving as a structural component and providing firmness to fruits[1]. As a soluble dietary fiber, pectin has long been recognized for its gel-forming properties in food applications, but it is increasingly valued for its prebiotic effects on the gut microbiome. The structural diversity of pectin allows it to support a wide range of beneficial bacteria, promoting a healthy, diverse gut ecosystem.

Structure and Types

Pectin's complex structure contributes to its diverse functions[5]:

Structural Domains

- Homogalacturonan (HG): Linear backbone of galacturonic acid; most abundant domain

- Rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I): Branched region with diverse side chains

- Rhamnogalacturonan-II (RG-II): Highly conserved, complex branched structure

Key Structural Features

- Degree of methylation (DM): Affects gel properties and fermentation

- High methoxyl (HM) pectin: DM >50%, gels with sugar and acid

- Low methoxyl (LM) pectin: DM <50%, gels with calcium

- Molecular weight: Varies widely, affecting viscosity and fermentation

Sources

Different fruits and vegetables contain pectins with varying structures:

- Citrus peel: 20-30% pectin (primarily HM)

- Apple pomace: 10-15% pectin

- Sugar beet pulp: 15-25% pectin (rich in RG-I)

- Berries, carrots, plums: Moderate pectin content

Mechanism of Action

Prebiotic Fermentation

Pectin's prebiotic effects arise from its selective fermentation by gut bacteria[4]:

- Initial degradation: Bacteroides species possess pectinolytic enzymes for initial breakdown

- Cross-feeding: Degradation products become available to other bacteria

- SCFA production: Fermentation yields acetate, propionate, and butyrate

- Selective growth: Different pectin structures favor different bacterial species

Research has shown that microbial utilization varies based on pectin structure:

- Low DM pectins are more readily fermented

- RG-I domains promote different bacteria than HG domains

- Structural diversity supports microbiome diversity

Promotion of Anti-Inflammatory Bacteria

Studies demonstrate pectin's ability to promote anti-inflammatory commensal bacteria[3]:

- Increases Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abundance

- Enhances Bifidobacterium populations

- Supports Lactobacillus growth

- Promotes butyrate-producing species

SCFA Production

Pectin fermentation is a significant source of short-chain fatty acids[6]:

- Acetate: Most abundant SCFA from pectin fermentation

- Propionate: Significant production, influences hepatic metabolism

- Butyrate: Key energy source for colonocytes, anti-inflammatory

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Primary Effects

- Bifidobacterium: Consistently enhanced with pectin supplementation

- Lactobacillus: Supported by pectin oligosaccharides

- Bacteroides: Key degraders of intact pectin polymers

- Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: Major butyrate producer, promoted by pectin

Structure-Dependent Effects

Different pectin fractions show varying selectivity[4]:

| Pectin Type | Primary Bacteria Supported |

|---|---|

| Low DM pectin | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides |

| High DM pectin | Slower fermentation, more distal colon effects |

| RG-I rich | Faecalibacterium, diverse species |

| Pectic oligosaccharides | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus |

Microbiome Diversity

Unlike some prebiotics that predominantly feed one bacterial group, pectin's structural complexity supports broader microbiome diversity[2]:

- Multiple bacterial species involved in degradation

- Cross-feeding networks established

- Both saccharolytic and proteolytic bacteria affected

- Overall community structure improved

Health Benefits

Digestive Health

Pectin supports gut health through multiple mechanisms:

- Enhanced SCFA production for colonocyte nutrition

- Improved gut barrier function

- Increased mucus production

- Modulated intestinal immune responses

Cardiovascular Health

Pectin has well-documented effects on cardiovascular risk factors[1]:

- Cholesterol reduction: 6-15g daily can reduce LDL cholesterol

- Mechanism: Bile acid binding and increased excretion

- Additional effects: May lower blood pressure

Glycemic Control

Pectin's gel-forming properties influence glucose metabolism:

- Slows gastric emptying

- Reduces glucose absorption rate

- Improves postprandial glycemia

- May enhance insulin sensitivity

Satiety and Weight Management

The viscosity of pectin solutions contributes to:

- Increased satiety signaling

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Reduced energy intake

- Potential support for weight management

Clinical Applications

Diarrhea Management

Pectin has traditional use in managing diarrhea:

- Absorbs excess water in the intestine

- Supports beneficial bacteria recovery

- May reduce duration of acute diarrhea

- Often combined with kaolin in OTC preparations

Gut Health Support

Regular pectin consumption supports:

- Microbiome diversity

- SCFA production

- Gut barrier integrity

- Anti-inflammatory environment

Dosage and Sources

Dietary Intake

Average dietary pectin intake is 2-6g daily, with higher intakes in fruit-rich diets[1].

Supplemental Dosage

- Prebiotic effects: 6-15g daily

- Cholesterol lowering: 6-15g daily

- General gut health: 3-10g daily

Rich Food Sources

| Food | Pectin Content (g/100g fresh) |

|---|---|

| Citrus peel | 20-30 |

| Apple (with skin) | 0.5-1.6 |

| Apricots | 0.4-1.0 |

| Carrots | 0.4-0.8 |

| Plums | 0.5-1.0 |

| Berries | 0.3-0.8 |

Supplement Forms

- Citrus pectin: Most common supplement form

- Modified citrus pectin (MCP): Processed for enhanced absorption

- Apple pectin: Alternative source

- Pectic oligosaccharides: Pre-degraded for faster fermentation

Practical Recommendations

Dietary Strategies

- Include whole fruits rather than juices

- Consume fruits with skin when appropriate

- Include citrus in the diet regularly

- Eat a variety of pectin-rich vegetables

Supplementation

- Start with 3-5g daily

- Increase gradually to target dose

- Take with adequate water

- Divide doses throughout the day

Safety and Tolerability

Pectin is generally very safe:

- Long history of food use

- GRAS status

- Well-tolerated at moderate doses

- May cause gas and bloating initially

Considerations

- High doses may interfere with mineral absorption

- Drug absorption may be affected (take separately)

- Gradual introduction recommended

- Adequate hydration important

Summary

Pectin represents a valuable prebiotic fiber distinguished by its structural complexity and ability to support diverse gut bacteria. Unlike simpler prebiotics that primarily feed Bifidobacterium, pectin's heterogeneous structure promotes a broader range of beneficial species, including the important butyrate producer Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Combined with its well-established benefits for cardiovascular health and glycemic control, pectin from dietary sources or supplements offers comprehensive support for gut microbiome health and overall metabolic wellness.

Dosage Guidelines

Recommended Dosage

6-15g daily

Start with a lower dose and gradually increase to minimize digestive discomfort. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized recommendations.

References

- Lattimer JM, Haub MD. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients. 2010;2(12):1266-1289. doi:10.3390/nu2121266

- Tian L, Scholte J, Borewicz K, et al.. Effects of pectin supplementation on the fermentation patterns of different structural carbohydrates in rats. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2016;60(10):2256-2266. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201600149

- Chung WSF, Meijerink M, Zeuner B, et al.. Prebiotic potential of pectin and pectic oligosaccharides to promote anti-inflammatory commensal bacteria in the human colon. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2017;93(11):fix127. doi:10.1093/femsec/fix127

- Onumpai C, Kolida S, Bonnin E, Rastall RA. Microbial utilization and selectivity of pectin fractions with various structures. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77(16):5747-5754. doi:10.1128/AEM.00179-11

- Wu D, Zheng J, Mao G, et al.. Rethinking the impact of RG-I mainly from fruits and vegetables on dietary health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;60(17):2938-2960. doi:10.1080/10408398.2019.1672037

- Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332-1345. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041