Enterococcus faecalis

Overview

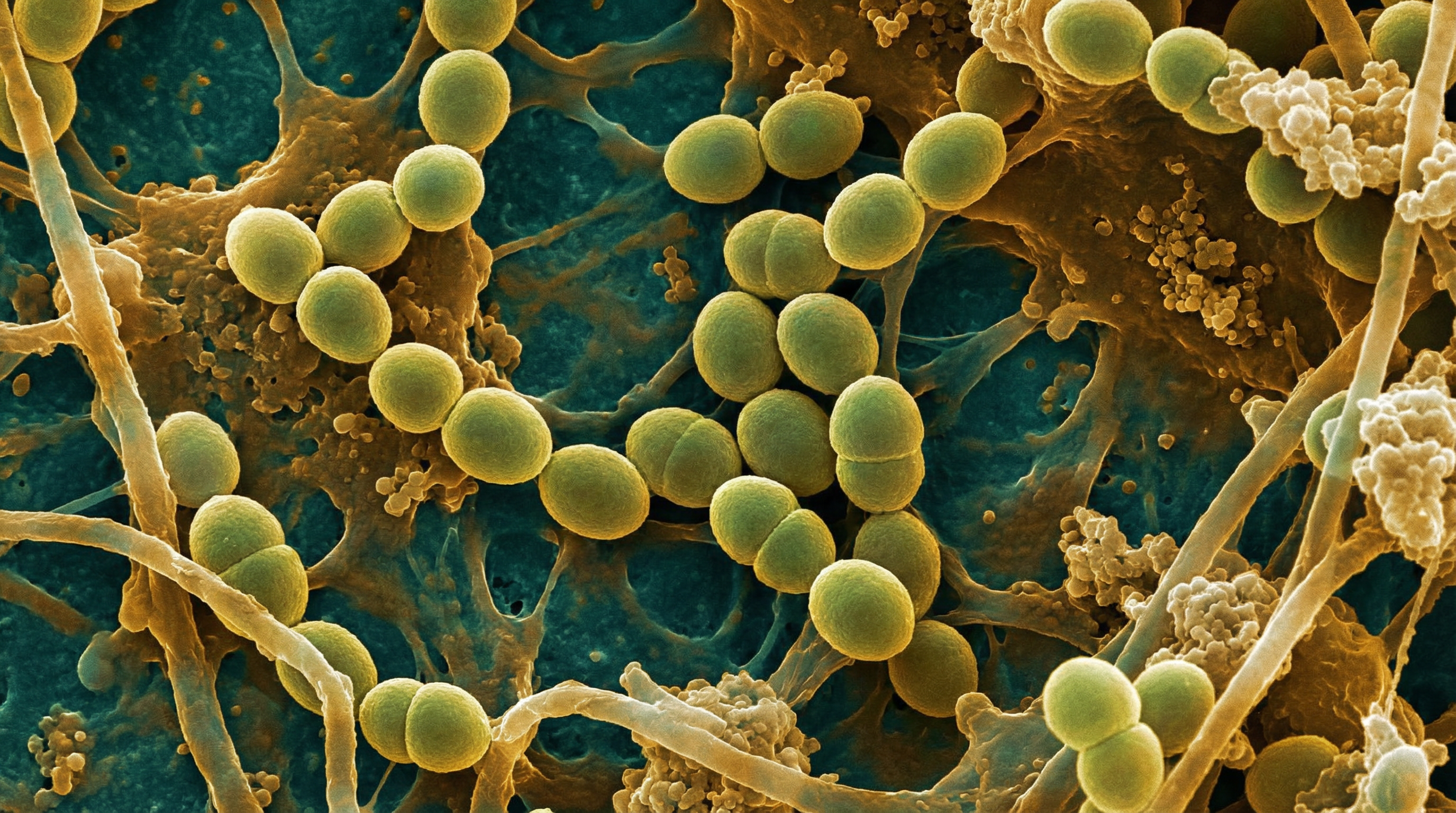

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacterium that exhibits a remarkable dual nature as both a commensal organism and an opportunistic pathogen. While representing less than 1% of normal gut microbiota, E. faecalis has emerged as the second most common cause of healthcare-associated infections in the United States and Europe, responsible for 60-80% of all enterococcal infections.

Intriguingly, molecular dating reveals that hospital-adapted E. faecalis lineages emerged between 1846-1967, predating the modern hospital era and antibiotic era—suggesting that factors other than antibiotic selection drove their initial emergence.

Key Characteristics

E. faecalis typically appears in pairs (diplococci) or short chains. It is non-motile and non-spore-forming, with an oval shape. This bacterium demonstrates remarkable environmental hardiness:

- Temperature tolerance: Growth from 10°C to 45°C (optimum 35°C)

- pH tolerance: pH 4.4 to 9.6

- Salt tolerance: Up to 6.5% NaCl

- Bile tolerance: Hydrolyzes esculin in 40% bile salts

- Surface persistence: Survives up to 4 months on environmental surfaces; 60 minutes on hands

The genome shows extraordinary plasticity, with only 13.1% representing core genome (2,068/15,827 genes) and up to 25% being exogenously acquired DNA.

Role in Human Microbiome

Normal Abundance

In healthy individuals, E. faecalis represents a subdominant member of the gut microbiota:

- Proportion: 0.1-1% of total fecal microbiota

- Population density: 10⁵-10⁷ CFU/g feces

- Total intestinal count: 10⁶ to 10⁷ bacteria

Beneficial Functions

As a commensal, E. faecalis contributes to gut homeostasis through:

- Nutrient metabolism (carbohydrates, lipids, proteins)

- pH maintenance via lactic acid production

- Vitamin synthesis

- Immunomodulation (activation of CD4, CD8, B lymphocytes)

- Secretory IgA (sIgA) production

- Colonization resistance via bacteriocins

Colonization Resistance

E. faecalis produces antimicrobial bacteriocins that inhibit competing bacteria, including VRE and pathogens. This colonization resistance is disrupted by:

- Antibiotic depletion of competing anaerobes

- Loss of obligate anaerobes (Barnsiella, Clostridium cluster XIVa, Blautia producta)

- Reduced RegIIIγ production from loss of Gram-negative bacteria

Virulence Factors

E. faecalis possesses multiple virulence determinants that enable its pathogenic transition:

Adhesins

| Factor | Gene(s) | Prevalence | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregation substance | agg, asa1, asp1 | 33.3-69.2% | Bacterial aggregation, adherence to host cells |

| Enterococcal surface protein | esp | 70-70.1% | Initial adherence, biofilm formation |

| Collagen-binding protein | ace | 96.3% | Binds collagen types I/IV and fibrinogen |

| Cell wall adhesins | efaAfs | 76.9-100% | Tissue adherence |

| Endocarditis/biofilm pili | ebpA/B/C | 70.4-96.3% | Biofilm formation, endocarditis |

Gelatinase (GelE): A Key Immune Evasion Factor

Gelatinase is a 34 kDa extracellular metalloendopeptidase with profound effects on host immunity:

- Prevalence: Gene present in 73.3-100% of isolates; phenotype in 33.5-100%

- Complement evasion: Cleaves C3 and C3a complement alpha chains

- Inhibitory potency: >90% inhibition at concentrations >0.2 μM

- Survival effect: 30% serum pretreated with GelE results in 100% bacterial survival

- Antimicrobial peptide destruction: Degrades insect cecropins and host defense peptides

- Tissue invasion: Hydrolyzes collagen, casein, hemoglobin

Biofilm Formation

E. faecalis demonstrates exceptional biofilm-forming capacity:

- Prevalence: 87.3% of isolates form biofilms

- Strong-to-moderate formers: 70.4-75.4%

- Significant correlations: pil gene (p=0.03010), cell surface hydrophobicity (p=0.00718)

Biofilm formation is critical for persistent infections, particularly on medical devices and in endocarditis.

Cytolysin

A toxin with dual bactericidal and cytolytic activities that lyses red and white blood cells. Present primarily in clinical isolates rather than commensals.

Clinical Infections

E. faecalis is responsible for diverse healthcare-associated infections:

Bloodstream Infections

- Proportion: 61.9% of enterococcal BSI (vs 38.1% E. faecium)

- Hospital-acquired rate: 52.5%

- Polymicrobial rate: 28.8%

- Primary sources: Urinary tract, endocarditis

- Patient characteristics: Median age 72 years; median Charlson Comorbidity Index 3

Mortality

| Setting | Mortality Rate |

|---|---|

| In-hospital (monomicrobial E. faecalis) | 20.4% |

| BSI-related | 13.9% |

| With care bundle | 20% |

| Without care bundle | 32% |

Independent Mortality Predictors

| Factor | Adjusted OR |

|---|---|

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.27 |

| SOFA score | 1.47 |

| Age | 1.06 |

| Urinary/biliary source (protective) | 0.29 |

Infective Endocarditis

E. faecalis is the third most common cause of native valve endocarditis:

- Historical cure rates: ~40% with penicillin alone; >70% with aminoglycoside synergy

- Relapse rate: 7-10%

- Cardiac surgery required: ~40% of cases

Antibiotic Resistance

Intrinsic Resistance

E. faecalis is naturally resistant to:

- Cephalosporins

- Low-level aminoglycosides

- Clindamycin

Acquired Resistance Rates

| Antibiotic | Resistance Rate |

|---|---|

| Tetracycline | 69.3% |

| Macrolides | 47.2% |

| Lincosamides | 99.3% |

| Aminoglycosides | 45.0% |

| Vancomycin | ~10% (up to 14% in nosocomial strains) |

Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecalis

While less common than in E. faecium, VRE E. faecalis infections are increasingly reported, with resistance rates reaching ~10% globally and up to 14% in some nosocomial settings.

Treatment Guidelines

Infective Endocarditis

First-line for susceptible strains:

- Ampicillin 2g IV every 4 hours + Gentamicin 3 mg/kg IV in 1-3 divided doses

- Duration: 4-6 weeks

- Nephrotoxicity: 23%

For high-level aminoglycoside resistance (HLAR) or renal impairment:

- Ampicillin 2g IV every 4 hours + Ceftriaxone 2g IV every 12 hours

- Duration: 6 weeks

- Cure rate in HLAR: 100%

- Nephrotoxicity: 0%

- In-hospital mortality: 22% (comparable to aminoglycoside regimen)

Uncomplicated Bacteremia

| Scenario | Treatment | Dose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Ampicillin | 1-2g IV q4-6h | 7-14 days |

| Penicillin allergy | Vancomycin | 15mg/kg IV q8h | 7-14 days |

| VRE | Daptomycin | 6-8 mg/kg IV daily | 14+ days |

| VRE alternative | Linezolid | 600mg IV q12h | 14+ days |

Urinary Tract Infections

- Ampicillin (high-dose 18-30 g/day IV) for susceptible isolates

- Nitrofurantoin 100mg PO BID for VRE UTI

- Fosfomycin 3g PO single dose for VRE UTI

Metabolic Activities

E. faecalis possesses versatile metabolic capabilities:

Bile Acid Metabolism

During eubiosis, E. faecalis contends with deoxycholate (DCA), which impairs growth by affecting ribosomal protein expression. During dysbiosis, increased taurocholate (TCA) activates oligopeptide permease systems and adjusts amino acid/nucleotide metabolism, potentially contributing to overgrowth.

Carbohydrate Fermentation

Uses Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway for glycolysis, producing lactic acid as the main end product (homofermentative).

Respiratory Metabolism

Although primarily fermentative, E. faecalis can engage in respiration when heme and electron acceptors are available, enhancing growth and survival.

Immune System Interactions

Innate Immunity

- TLR5 signaling: Flagellin triggers IL-23/IL-22 induction → RegIIIγ antimicrobial peptide production

- TLR2-MyD88 pathway: Critical for host containment; defects lead to impaired clearance

- Mucin secretion: MyD88-dependent stimulation of goblet cells maintains intestinal barrier

Adaptive Immunity

- Activates CD4, CD8, and B lymphocytes

- Stimulates secretory IgA production

- Modulates cytokines: IL-10 (via PPAR-γ1), TGF-β for colonic homeostasis

- Context-dependent pro-inflammatory (IL-6, TNF-α) or anti-inflammatory effects

Dysbiosis and Pathogenic Transition

The shift from commensal to pathogen involves:

- Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis: Depletion of competing anaerobes removes colonization resistance

- Population expansion: Can reach 10⁹ CFU/g (exceeding 30% relative abundance or 99% of intestinal lumen)

- Virulence gene acquisition: Horizontal gene transfer of pathogenicity islands

- Barrier translocation: Facilitated by Klebsiella pneumoniae and other factors

- Bloodstream invasion: Impaired complement and fucosylation enables dissemination

Infection Control

Given E. faecalis's persistence in healthcare environments:

- Environmental survival: Up to 4 months on surfaces

- Hand persistence: 60 minutes on skin

- ICU colonization rate: 33%

- Colonized-to-infected ratio: 10:1

Key infection control measures:

- Contact precautions for VRE patients

- Hand hygiene compliance

- Environmental cleaning protocols

- Antimicrobial stewardship to reduce selective pressure

Research Significance

E. faecalis serves as a model organism for studying:

- Host-pathogen relationships and commensal-to-pathogen transitions

- Horizontal gene transfer and antibiotic resistance evolution

- Biofilm biology and device-associated infections

- Bile acid interactions in gut ecology

- Potential probiotic/postbiotic applications (strain-specific)

Understanding E. faecalis biology is critical for developing new therapeutic strategies and infection prevention approaches in an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance.