Pathogenic Bacteria: Understanding Harmful Gut Microbes & How to Protect Yourself

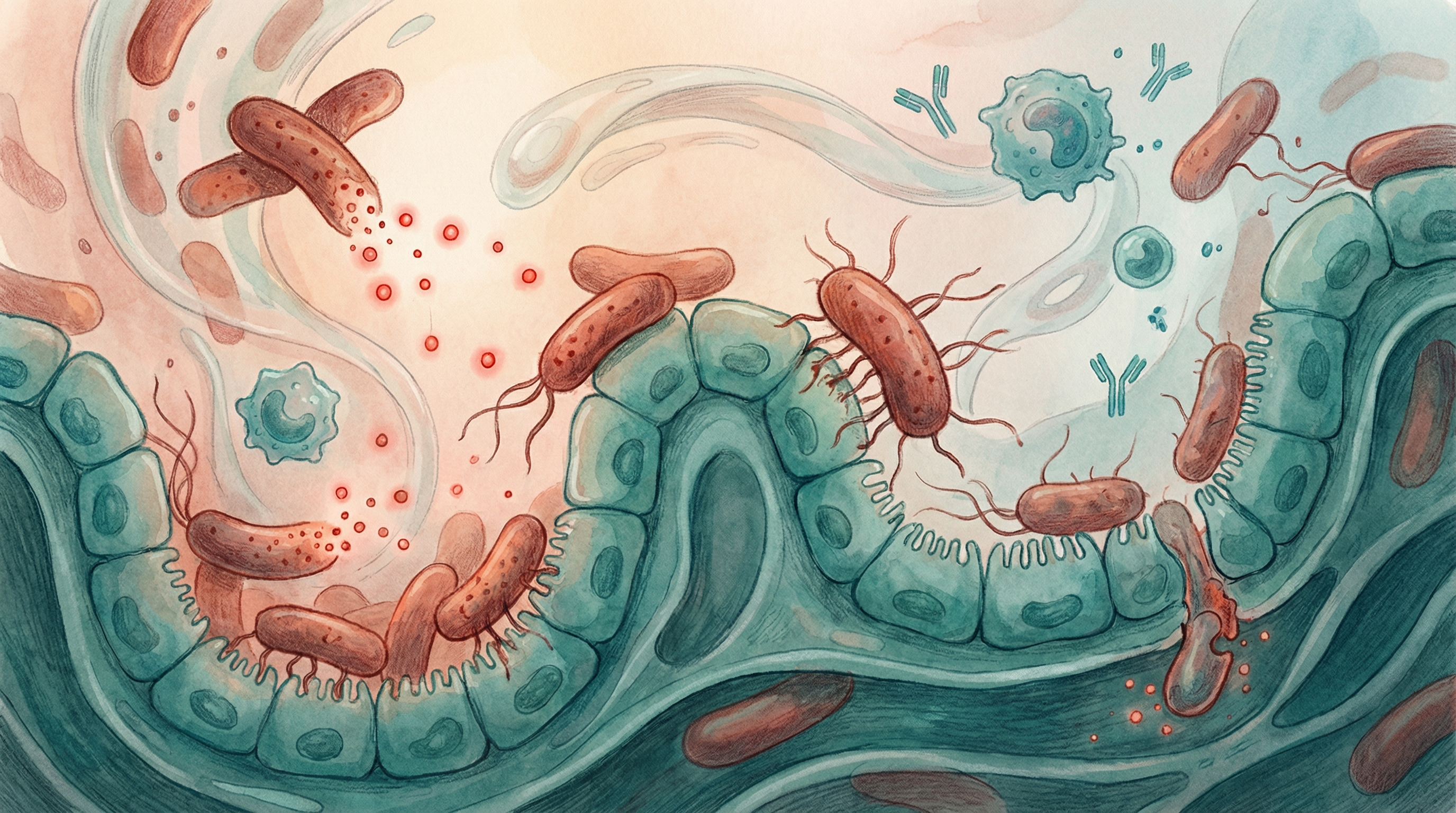

While most gut bacteria are neutral or beneficial, some microorganisms can cause serious illness. Understanding pathogenic bacteria—their mechanisms, risk factors, and prevention strategies—is essential for protecting your gut health and overall wellbeing[1].

What Makes Bacteria Pathogenic?

Pathogenic bacteria are microorganisms capable of causing disease in their host. They're distinguished by specific characteristics:

Virulence Factors

Pathogens possess tools that enable them to cause harm[1]:

- Adhesins: Proteins that help bacteria attach to intestinal cells

- Toxins: Harmful substances that damage tissues or disrupt cell function

- Invasins: Enable bacteria to penetrate host tissues

- Capsules: Protective coatings that help evade immune defenses

- Enzymes: Break down tissue barriers or interfere with immune responses

The Pathogen-Host Interaction

Disease occurs through a multi-step process:

- Exposure: Contact with the pathogen (contaminated food, person-to-person transmission)

- Colonization: Pathogen establishes presence in the gut

- Invasion or toxin production: Damage to host tissues

- Disease manifestation: Symptoms appear

- Transmission or resolution: Spread to others or recovery

Common Pathogenic Bacteria in the Gut

Clostridioides difficile (C. diff)

One of the most concerning gut pathogens, especially in healthcare settings[3]:

Characteristics:

- Spore-forming bacterium that survives outside the body

- Causes antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Can lead to life-threatening colitis

Risk factors:

- Antibiotic use (disrupts protective bacteria)

- Hospitalization

- Age over 65

- Weakened immune system

- Proton pump inhibitor use

Prevention:

- Judicious antibiotic use

- Hand hygiene (alcohol gels don't kill spores—soap and water required)

- Probiotic supplementation during antibiotic courses (Saccharomyces boulardii shows benefit)

- Maintaining healthy gut microbiome diversity

Salmonella Species

A leading cause of foodborne illness worldwide:

Characteristics:

- Causes salmonellosis (food poisoning)

- Can become invasive in vulnerable individuals

- Found in undercooked eggs, poultry, contaminated produce

Symptoms:

- Diarrhea (often bloody)

- Fever and abdominal cramps

- Onset 12-72 hours after exposure

- Usually resolves in 4-7 days

Prevention:

- Proper food handling and cooking

- Avoiding cross-contamination in kitchens

- Hand washing after handling raw meat

- Avoiding raw eggs in vulnerable populations

Pathogenic Escherichia coli

While most E. coli are harmless commensals, certain strains cause serious disease:

EHEC (Enterohemorrhagic E. coli, including O157:H7):

- Produces Shiga toxin

- Causes bloody diarrhea

- Can lead to hemolytic uremic syndrome (kidney failure)

- Found in undercooked ground beef, raw milk, contaminated vegetables

ETEC (Enterotoxigenic E. coli):

- Major cause of travelers' diarrhea

- Produces heat-labile and/or heat-stable toxins

- Watery diarrhea without blood

- Transmitted through contaminated food and water

Campylobacter Species

The most common bacterial cause of gastroenteritis in developed countries:

Characteristics:

- Causes campylobacteriosis

- Often linked to undercooked poultry

- Can trigger post-infectious complications

Complications:

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (rare autoimmune nerve disorder)

- Reactive arthritis

- Irritable bowel syndrome development

Vibrio Species

Include both cholera-causing strains and others:

Vibrio cholerae:

- Causes cholera

- Severe watery diarrhea leading to dehydration

- Transmitted through contaminated water

- Rare in developed countries

Vibrio parahaemolyticus:

- Associated with raw or undercooked seafood

- Causes gastroenteritis

- More common in coastal areas

Helicobacter pylori

While primarily a stomach pathogen, H. pylori significantly impacts gut health:

Characteristics:

- Colonizes stomach lining

- Causes peptic ulcers and chronic gastritis

- Risk factor for stomach cancer

- Present in roughly half the world's population

Treatment:

- Triple or quadruple antibiotic therapy

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Eradication can alter overall gut microbiome

How the Healthy Microbiome Protects Against Pathogens

Your beneficial bacteria form a crucial defense against pathogens—a concept called colonization resistance[5]:

Competitive Exclusion

Beneficial bacteria outcompete pathogens by:

- Occupying ecological niches

- Consuming available nutrients

- Maintaining acidic pH through metabolite production

- Physically blocking attachment sites

Antimicrobial Production

Good bacteria produce substances that inhibit pathogens:

- Bacteriocins (antimicrobial peptides)

- Organic acids (lactic acid, acetic acid)

- Hydrogen peroxide

- Short-chain fatty acids

Immune System Support

The microbiome enhances immune defenses:

- Training immune cells to recognize threats

- Strengthening the mucus barrier

- Producing immunoglobulin A (IgA)

- Regulating inflammatory responses

Risk Factors for Pathogen Susceptibility

Microbiome Disruption

Antibiotic use is the most significant risk factor for gut infections[3]:

- Reduces colonization resistance

- Particularly concerning with broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Effects can persist for months after treatment

Other medications that alter gut bacteria:

- Proton pump inhibitors (reduce stomach acid barrier)

- NSAIDs (affect gut lining)

- Some immunosuppressants

Immune Compromise

Increased infection risk in:

- HIV/AIDS patients

- Transplant recipients

- Cancer patients on chemotherapy

- Those with primary immunodeficiencies

- Elderly individuals with age-related immune decline

Diet and Lifestyle Factors

Low-fiber diets:

- Reduce beneficial bacteria populations

- Decrease protective metabolite production

- May increase pathogen susceptibility

Excessive alcohol:

- Damages gut lining

- Alters microbiome composition

- Impairs immune function

Chronic stress:

- Affects gut-brain axis

- Alters microbiome composition

- May increase gut permeability

Protecting Yourself from Pathogenic Bacteria

Food Safety Practices

Safe food handling:

- Wash hands thoroughly before food preparation

- Separate raw meat from other foods

- Use separate cutting boards for raw meat

- Refrigerate perishables promptly

Proper cooking:

- Cook ground beef to 160°F (71°C)

- Cook poultry to 165°F (74°C)

- Avoid raw eggs in high-risk individuals

- Reheat leftovers thoroughly

Smart choices:

- Avoid unpasteurized dairy and juices

- Wash produce thoroughly

- Be cautious with raw seafood

- Check food safety notices when traveling

Supporting Your Protective Microbiome

Nurture beneficial bacteria:

- Consume fermented foods regularly

- Eat diverse, fiber-rich plant foods

- Include prebiotic fibers in your diet

- Avoid unnecessary antimicrobials in food and products

Maintain gut barrier integrity[2]:

- Consume butyrate-promoting foods

- Limit emulsifiers and artificial additives

- Manage stress through proven techniques

- Ensure adequate sleep

Antibiotic Stewardship

Only when necessary:

- Don't request antibiotics for viral infections

- Complete prescribed courses (unless advised otherwise by a doctor)

- Don't share or save antibiotics

Protective measures during treatment:

- Consider evidence-based probiotics

- Maintain healthy diet during treatment

- Support microbiome recovery afterward

When to Seek Medical Attention

Seek immediate care for:

- Bloody diarrhea

- High fever (>101.5°F/38.6°C)

- Signs of dehydration (dizziness, decreased urination, extreme thirst)

- Symptoms lasting more than 3 days

- Recent antibiotic use with severe diarrhea (possible C. difficile)

In vulnerable populations:

- Infants and young children

- Elderly individuals

- Pregnant women

- Immunocompromised individuals

- Those with chronic health conditions

Treatment Approaches

Most Gut Infections

Many bacterial gastroenteritis cases resolve without specific treatment:

- Fluid and electrolyte replacement

- Rest

- Gradual return to normal diet

- Antibiotics only when specifically indicated

Specific Pathogen Treatment

C. difficile infection[4]:

- Vancomycin or fidaxomicin (antibiotics targeting C. diff)

- Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent cases

- Bezlotoxumab (antibody against C. diff toxin) for high-risk patients

Other serious infections:

- Targeted antibiotics based on culture results

- Supportive care

- Monitoring for complications

Recovery and Microbiome Restoration

After Infection

Supporting gut health recovery:

- Gradual reintroduction of normal diet

- Probiotic-rich foods

- Adequate fiber intake

- Hydration

After Antibiotic Treatment

Microbiome recovery strategies:

- Fermented foods daily

- Diverse plant-based foods

- Prebiotic fibers (slowly introduced)

- Consider evidence-based probiotic supplements

- Allow 3-6 months for full recovery

Conclusion

Understanding pathogenic bacteria empowers you to protect your gut health effectively. While these harmful microbes pose real risks, the good news is that most infections are preventable through:

- Safe food handling practices

- A healthy, diverse microbiome

- Judicious antibiotic use

- Prompt medical attention when needed

Your gut's natural defenses—supported by beneficial bacteria—provide robust protection against most pathogens. By nurturing this protective ecosystem and practicing good hygiene, you significantly reduce your risk of gut infections.

Learn more: Explore our microbiome database to understand individual bacterial species, read about beneficial bacteria that protect against pathogens, or discover how prebiotics can strengthen your gut's natural defenses.

References

- Ducarmon QR, Zwittink RD, Hornung BVH, et al.. Gut Microbiota and Colonization Resistance against Bacterial Enteric Infection. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2019;83(3):e00007-19. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00007-19

- Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, et al.. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nature Communications. 2019;10(1):89. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07859-7

- Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(16):1539-1548. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1403772

- Brown JRM, Flemer B, Joyce SA, et al.. Changes in microbiota composition, bile and fatty acid metabolism, in successful faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile infection. BMC Gastroenterology. 2018;18(1):131. doi:10.1186/s12876-018-0860-5

- Buffie CG, Pamer EG. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(11):790-801. doi:10.1038/nri3535