Enhanced Epithelial Barrier

Strengthen your intestinal lining through microbiome optimization to prevent leaky gut, reduce inflammation, and improve overall digestive health.

Key Supporting Microbes

These beneficial microorganisms play key roles in supporting this health benefit:

Understanding the Epithelial Barrier

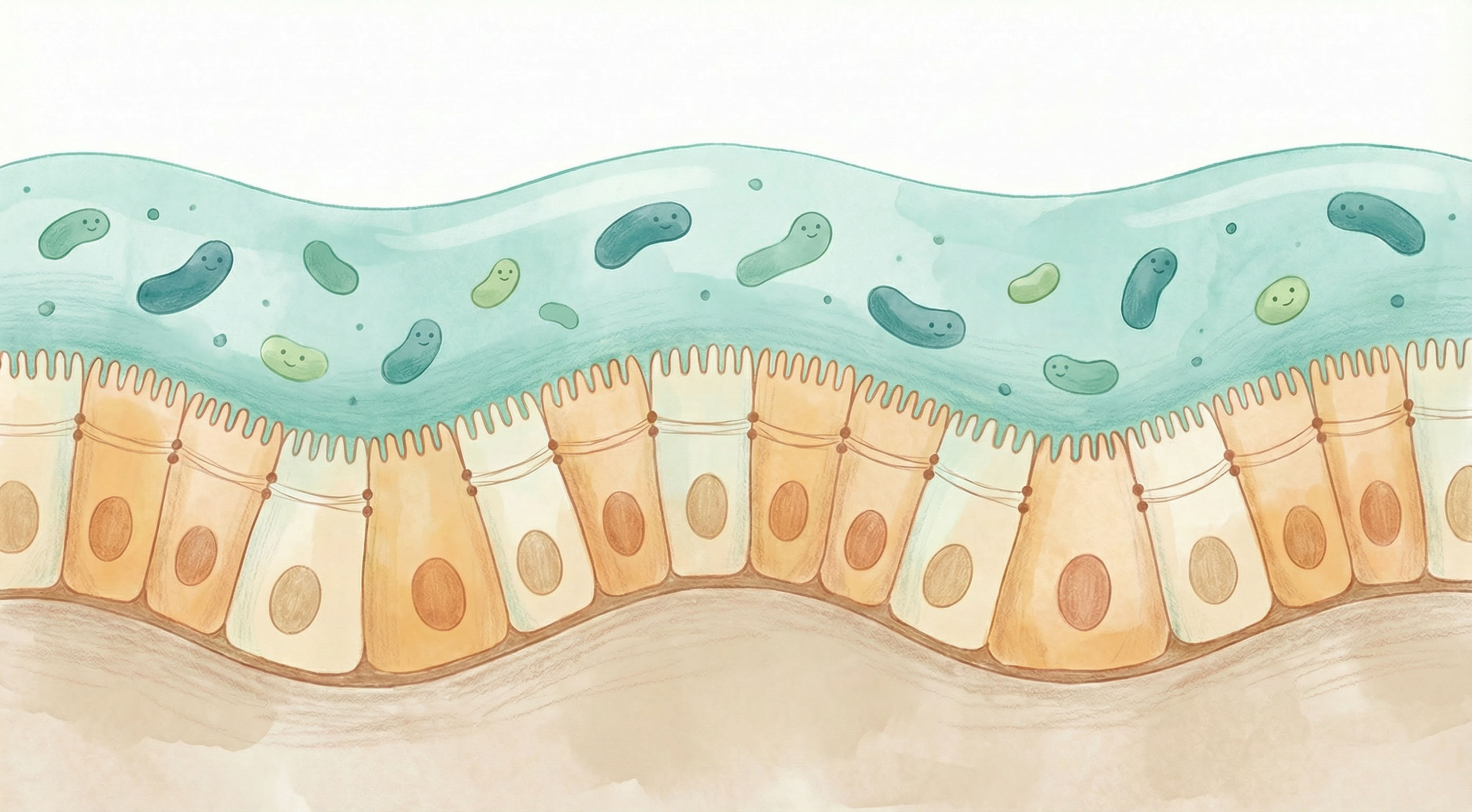

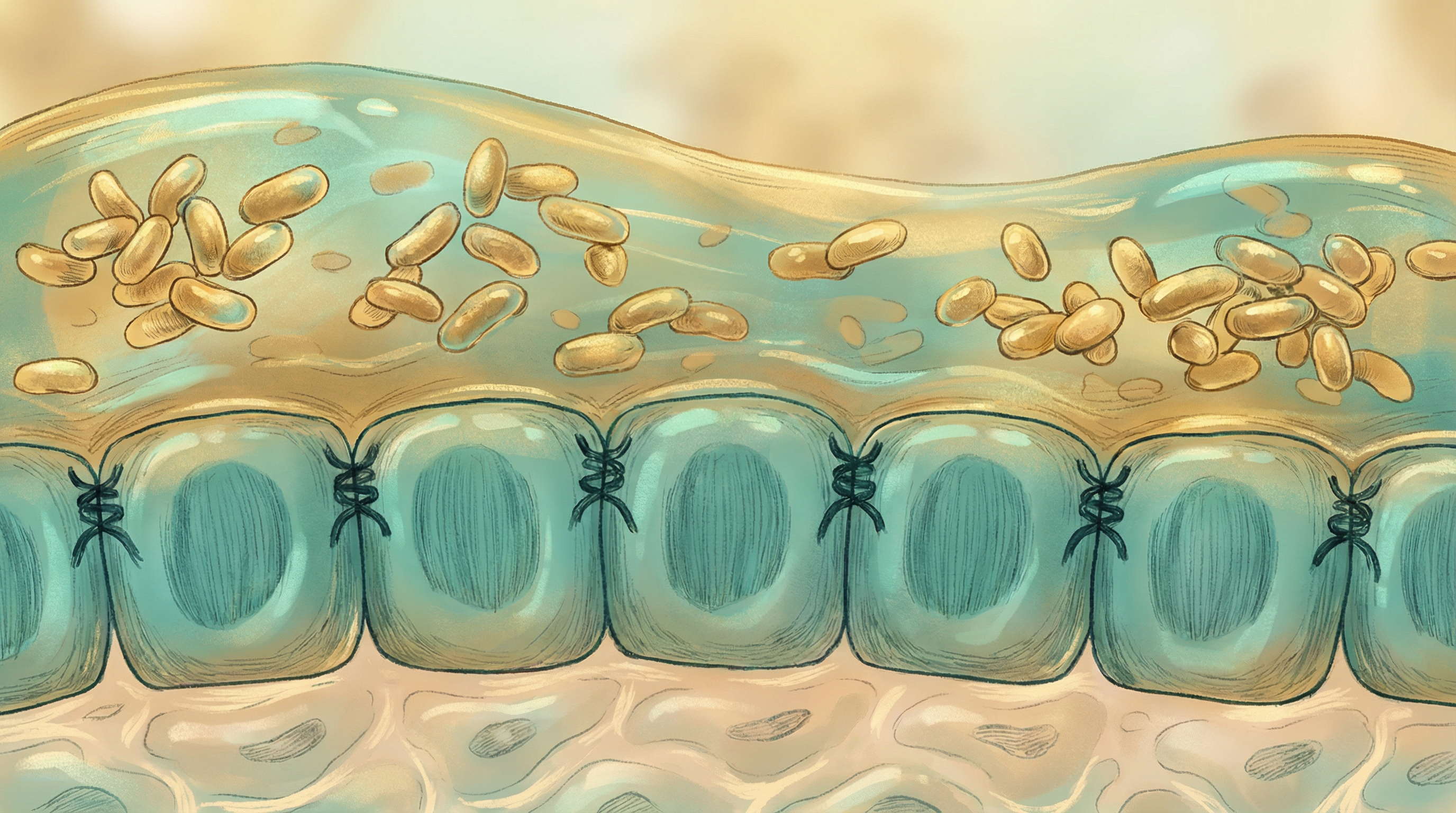

The intestinal epithelial barrier is a single layer of cells lining your digestive tract that serves as the critical interface between your body and the external environment. This barrier performs the delicate balancing act of allowing beneficial nutrients to pass through while blocking harmful substances like pathogens, toxins, and undigested food particles.[1]

When functioning optimally, this barrier maintains "selective permeability"—letting in what you need while keeping out what could harm you. However, when compromised, a condition often called "leaky gut" or increased intestinal permeability can develop, allowing substances to pass through that shouldn't.

The Microbiome's Role in Barrier Function

Your gut microbiome plays a fundamental role in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity through several mechanisms:[2]

Tight Junction Regulation

The cells of the intestinal lining are held together by protein complexes called tight junctions. Beneficial bacteria produce metabolites that strengthen these junctions:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate directly nourish epithelial cells and enhance tight junction protein expression

- Specific bacterial proteins can signal epithelial cells to reinforce their connections

- Reduced inflammation from a balanced microbiome prevents tight junction degradation

Mucus Layer Support

A healthy mucus layer sits above the epithelial cells, providing an additional protective barrier:

- Akkermansia muciniphila specializes in mucin degradation, which paradoxically stimulates the gut to produce more, fresher mucus[3]

- Beneficial bacteria produce signals that increase mucin gene expression

- A diverse microbiome prevents pathogenic bacteria from degrading the mucus layer

Antimicrobial Defense

Epithelial cells produce antimicrobial peptides that help control bacterial populations:

- Beneficial bacteria stimulate appropriate antimicrobial peptide production

- This helps prevent pathogenic overgrowth near the epithelial surface

- A balanced microbiome ensures this defense system remains calibrated

Key Beneficial Microbes

Akkermansia muciniphila

This mucin-degrading bacterium has emerged as a key player in barrier health. Research shows that A. muciniphila:

- Stimulates mucus production and turnover

- Produces proteins that directly strengthen the gut barrier

- Is associated with improved metabolic health markers

- May be reduced in conditions involving barrier dysfunction

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

As one of the most abundant bacteria in a healthy gut, F. prausnitzii:

- Produces significant amounts of butyrate, the primary fuel for colonocytes

- Has potent anti-inflammatory properties

- Is often depleted in inflammatory bowel conditions

- Supports epithelial cell health and regeneration

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Species

These traditional probiotics contribute to barrier function by:

- Producing lactic acid that creates an unfavorable environment for pathogens

- Competing with harmful bacteria for attachment sites on epithelial cells

- Modulating immune responses to reduce inflammation

- Producing bacteriocins that inhibit pathogenic bacteria

Signs of Compromised Barrier Function

Increased intestinal permeability may contribute to:

- Digestive symptoms like bloating, gas, and irregular bowel movements

- Food sensitivities that seem to be increasing

- Skin conditions like eczema or acne

- Fatigue and brain fog

- Joint pain and inflammation

- Autoimmune conditions

Dietary Strategies for Barrier Support

Foods to Emphasize

Polyphenol-rich foods support Akkermansia and other beneficial bacteria:

- Berries (especially blueberries and cranberries)

- Green tea and matcha

- Dark chocolate (70%+ cacao)

- Red grapes and pomegranates

Prebiotic fibers feed butyrate-producing bacteria:

- Cooked and cooled potatoes (resistant starch)

- Green bananas and plantains

- Jerusalem artichokes and chicory root

- Onions, garlic, and leeks

Fermented foods introduce beneficial bacteria:

- Yogurt with live cultures

- Kefir

- Sauerkraut and kimchi

- Miso and tempeh

Foods to Minimize

Certain foods and substances can damage the epithelial barrier:

- Excessive alcohol directly damages epithelial cells and disrupts tight junctions

- Processed foods high in emulsifiers may increase permeability

- Refined sugars can promote inflammatory bacterial species

- Frequent NSAID use compromises the protective mucus layer

Lifestyle Factors

Beyond diet, several lifestyle factors influence barrier integrity:

Stress Management

Chronic stress activates the HPA axis and increases cortisol, which:

- Reduces blood flow to the digestive tract

- Alters microbiome composition

- Directly increases intestinal permeability

Regular stress-reduction practices like meditation, deep breathing, or yoga can help maintain barrier function.

Sleep Quality

Poor sleep is associated with:

- Reduced microbial diversity

- Increased inflammatory markers

- Impaired epithelial cell regeneration

Prioritizing 7-9 hours of quality sleep supports gut barrier health.

Exercise

Moderate exercise has been shown to:

- Increase microbial diversity

- Boost butyrate-producing bacteria

- Reduce systemic inflammation

However, excessive intense exercise without adequate recovery can temporarily increase permeability.

Testing and Assessment

While there's no perfect test for intestinal permeability, several options exist:

- Lactulose-mannitol test: Measures the ratio of these sugars in urine after ingestion

- Zonulin levels: A protein associated with tight junction regulation

- Comprehensive stool testing: Can identify dysbiosis patterns associated with barrier dysfunction

- Inflammatory markers: Elevated markers may suggest barrier compromise

The Path Forward

Improving epithelial barrier function is a gradual process that involves:

- Addressing underlying causes like chronic stress, poor diet, or medication overuse

- Supporting beneficial bacteria through prebiotic and probiotic strategies

- Reducing inflammatory triggers in your diet and environment

- Giving your gut time to heal — epithelial cells renew every 4-5 days, but establishing a supportive microbiome takes longer

With consistent effort, most people can significantly improve their gut barrier function within 3-6 months, though benefits often begin to appear within weeks.

Supporting Practices

Evidence-based strategies to support this benefit:

- Consume polyphenol-rich foods (berries, green tea, dark chocolate)

- Include prebiotic fibers like inulin and resistant starch

- Avoid excessive alcohol and NSAIDs that damage the gut lining

- Manage stress through meditation or yoga

- Consider L-glutamine supplementation

- Eat fermented foods daily

References

- Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, et al.. Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterology. 2014;14:189. doi:10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7 ↩

- Chelakkot C, Ghim J, Ryu SH. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2018;50(8):1-9. doi:10.1038/s12276-018-0126-x ↩

- Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, et al.. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila improves gut barrier function. Nature Medicine. 2017;23(1):107-113. doi:10.1038/nm.4236 ↩