Prebiotics vs Probiotics: Understanding the Difference and Why You Need Both

In the growing conversation about gut health, two terms frequently come up: prebiotics and probiotics. While they sound similar and both support digestive wellness, they work in fundamentally different ways. Understanding these differences—and how these compounds work synergistically—is essential for optimizing your microbiome and overall health.

What Are Probiotics?

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host[2]. In simpler terms, probiotics are beneficial bacteria and yeasts that you consume to support your gut microbiome.

Common Probiotic Species

The most well-researched probiotic genera include:

Lactobacillus species:

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus – Supports immune function and digestive health

- Lactobacillus acidophilus – Aids lactose digestion and pathogen exclusion

- Lactobacillus plantarum – Produces antimicrobial compounds

Bifidobacterium species:

- Bifidobacterium longum – Supports gut barrier function and immunity

- Bifidobacterium bifidum – Important for infant gut development

- Bifidobacterium lactis – Enhances immune response

Other beneficial microbes:

- Saccharomyces boulardii – A beneficial yeast preventing diarrhea

- Streptococcus thermophilus – Aids lactose digestion

Sources of Probiotics

Fermented foods:

- Yogurt with live active cultures

- Kefir (fermented milk drink)

- Sauerkraut (fermented cabbage)

- Kimchi (Korean fermented vegetables)

- Kombucha (fermented tea)

- Miso and tempeh (fermented soy products)

- Traditional pickles (lacto-fermented, not vinegar-based)

Supplements:

- Capsules and tablets

- Powders

- Liquids

- Probiotic-enriched foods

How Probiotics Work

Probiotics benefit health through several mechanisms[4]:

- Competitive exclusion: Occupying space and resources that pathogens might use

- Antimicrobial production: Creating substances like bacteriocins that inhibit harmful bacteria

- Immune modulation: Interacting with gut-associated lymphoid tissue to regulate immunity

- Barrier enhancement: Strengthening tight junctions between intestinal cells

- Metabolite production: Generating beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids

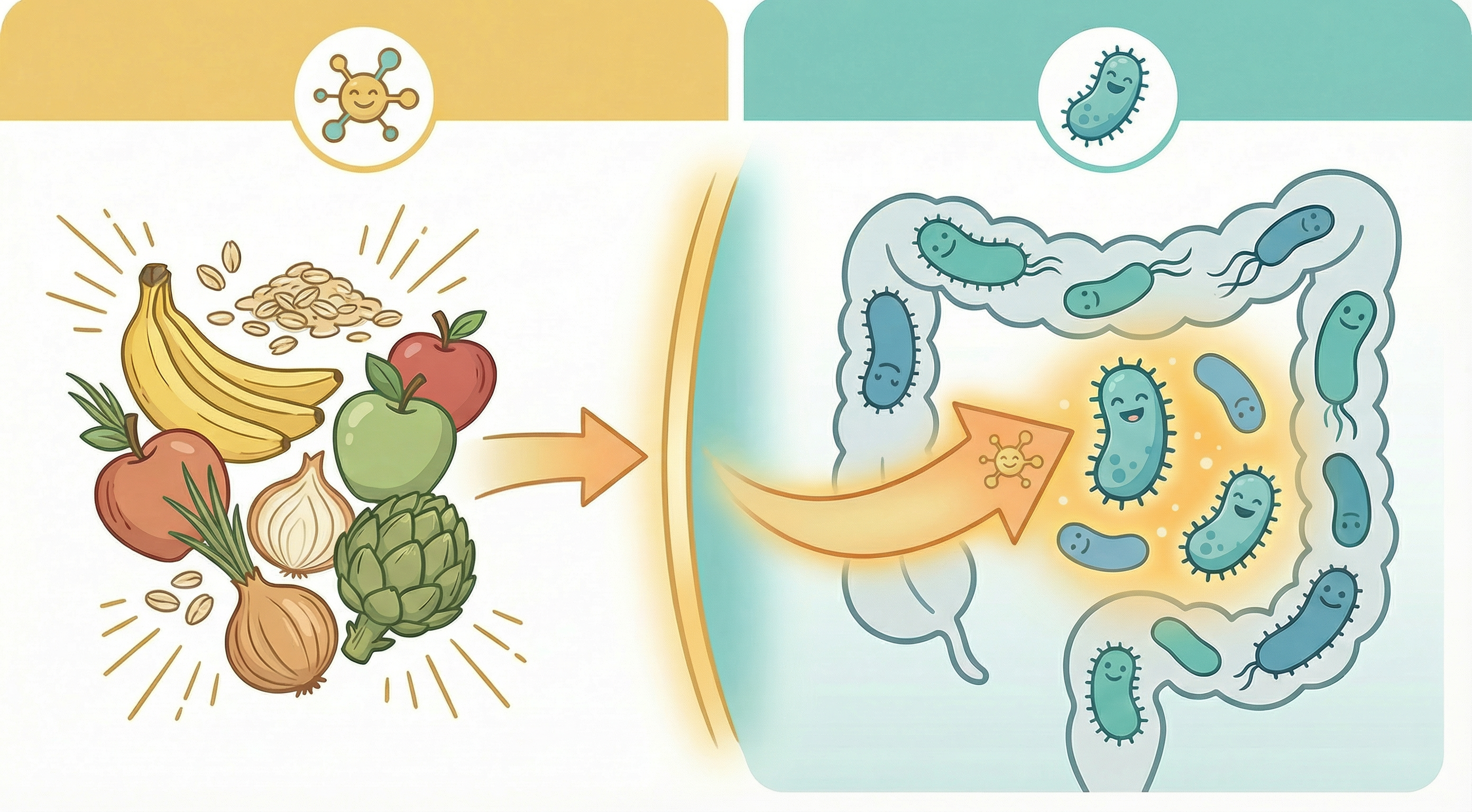

What Are Prebiotics?

Prebiotics are substrates that are selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit[1]. Essentially, prebiotics are specialized plant fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria, helping them thrive and multiply.

Types of Prebiotics

- Found in chicory root, garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus

- Selectively feeds Bifidobacterium species

- Supports calcium absorption and bone health

- Present in bananas, onions, garlic, asparagus

- Promotes growth of beneficial Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium

- Has a mildly sweet taste

- Found in legumes and some root vegetables

- Particularly beneficial for Bifidobacterium growth

- Similar to oligosaccharides in human breast milk

- Present in green bananas, cooled potatoes, legumes

- Fermented in the colon to produce butyrate

- Supports blood sugar regulation

- Found in oats, barley, mushrooms

- Supports immune function and cholesterol metabolism

- Increases Bifidobacterium populations

- Abundant in apples, citrus fruits, berries

- Promotes diverse microbial communities

- Supports gut barrier integrity

- Found in wheat, rice, and other cereal grains

- Stimulates growth of beneficial bacteria

- Produces beneficial metabolites upon fermentation

How Prebiotics Work

When you consume prebiotic fiber, it passes through the upper digestive tract undigested. In the colon, your beneficial bacteria ferment these fibers, producing[6]:

- Butyrate: The primary energy source for colon cells, reduces inflammation

- Propionate: Involved in gluconeogenesis and appetite regulation

- Acetate: Provides energy and supports peripheral tissue metabolism

This fermentation process creates an acidic environment that:

- Favors beneficial bacteria over pathogens

- Enhances mineral absorption (calcium, magnesium)

- Supports healthy bowel movements

- Strengthens gut barrier function

The Critical Difference: Food vs. The Fed

The simplest way to understand the difference:

| Aspect | Probiotics | Prebiotics |

|---|---|---|

| What they are | Live beneficial microorganisms | Non-digestible food compounds |

| Origin | Fermented foods, supplements | Plant fibers, resistant starches |

| Function | Add beneficial bacteria to gut | Feed existing beneficial bacteria |

| Survival | Must survive stomach acid | Not affected by digestive processes |

| Storage | Often require refrigeration | Shelf-stable |

Why You Need Both: The Synbiotic Advantage

When probiotics and prebiotics are combined, they form what scientists call a "synbiotic"—a synergistic combination where the prebiotic supports the survival and activity of the probiotic[5].

Benefits of the Synbiotic Approach

Enhanced probiotic survival: Prebiotics provide fuel for probiotics during their journey through the digestive tract, improving colonization rates.

Amplified health effects: The combination often produces greater benefits than either component alone for:

- Digestive health

- Immune function

- Metabolic regulation

- Nutrient absorption

Sustained microbiome support: While probiotics provide immediate beneficial bacteria, prebiotics ensure long-term nourishment of your entire beneficial microbial community.

Prebiotics and Specific Health Conditions

Digestive Disorders

Research shows prebiotic supplementation can benefit various digestive conditions:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Low-dose prebiotics may reduce symptoms[7]

- Important to start slowly to minimize bloating

- Certain prebiotics better tolerated than others

- Butyrate-promoting prebiotics support intestinal healing

- May help maintain remission

- Consult healthcare provider for appropriate types and doses

Immune Health

Prebiotic fiber plays a crucial role in immune system function:

- Supports development of immune cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- Reduces systemic inflammation through SCFA production

- Enhances antibody responses to pathogens

- May reduce incidence of allergies and autoimmune conditions

Metabolic Health

For those working on metabolic goals, prebiotics offer significant benefits:

- Improve insulin sensitivity

- Support healthy weight management

- Lower LDL cholesterol (particularly beta-glucan)

- Regulate appetite through hormone modulation

How Much Do You Need?

Prebiotic Recommendations

Most research suggests consuming 5-15 grams of prebiotic fiber daily for health benefits[3]. However, the average Western diet provides only 1-4 grams.

Food sources and approximate content:

- 1 medium Jerusalem artichoke: 18g inulin

- 1 medium banana: 1-2g FOS

- 1/2 cup cooked oats: 2g beta-glucan

- 3 cloves garlic: 0.5g inulin/FOS

- 1/2 cup cooked lentils: 2-3g resistant starch

Important tip: Increase prebiotic intake gradually over 2-3 weeks to allow your microbiome to adapt and minimize digestive discomfort.

Probiotic Recommendations

Probiotic doses are measured in colony-forming units (CFUs). Effective doses typically range from 1 billion to 100 billion CFUs daily, depending on the condition and strain[4].

Key considerations:

- More CFUs isn't always better

- Strain specificity matters—different strains have different effects

- Quality and viability are crucial

- Consistency often matters more than dose

The Consequences of Prebiotic Deficiency

Modern diets often lack adequate prebiotic fiber, with significant consequences[8]:

- Mucus layer degradation: Without fiber, gut bacteria may begin consuming the protective mucus lining

- Increased permeability: "Leaky gut" can develop, allowing harmful substances to enter the bloodstream

- Reduced SCFA production: Less fuel for colon cells and decreased anti-inflammatory effects

- Pathogen susceptibility: Weakened defenses against harmful bacteria

Practical Guide: Optimizing Your Prebiotic and Probiotic Intake

Daily Meal Ideas

Breakfast:

- Overnight oats (beta-glucan) with banana (FOS) and kefir (probiotics)

- Whole grain toast with avocado and sauerkraut

Lunch:

- Large mixed salad with onions, garlic (prebiotics) and kimchi (probiotics)

- Lentil soup (resistant starch) with whole grain bread

Dinner:

- Roasted vegetables including Jerusalem artichokes, leeks, asparagus (inulin, FOS)

- Miso-glazed salmon with quinoa

Snacks:

- Apple slices (pectin) with yogurt (probiotics)

- Hummus with raw vegetables (chicory root fiber)

Supplement Considerations

If you choose to supplement, look for:

Prebiotic supplements:

- Inulin or FOS for general microbiome support

- Resistant starch for butyrate production

- Acacia fiber for gentle, well-tolerated supplementation

- GOS for targeted Bifidobacterium support

Probiotic supplements:

- Multi-strain formulations for general health

- Condition-specific strains when addressing particular issues

- Products with demonstrated stability and viability

- Reputable manufacturers with third-party testing

Who Should Be Cautious?

While prebiotics and probiotics are generally safe, certain individuals should consult healthcare providers:

- Those with SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth)

- Immunocompromised individuals

- People with severe digestive conditions

- Those taking immunosuppressive medications

- Individuals with central venous catheters (for certain probiotics)

Testing Your Microbiome Response

Want to know if your prebiotic and probiotic efforts are working? Microbiome testing can reveal:

- Changes in beneficial bacteria populations

- Diversity improvements

- SCFA production capacity

- Reduction in potentially harmful organisms

Baseline testing before interventions and follow-up testing after 2-3 months provides valuable feedback for optimizing your approach.

Conclusion

Prebiotics and probiotics represent two complementary strategies for supporting gut health. While probiotics introduce beneficial microorganisms directly, prebiotics nourish the trillions of helpful bacteria already residing in your gut. The most effective approach typically combines both—either through a diverse, whole-foods diet or strategic supplementation.

By understanding how these compounds work together, you can make informed choices to support your digestive health, strengthen your immune system, and optimize your overall wellbeing.

Explore our comprehensive prebiotics database to learn more about specific prebiotic fibers, or browse our microbiome database to discover the beneficial bacteria these fibers support.

References

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al.. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;14(8):491-502. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

- Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al.. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2014;11(8):506-514. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

- Slavin J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417-1435. doi:10.3390/nu5041417

- Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E, Elinav E. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nature Medicine. 2019;25(5):716-729. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0439-x

- Swanson KS, Gibson GR, Hutkins R, et al.. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2020;17(11):687-701. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0344-2

- Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Bäckhed F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host & Microbe. 2018;23(6):705-715. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

- Sanders ME, Merenstein DJ, Reid G, et al.. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019;16(10):605-616. doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0173-3

- Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, et al.. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167(5):1339-1353. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043