How Your Gut Microbiome Shapes Your Immune System: The Science of Gut Immunity

The phrase "70% of your immune system is in your gut" has become a common refrain in health discussions. While this figure is an approximation, the underlying science is profound: your gut microbiome plays an essential role in developing, training, and regulating immune function throughout life[1].

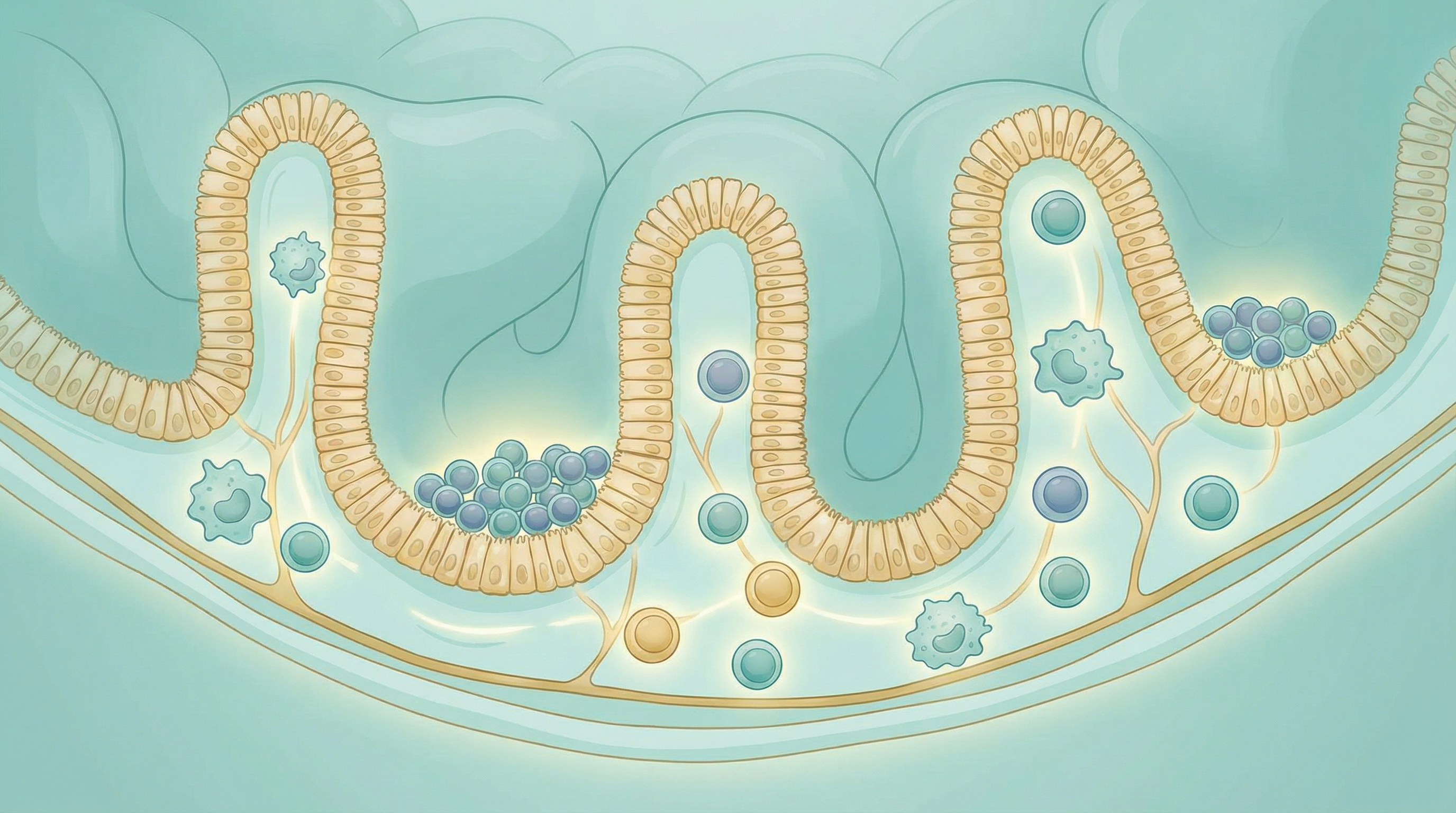

The Gut: Your Largest Immune Organ

Your gastrointestinal tract houses the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), the body's largest collection of immune cells. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective—the gut is the primary interface between your internal environment and the external world of food, microbes, and potential pathogens[2].

Key Immune Structures in the Gut

Peyer's patches: Clusters of lymphoid tissue in the small intestine that sample antigens from the gut lumen and initiate immune responses.

Mesenteric lymph nodes: Process antigens from the gut and generate appropriate immune responses.

Intestinal epithelial cells: Form a barrier while also producing antimicrobial peptides and communicating with immune cells.

Lamina propria: The tissue layer beneath the epithelium, densely populated with immune cells including T cells, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

How Gut Bacteria Train Your Immune System

From birth, gut microorganisms play a crucial role in educating the immune system[3]. This training process involves:

Early Life Programming

The immune system of newborns is essentially naive. Colonization by gut bacteria during the first years of life is critical for:

- Developing immune tolerance: Learning not to overreact to harmless substances

- Building defense capabilities: Preparing to fight actual pathogens

- Establishing the gut barrier: Creating a functional intestinal lining

Research shows that children born via cesarean section, who miss initial exposure to maternal vaginal and gut bacteria, have higher rates of allergies, asthma, and autoimmune conditions. Similarly, early antibiotic exposure can disrupt this critical training period.

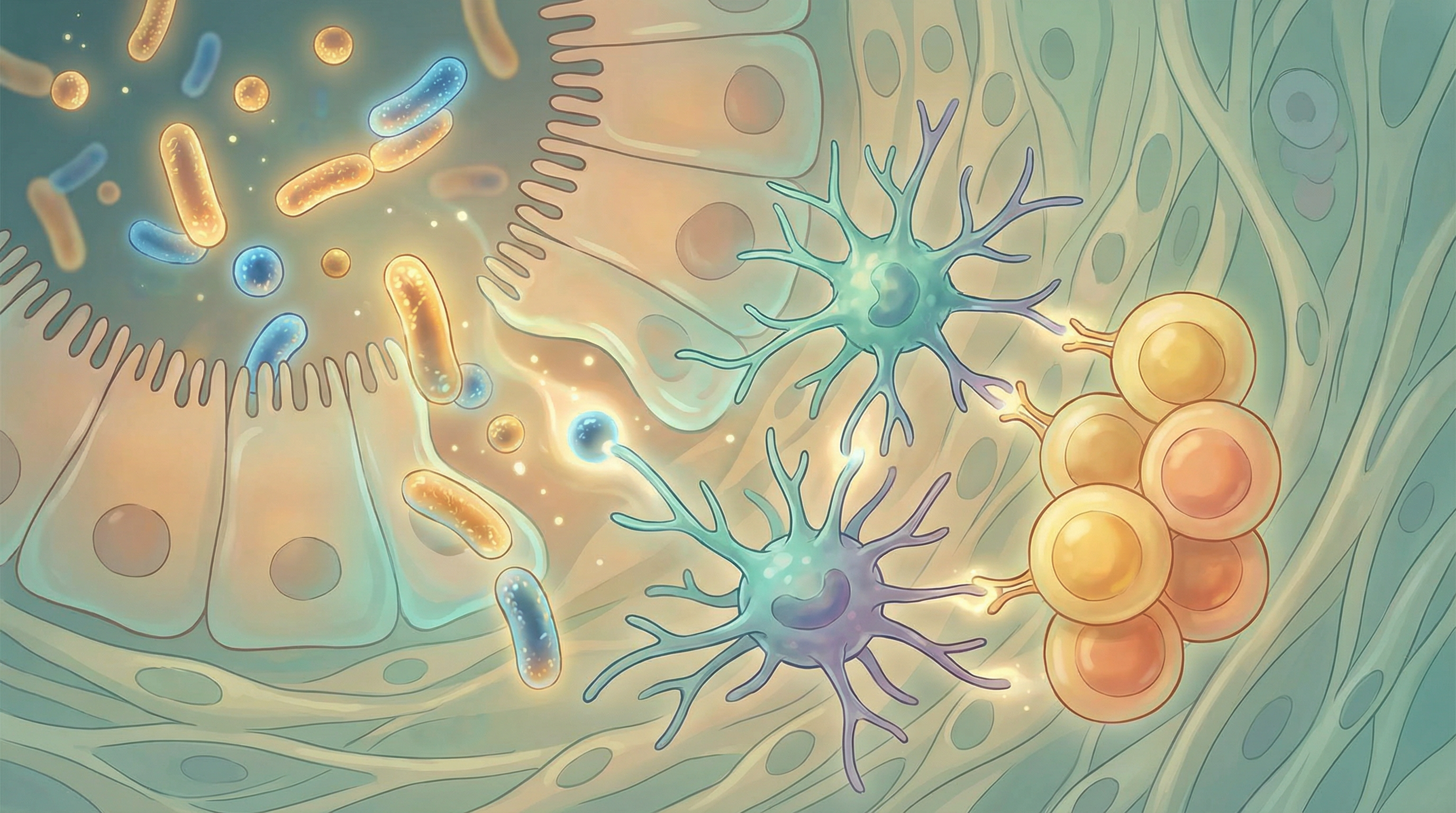

Continuous Immune Education

The microbiome continues to shape immunity throughout life. Beneficial bacteria constantly communicate with immune cells through:

- Pattern recognition: Immune cells recognize microbial molecular patterns

- Metabolite signaling: Bacterial products directly influence immune cell behavior

- Direct cell contact: Some bacteria interact directly with immune cells

Key Microbiome-Immune Interactions

Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Immune Modulators

When gut bacteria ferment prebiotic fibers, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—particularly butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These metabolites profoundly influence immune function[4]:

- Promotes development of regulatory T cells (Tregs) that prevent autoimmunity[5]

- Reduces inflammatory signaling in macrophages

- Strengthens the gut barrier, preventing immune activation by gut contents

- Enhances antimicrobial peptide production

- Modulates dendritic cell function

- Influences T helper cell differentiation

- Supports regulatory T cell generation

- Enhances antibody production by B cells

- Supports gut barrier integrity

- Provides energy for peripheral tissues involved in immunity

Specific Bacteria and Immune Regulation

Research has identified particular microorganisms with significant immune-modulating effects[6]:

- One of the most abundant gut bacteria in healthy individuals

- Major butyrate producer

- Has strong anti-inflammatory properties

- Reduced levels associated with IBD and other inflammatory conditions

- Lives in the mucus layer lining the gut

- Strengthens gut barrier function

- Associated with reduced inflammation

- May protect against metabolic disorders

- Produce acetate and lactate

- Enhance antibody responses to pathogens

- Support infant immune development

- May reduce allergic responses

- Modulate dendritic cell function

- Enhance mucosal immunity

- Produce antimicrobial substances

- Support balanced T helper cell responses

Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa:

- Potent inducers of regulatory T cells

- Critical for preventing intestinal inflammation

- Reduced in many autoimmune conditions

The Balance: Immunity Without Inflammation

The immune system faces a constant challenge: it must respond vigorously to dangerous pathogens while tolerating beneficial microbes and harmless food antigens. This balance is maintained through several mechanisms[7]:

Regulatory T Cells (Tregs)

These specialized immune cells act as "peacekeepers," preventing excessive immune responses. Gut bacteria—particularly through SCFA production—are essential for generating adequate Treg populations.

Insufficient Tregs can lead to:

- Inflammatory bowel diseases

- Food allergies and intolerances

- Autoimmune conditions

- Chronic systemic inflammation

The Mucosal Firewall

The gut maintains multiple layers of protection that keep the immune system from overreacting:

- Mucus layer: Physical barrier keeping bacteria away from epithelial cells

- Secretory IgA: Antibodies that neutralize pathogens without triggering inflammation

- Antimicrobial peptides: Proteins that kill harmful bacteria while sparing commensals

- Tight junctions: Seal between epithelial cells, preventing leakage

When the System Breaks Down: Dysbiosis and Disease

Disruption of the gut microbiome—known as dysbiosis—can trigger or worsen immune-related conditions[8]:

Allergies and Atopic Conditions

The "hygiene hypothesis" suggests that reduced microbial exposure contributes to the rising prevalence of allergies. Specific microbiome patterns associated with allergic disease include:

- Reduced diversity in early life

- Lower abundance of Bifidobacterium and certain Clostridia

- Altered SCFA production

- Impaired Treg development

Microbiome-targeted interventions show promise for allergy prevention and treatment, particularly when initiated early in life.

Autoimmune Diseases

Multiple autoimmune conditions show characteristic microbiome alterations:

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD):

- Reduced Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

- Decreased microbial diversity

- Increased potentially pathogenic bacteria

- Impaired butyrate production

- Altered Prevotella levels

- Reduced beneficial Bifidobacterium

- Gut inflammation preceding joint symptoms

Type 1 Diabetes:

- Reduced microbial diversity before disease onset

- Altered SCFA-producing bacteria

- Potential role in triggering autoimmune attack on pancreatic cells

Multiple Sclerosis:

- Distinct microbiome signatures

- Potential gut-brain-immune axis involvement

- Ongoing research into microbiome-based therapies

Chronic Inflammation

Even without specific autoimmune disease, dysbiosis can promote low-grade systemic inflammation—now recognized as a driver of numerous chronic conditions including:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Metabolic syndrome

- Neurodegenerative diseases

- Certain cancers

- Accelerated aging

Supporting Immune Health Through the Microbiome

Understanding gut-immune connections opens powerful opportunities for supporting immune health:

Dietary Strategies

Increase prebiotic fiber intake:

- Inulin from chicory root, garlic, onions

- Beta-glucan from oats, mushrooms

- Resistant starch from cooled potatoes, green bananas

- Pectin from apples, citrus fruits

Consume fermented foods:

- Yogurt with live cultures

- Kefir

- Sauerkraut and kimchi

- Miso and tempeh

Eat polyphenol-rich foods:

- Berries, grapes, cocoa

- Green tea, coffee

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Colorful vegetables

Limit immune-disrupting foods:

- Ultra-processed foods with emulsifiers

- Excessive sugar

- Artificial sweeteners (may alter microbiome)

- Excessive alcohol

Targeted Probiotic Supplementation

For immune support, research suggests particular strains may be beneficial:

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: Reduces infection duration, supports gut barrier

- Bifidobacterium lactis: Enhances immune cell activity

- Lactobacillus acidophilus: Supports mucosal immunity

- Saccharomyces boulardii: Protects against pathogenic bacteria

Always choose probiotics with demonstrated efficacy for your specific goal, and consult healthcare providers for personalized recommendations.

Lifestyle Factors

Manage stress: Chronic stress alters microbiome composition and immune function through the gut-brain axis. Practices like meditation, yoga, and adequate rest support both microbiome and immune health.

Exercise regularly: Moderate exercise increases microbial diversity and supports immune function. Extreme exercise, however, can temporarily suppress immunity.

Prioritize sleep: Disrupted sleep patterns alter the microbiome and impair immune responses. Aim for consistent sleep-wake cycles and 7-9 hours nightly.

Minimize unnecessary antibiotics: While sometimes essential, antibiotics can significantly disrupt the microbiome. When antibiotics are necessary, supporting microbiome recovery afterward is crucial.

Testing and Personalization

Microbiome testing can provide insights into your gut-immune connection:

What testing can reveal:

- Microbial diversity (correlates with immune health)

- Levels of key immune-modulating bacteria

- SCFA production capacity

- Potential dysbiosis patterns

Limitations to understand:

- Testing provides a snapshot, not continuous data

- Normal ranges vary significantly between individuals

- Direct causation is difficult to establish

- Results should be interpreted with professional guidance

The Future of Microbiome-Based Immunotherapy

Exciting research directions include:

- Precision probiotics: Engineered strains designed to modulate specific immune pathways

- Postbiotics: Defined bacterial metabolites used therapeutically

- Fecal microbiota transplantation: For severe dysbiosis and immune conditions

- Microbiome-informed drug development: Medications that work synergistically with gut bacteria

Conclusion

The gut microbiome represents a powerful lever for influencing immune function. From early life development through ongoing immune regulation, the bacteria residing in your digestive system profoundly shape how your body responds to threats while maintaining tolerance to beneficial substances.

By nurturing a diverse, balanced microbiome through diet, lifestyle, and targeted interventions, you can support robust immune function while reducing the risk of allergic and autoimmune conditions.

Whether you're looking to strengthen defenses against infections, manage an existing immune condition, or optimize overall health, attending to your gut microbiome is an evidence-based strategy with far-reaching benefits.

Explore our immunity health goal for more strategies, or learn about specific conditions where microbiome interventions show promise. Consider microbiome testing to understand your personal gut-immune landscape and develop targeted interventions.

References

- Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121-141. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011

- Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Research. 2020;30(6):492-506. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7

- Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2016;535(7610):75-84. doi:10.1038/nature18848

- Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2016;16(6):341-352. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.42

- Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, et al.. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451-455. doi:10.1038/nature12726

- Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, et al.. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500(7461):232-236. doi:10.1038/nature12331

- Blander JM, Longman RS, Iliev ID, et al.. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nature Immunology. 2017;18(8):851-860. doi:10.1038/ni.3780

- Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2017;17(4):219-232. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.7