Opportunistic Bacteria: The Context-Dependent Microbes in Your Gut

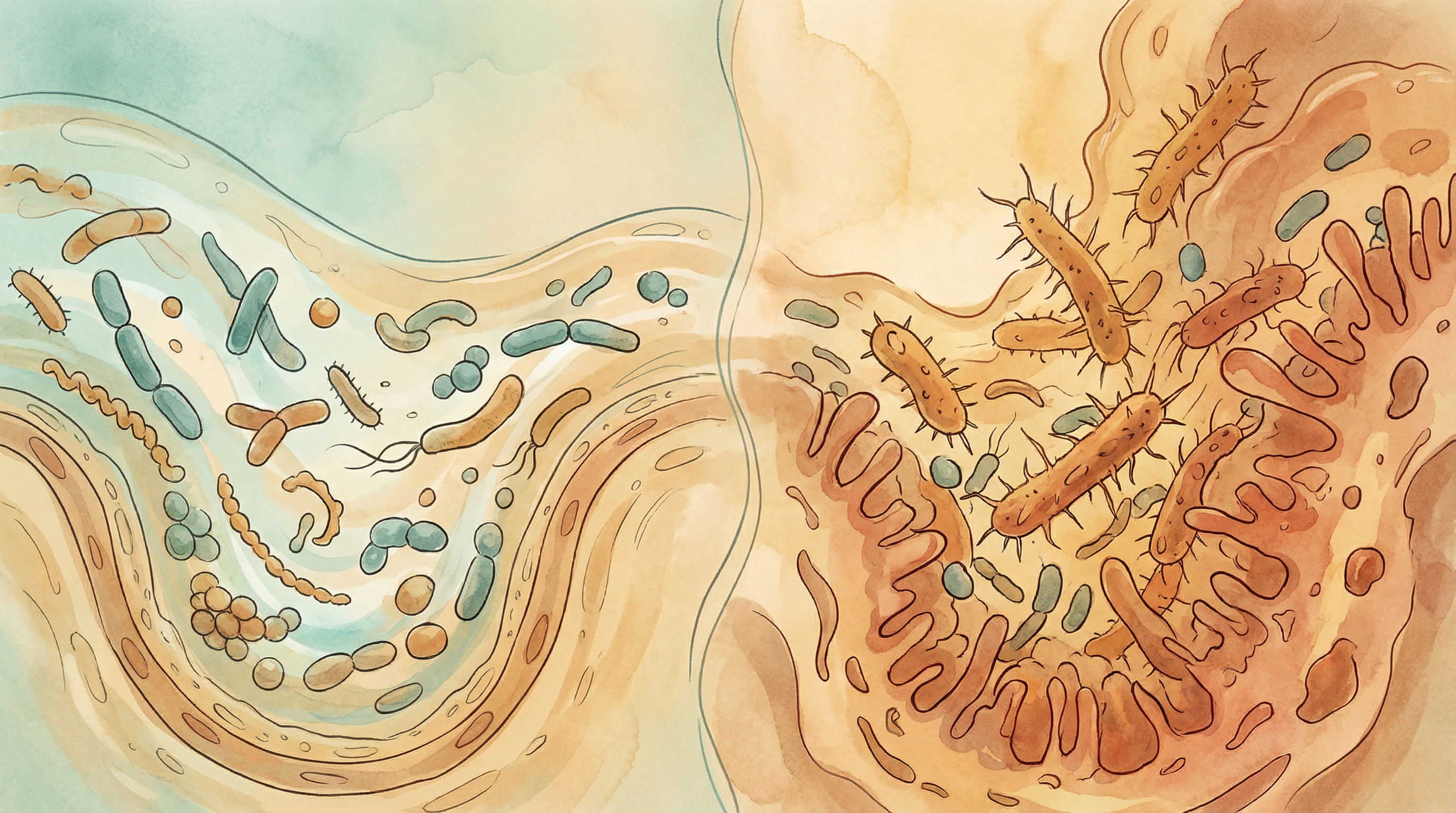

Not all gut bacteria fit neatly into "good" or "bad" categories. Many microorganisms are opportunistic—neutral or even beneficial under normal conditions but capable of causing problems when circumstances change. Understanding these context-dependent bacteria helps explain how gut health can shift from balance to dysbiosis[1].

What Are Opportunistic Bacteria?

Opportunistic bacteria (also called pathobionts) are microorganisms that[2]:

- Normally coexist peacefully with beneficial bacteria

- May provide benefits under certain conditions

- Can cause disease when the host's defenses are compromised

- Exploit disrupted ecosystems when microbial balance is disturbed

- Respond to environmental changes in the gut

This dual nature makes them particularly important to understand—they're part of the healthy microbiome, but their behavior depends entirely on context.

Key Examples of Opportunistic Bacteria

Escherichia coli (Non-Pathogenic Strains)

Most E. coli strains are commensals, not pathogens[4]:

Normal roles:

- Vitamin K production

- Competitive exclusion of pathogens

- Present in nearly all human guts

Opportunistic behavior:

- Can cause urinary tract infections (UTIs) if they travel to the bladder

- May overgrow during inflammation, worsening gut symptoms

- Certain strains thrive on inflammation byproducts

- Can become problematic in immunocompromised individuals

Context matters: E. coli illustrates the importance of location—harmless in the gut, but potentially dangerous elsewhere in the body.

Enterococcus Species

Common gut inhabitants with dual personalities:

Normal roles:

- Part of the healthy gut microbiome

- May support immune development

- Present in many fermented foods

Opportunistic behavior:

- Leading cause of hospital-acquired infections

- Naturally resistant to many antibiotics

- Can cause bloodstream infections in vulnerable patients

- Problematic when gut barrier is compromised

Klebsiella pneumoniae

A bacterium that demonstrates context-dependence clearly:

Normal presence:

- Found in healthy guts at low levels

- Usually kept in check by other bacteria

- May have some beneficial functions

Opportunistic behavior:

- Causes pneumonia, UTIs, and bloodstream infections

- Increasingly antibiotic-resistant

- Thrives when beneficial bacteria are depleted

- Associated with liver disease and alcohol use

Candida albicans

A fungal example of opportunism:

Normal presence:

- Part of many people's normal gut flora

- Kept in check by beneficial bacteria

- Low levels typically harmless

Opportunistic behavior:

- Causes candidiasis when overgrown

- Exploits antibiotic-disrupted microbiomes

- Problematic in immunocompromised individuals

- Can penetrate gut barrier when conditions favor it

Bacteroides fragilis

Shows both beneficial and harmful potential:

Beneficial roles:

- Important for immune system development

- Produces anti-inflammatory polysaccharides

- Supports gut barrier function

Opportunistic behavior:

- Can cause abscesses if it escapes the gut

- Certain toxin-producing strains linked to colon cancer

- May contribute to inflammation in some contexts

Clostridium perfringens

Common but potentially dangerous:

Normal presence:

- Found in many healthy guts

- Usually at low, controlled levels

- Part of normal microbial community

Opportunistic behavior:

- Causes food poisoning when ingested in large numbers

- Can cause gas gangrene in wound infections

- Produces various toxins

- Thrives when microbiome is disrupted

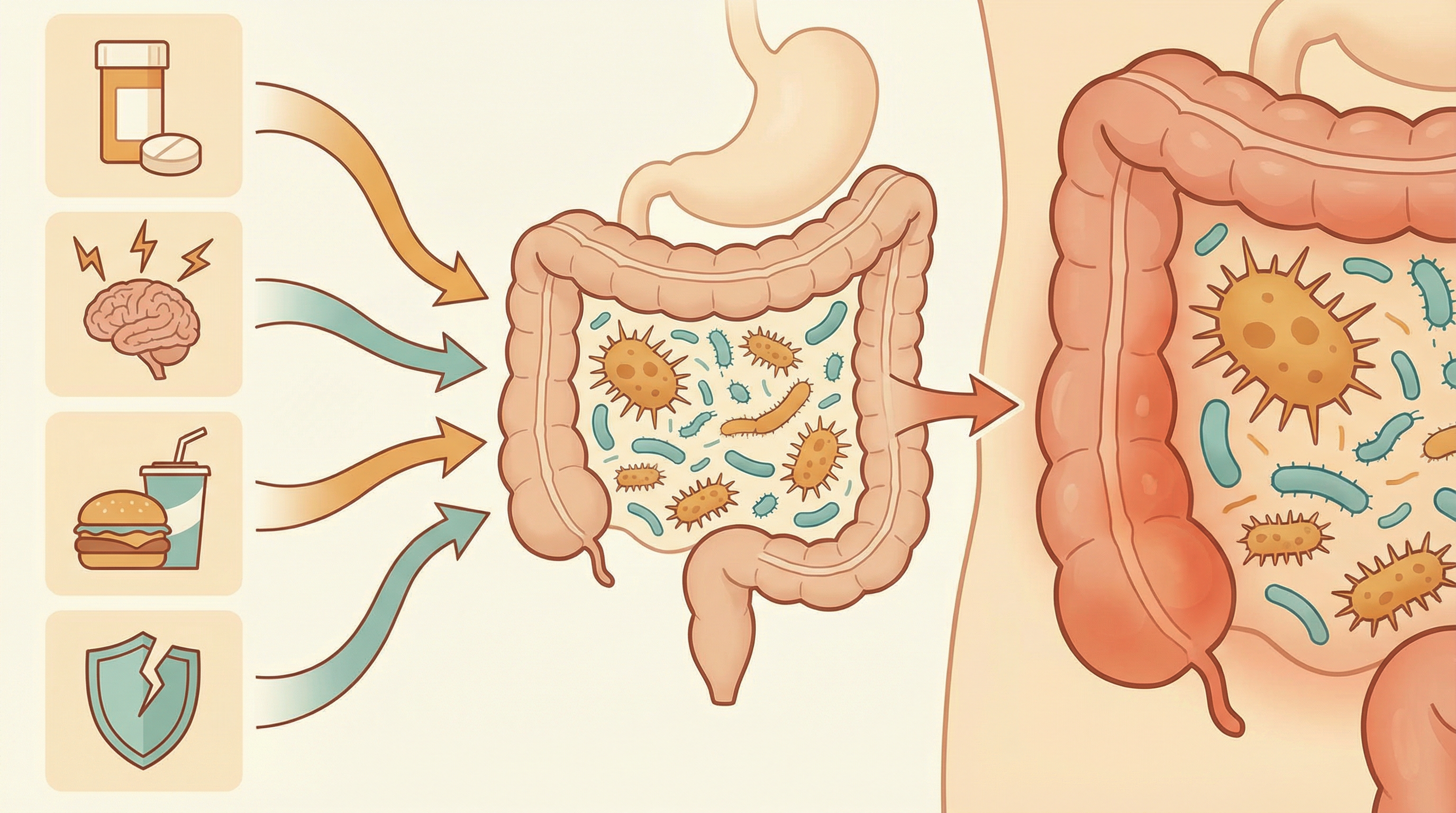

What Triggers Opportunistic Behavior?

1. Antibiotic Disruption

Antibiotics are the most common trigger[1]:

- Kill beneficial bacteria that normally compete with opportunists

- Create ecological vacuums that opportunists fill

- Reduce production of protective metabolites

- Allow resistant opportunistic strains to dominate

2. Immune Compromise

When host defenses weaken:

- Chemotherapy patients

- HIV/AIDS

- Transplant recipients on immunosuppressants

- Elderly with immune senescence

- Malnutrition or chronic illness

3. Inflammation

Inflamed gut environments favor opportunists[4]:

- Inflammation produces molecules some opportunists use as fuel

- Damages gut barrier, allowing bacterial translocation

- Reduces beneficial bacteria that control opportunists

- Creates oxidative stress that some pathogens tolerate better

4. Diet Changes

Dietary shifts can alter the balance:

- Low-fiber diets reduce beneficial bacteria

- High-fat/high-sugar diets may favor certain opportunists

- Malnutrition weakens host defenses

- Rapid dietary changes can destabilize the ecosystem

5. Stress and Lifestyle

Modern lifestyle factors:

- Chronic stress alters gut motility and immunity

- Sleep disruption affects microbiome composition

- Excessive alcohol damages gut barrier

- Sedentary lifestyle associated with reduced diversity

The Keystone Pathogen Concept

Some opportunists act as "keystone pathogens"—species that cause disease not by sheer numbers but by disrupting the entire microbial community[3]:

Characteristics:

- Can remodel microbial communities

- May lower colonization resistance

- Often trigger inflammatory responses

- Enable other opportunists to flourish

Example: Porphyromonas gingivalis (oral) This oral bacterium illustrates the concept—even at low levels, it can transform a healthy oral microbiome into a disease-promoting one by altering host immune responses and microbial interactions.

Health Conditions Associated with Opportunist Overgrowth

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD involves complex opportunist dynamics:

- Increased Enterobacteriaceae (including E. coli)

- Reduced diversity of beneficial bacteria

- Debate over whether changes cause or result from inflammation

- Opportunists may perpetuate disease cycles

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO represents opportunistic colonization of the wrong location:

- Bacteria that belong in the colon migrate to small intestine

- Causes bloating, diarrhea, malabsorption

- Often involves opportunistic species

- Structural or motility issues create permissive environment

Post-Antibiotic Complications

Common opportunist-related issues after antibiotics:

- Clostridioides difficile infection

- Fungal overgrowth (candidiasis)

- Increased susceptibility to other infections

- Altered metabolic function

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Changes in opportunist populations linked to metabolic health:

- Altered Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratios

- Changes in metabolite production

- Increased gut permeability

- Low-grade inflammation

Maintaining Balance: Keeping Opportunists in Check

Support Your Beneficial Bacteria

A healthy microbiome naturally controls opportunists:

Feed good bacteria:

- Prebiotic fibers (inulin, FOS, resistant starch)

- Diverse plant foods (30+ weekly)

- Fermented foods with live cultures

- Polyphenol-rich foods (berries, green tea)

Avoid unnecessary disruption:

- Use antibiotics only when truly needed

- Limit antimicrobial products in daily life

- Reduce processed food additives

- Minimize unnecessary medications

Strengthen Your Gut Barrier

Healthy barriers prevent opportunists from causing harm[2]:

Barrier support:

- Butyrate-producing foods (fiber fermentation)

- Adequate zinc intake

- Vitamin A sufficiency

- Glutamine-rich foods

- Stress management

Support Your Immune System

Competent immunity keeps opportunists controlled:

Immune support:

- Adequate sleep (7-9 hours)

- Regular moderate exercise

- Stress reduction practices

- Balanced nutrition

- Vitamin D sufficiency

Know Your Risk Factors

Be vigilant when risk increases:

Higher risk periods:

- During and after antibiotic treatment

- During high-stress periods

- When traveling (new microbial exposures)

- During immunosuppressive treatments

- As you age

Testing for Opportunist Overgrowth

Microbiome testing can identify concerning patterns[5]:

What testing shows:

- Relative abundance of different species

- Diversity measures

- Potential dysbiosis markers

- Comparison to healthy populations

Interpreting results:

- Presence of opportunists is normal

- Overgrowth or dominance is concerning

- Context (symptoms, history) matters

- Single tests are snapshots, not complete pictures

Limitations:

- Normal ranges vary widely

- Function matters more than presence

- Testing can't predict future behavior

- Should guide, not dictate, interventions

When to Seek Medical Help

Consult healthcare providers if you experience:

- Persistent digestive symptoms after antibiotics

- Recurring infections

- Symptoms suggesting C. difficile infection

- Signs of fungal overgrowth

- Unexplained digestive issues with risk factors

Conclusion

Opportunistic bacteria remind us that the microbiome operates as an ecosystem, not a collection of isolated good or bad actors. Context—your immune status, microbial diversity, gut barrier integrity, and lifestyle—determines whether these microorganisms remain peaceful cohabitants or become problematic.

By understanding what triggers opportunistic behavior, you can take proactive steps:

- Maintain a diverse, fiber-rich diet

- Avoid unnecessary microbiome disruption

- Support immune function

- Address underlying health conditions

- Seek care when warning signs appear

Your goal isn't to eliminate opportunists (that's neither possible nor desirable) but to maintain the conditions that keep them in check—a thriving ecosystem of beneficial bacteria, healthy gut barriers, and competent immune defenses.

Continue learning: Explore beneficial bacteria that help control opportunists, understand pathogenic bacteria that always cause harm, or browse our complete microbiome database to learn about specific species.

References

- Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2017;17(4):219-232. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.7

- Kamada N, Seo SU, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(5):321-335. doi:10.1038/nri3430

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(10):717-725. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2873

- Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, et al.. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science. 2013;339(6120):708-711. doi:10.1126/science.1232467

- Almeida A, Mitchell AL, Boland M, et al.. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2019;568(7753):499-504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1