Haemophilus influenzae

Haemophilus influenzae is a pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacillus and a WHO priority pathogen requiring urgent new therapeutics due to rising antibiotic resistance[1]. In 2021, it caused 5.61 million cases and 175,000 deaths globally, with nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) responsible for 68.7% of cases and 75.8% of deaths[2]. Despite the remarkable success of Hib vaccination (90.3% reduction in pediatric mortality since 1990), the disease burden has shifted from young children toward neonates and older adults (≥70 years).

Key Characteristics

H. influenzae is a small, non-motile, facultatively anaerobic bacterium that requires special growth factors for cultivation. It is fastidious and requires both Factor X (hemin) and Factor V (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NAD) for growth. A critical 2025 study identified this haem-iron dependency as a therapeutic vulnerability—NTHi lacks enzymes for protoporphyrin IX biosynthesis, and loss of haem utilization protein SapF results in morphological plasticity and altered biofilm architecture[3].

The bacterium is divided into two major groups:

Encapsulated strains: These possess a polysaccharide capsule and are classified into six serotypes (a-f) based on the antigenic properties of their capsular polysaccharides. H. influenzae type b (Hib) is the most virulent of these serotypes and was historically a major cause of invasive disease in children before the introduction of effective vaccines.

Unencapsulated strains: Also known as non-typeable H. influenzae (NTHi), these strains lack a capsule and cannot be serotyped. They are generally less invasive than encapsulated strains but are important causes of mucosal infections and are increasingly recognized as significant pathogens, particularly in adults with chronic respiratory conditions.

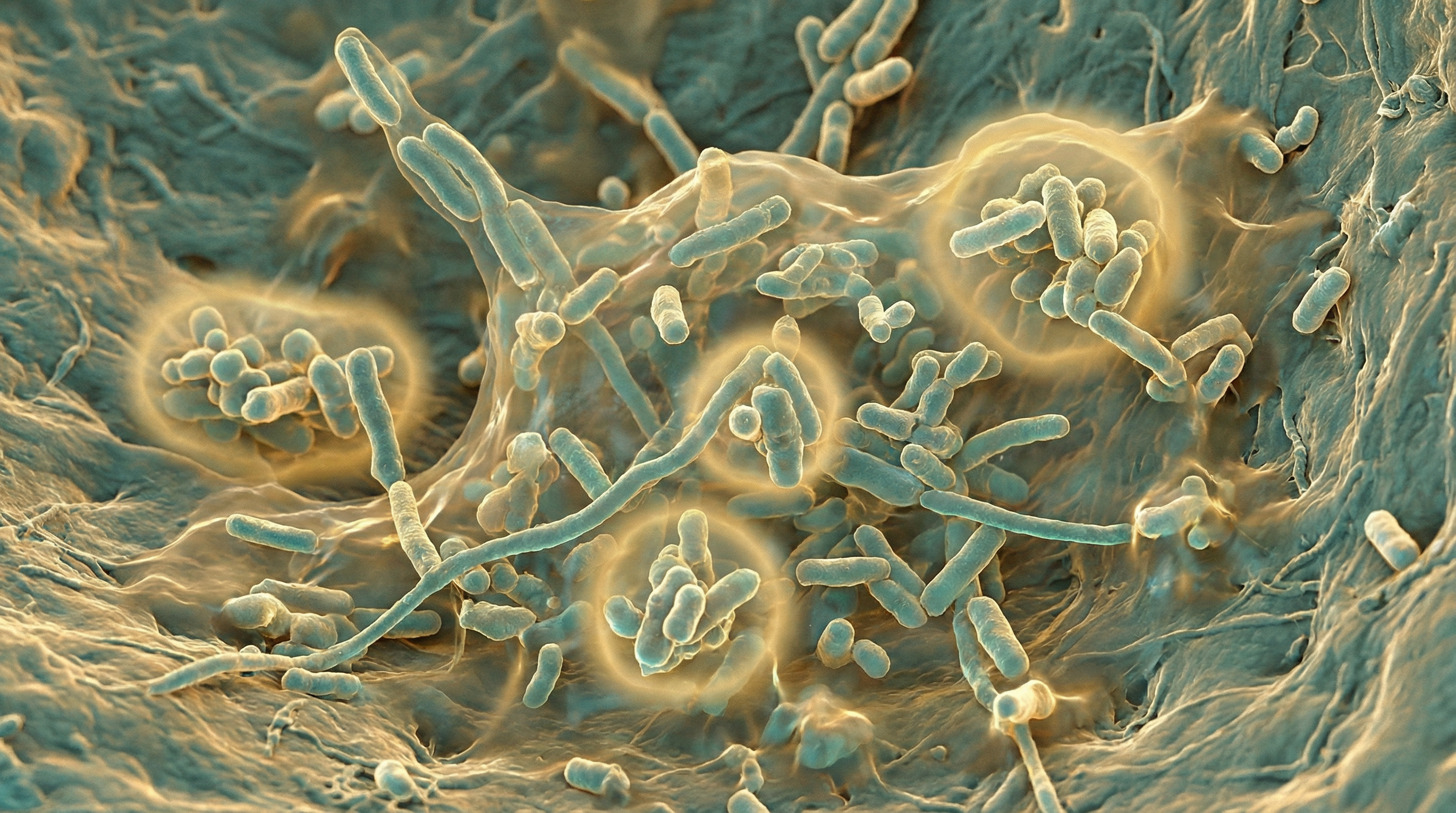

Morphologically, H. influenzae appears as small, pleomorphic rods or coccobacilli, approximately 0.2-0.3 μm by 0.5-2.0 μm in size. When grown on chocolate agar, it forms small, round, convex, colorless-to-gray, opaque colonies with a characteristic "mousy" odor.

The genome of H. influenzae was the first free-living organism to have its complete genome sequenced in 1995, a milestone in genomics. The genome is relatively small, approximately 1.83 million base pairs, encoding about 1,740 proteins. Genomic studies have revealed considerable genetic diversity among strains, with evidence of frequent horizontal gene transfer and phase variation contributing to the bacterium's adaptability.

Role in Human Microbiome

H. influenzae is primarily associated with the human respiratory tract, where it can exist as a commensal organism or act as a pathogen under certain conditions. Its natural habitat includes:

Nasopharynx: H. influenzae commonly colonizes the nasopharynx, particularly in children. Colonization rates vary by age, with up to 80% of children carrying the organism at some point during childhood, while adult carriage rates are generally lower (around 20-40%).

Upper respiratory tract: Beyond the nasopharynx, H. influenzae can be found throughout the upper respiratory tract, including the oropharynx, sinuses, and middle ear.

Lower respiratory tract: While the lower respiratory tract is normally sterile, H. influenzae can colonize the bronchi and lungs in individuals with underlying respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or bronchiectasis.

The relationship between H. influenzae and the host is complex and dynamic:

Commensal relationship: In many individuals, particularly healthy adults, H. influenzae exists as part of the normal respiratory microbiota without causing disease. In this commensal state, it may even contribute to colonization resistance against more pathogenic organisms.

Opportunistic pathogen: Under certain conditions, such as viral co-infection, immune suppression, or disruption of the respiratory epithelium, H. influenzae can transition from a commensal to a pathogen, causing localized or invasive infections.

Persistent colonization: In individuals with chronic respiratory conditions, H. influenzae can establish persistent colonization, contributing to ongoing inflammation and tissue damage. Studies have shown that the same strain can persist in the respiratory tract for months or even years in patients with COPD.

Multiple strain colonization: Research has demonstrated that individuals can be simultaneously colonized with multiple distinct strains of H. influenzae, adding complexity to the host-pathogen relationship and potentially influencing disease progression and treatment outcomes.

The acquisition and carriage of H. influenzae are influenced by various factors:

Age: Colonization is more common in children than adults, with peak carriage rates occurring in early childhood.

Season: Some studies suggest seasonal variation in carriage rates, with higher prevalence during winter months.

Crowding: Close contact environments, such as daycare centers or crowded households, facilitate transmission and increase colonization rates.

Vaccination: The introduction of Hib vaccines has dramatically reduced the carriage of H. influenzae type b, altering the epidemiology of the organism.

Antibiotic use: Prior antibiotic exposure can influence the carriage of H. influenzae, potentially selecting for resistant strains.

Underlying health conditions: Individuals with chronic respiratory diseases or immunodeficiencies often have higher rates of H. influenzae colonization.

Health Implications

H. influenzae is associated with a spectrum of diseases, ranging from mild localized infections to severe invasive disease. The health implications vary depending on the strain (encapsulated vs. non-typeable), host factors, and site of infection.

Invasive Diseases

Invasive H. influenzae disease (IHD) refers to infections where the bacterium invades normally sterile sites such as the bloodstream, cerebrospinal fluid, or joint fluid. Historically, H. influenzae type b (Hib) was the predominant cause of invasive disease, particularly in children under 5 years of age. Since the introduction of effective Hib vaccines in the 1990s, the epidemiology has shifted, with non-type b strains and NTHi now causing a larger proportion of invasive disease, particularly in adults and the elderly.

Key invasive diseases include:

Meningitis: Before widespread vaccination, Hib was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in children. Symptoms include fever, headache, stiff neck, altered mental status, and in infants, bulging fontanelle. Despite appropriate antibiotic treatment, Hib meningitis has a mortality rate of 3-6% and can result in permanent neurological sequelae in 15-30% of survivors.

Epiglottitis: An acute, life-threatening infection of the epiglottis that can rapidly lead to airway obstruction. Classic symptoms include sudden onset of high fever, sore throat, drooling, and respiratory distress. This condition requires immediate medical attention and often airway management.

Septic arthritis: Infection of joint spaces, most commonly affecting the hip, knee, or ankle in children. Symptoms include joint pain, swelling, warmth, and limited range of motion.

Bacteremia/septicemia: Bloodstream infection that can lead to septic shock. This can occur as a primary infection or secondary to another focus of infection.

Cellulitis: Infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, often occurring on the face or neck in children with Hib.

Osteomyelitis: Infection of the bone, which can be acute or chronic and may result in long-term complications if not adequately treated.

Non-invasive Diseases

Non-invasive infections caused by H. influenzae, particularly NTHi, affect the respiratory mucosa and are among the most common bacterial infections worldwide:

Otitis media: NTHi is one of the leading causes of acute otitis media (middle ear infection) in children, along with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Symptoms include ear pain, fever, and irritability. Recurrent otitis media can lead to hearing loss and developmental delays in children.

Sinusitis: Infection of the paranasal sinuses, causing facial pain, nasal congestion, and purulent nasal discharge. NTHi is a common cause of both acute and chronic sinusitis.

Bronchitis: Inflammation of the bronchial tubes, often presenting with cough, sputum production, and wheezing. NTHi is frequently isolated from patients with acute bronchitis.

Pneumonia: Infection of the lung parenchyma, causing fever, cough, sputum production, and respiratory distress. NTHi is an important cause of community-acquired pneumonia, particularly in the elderly and those with underlying lung disease.

Conjunctivitis: Infection of the conjunctiva causing redness, discharge, and discomfort. NTHi is a common cause of purulent conjunctivitis, particularly in children.

Chronic Respiratory Diseases

H. influenzae, particularly NTHi, plays a significant role in chronic respiratory diseases:

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): NTHi is one of the most common bacteria isolated during acute exacerbations of COPD. Persistent colonization with NTHi is associated with increased airway inflammation, more frequent exacerbations, and accelerated decline in lung function.

Bronchiectasis: A condition characterized by permanent dilation of the bronchi. NTHi colonization in bronchiectasis is associated with more severe disease, increased frequency of exacerbations, and poorer quality of life.

Cystic Fibrosis: While not as prevalent as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus, NTHi can colonize the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis and contribute to pulmonary exacerbations.

Chronic Rhinosinusitis: NTHi is frequently isolated from the sinuses of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and may contribute to persistent inflammation and symptoms.

Special Populations

Certain populations are at increased risk for H. influenzae infections:

Children: Despite vaccination, children remain at risk for NTHi infections, particularly otitis media and sinusitis.

Elderly: Older adults have increased susceptibility to NTHi respiratory infections, including pneumonia and exacerbations of chronic lung disease.

Immunocompromised individuals: Those with primary immunodeficiencies, HIV/AIDS, malignancy, or on immunosuppressive therapy are at increased risk for both invasive and non-invasive H. influenzae infections.

Indigenous populations: Some indigenous populations worldwide continue to experience higher rates of invasive H. influenzae disease, even in the post-vaccine era.

Individuals with anatomical or functional asplenia: Those without a functioning spleen are at increased risk for invasive disease due to encapsulated bacteria, including H. influenzae.

Antibiotic Resistance (2024-2025 Data)

Antibiotic resistance in H. influenzae is an escalating global health crisis, with geographic hotspots in Asia and the West Pacific[4]:

Global Surveillance (13,869 isolates, 2013-2022):

- Beta-lactamase production: 24.1% globally

- Ampicillin susceptibility: 71.7% (only 59.5% in Asia-West Pacific)

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate: 94.4% susceptibility

- Fluoroquinolones: 99.2% susceptibility (reserve this for serious infections)

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole: 65.2% (avoid for empirical therapy)

BLNAR (Beta-Lactamase-Negative Ampicillin Resistance) prevalence varies dramatically:

- Vietnam: 87.5% (highest globally)

- Japan: 70.8%

- Korea: 65.7%

- Taiwan: 65.9%

Critical Warning: Reliance on nitrocefin test alone to predict beta-lactam susceptibility leads to false susceptibility results—BLNAR strains are missed by this test, resulting in treatment failures.

China Resistance Trends (21,723 isolates, 2019-2024)[5]:

- Beta-lactamase production: 71.82%

- Ampicillin resistance: 79.05%

- Azithromycin resistance: 49.67% (continuous upward trend)

- Ceftriaxone: 0.62% resistance (remains effective)

- Levofloxacin: 0.11% resistance (reserve agent)

Biofilm Formation and Clinical Significance

Biofilm formation is central to NTHi chronicity, recurrence, and treatment failure[6]:

Key Statistics:

- 82.5% of clinical NTHi isolates from otitis media form biofilms

- 70% of COPD patients are colonized with NTHi

- Biofilms require 1000-fold higher antibiotic concentrations for eradication vs planktonic bacteria

- High biofilm producers: 21.4% treatment failure vs 8.2% in weak-biofilm group

Molecular Mechanisms:

- Key genes: pilA (Type IV pilus) and hifA determine chronicity

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA) stabilizes biofilm matrix

- DNABII proteins (Integration Host Factor) serve as structural scaffold

- Quorum sensing via LuxS/AI-2 and QSeB/C systems

Antibiotic Efficacy in Biofilms:

- Ciprofloxacin: 100% vs planktonic → 68% vs biofilm

- Azithromycin: 100% vs planktonic → 57% vs biofilm

- Amoxicillin: 100% vs planktonic → 4% vs biofilm

Novel Therapeutic Approaches

Biofilm-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies[7]: Monoclonal antibodies against PilA and IHF (Integration Host Factor) in chinchilla otitis media models:

- Disrupt biofilms and induce "newly released" (NRel) bacterial phenotype

- 4-8 fold increase in antibiotic sensitivity relative to planktonic states

- Maintain eubiotic microbiome (minimal feature loss) unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics that cause significant dysbiosis

P5/P26 Multicomponent Vaccine[8]: Analysis of 1,144 NTHi genomes (2017-2022) identified promising vaccine candidates:

- P5: Binds human Factor H to escape complement lysis; vaccination reduces this virulence factor

- P26: 90-100% conserved across NTHi isolates

- Synergistic clearance when combined in animal models

Metabolic Activities

H. influenzae exhibits several key metabolic characteristics that enable it to survive and thrive in the human respiratory tract:

Nutrient Acquisition

Hemin (Factor X) requirement: H. influenzae cannot synthesize protoporphyrin IX, a precursor for heme, and must acquire heme or hemin from the environment. It possesses multiple systems for heme acquisition from host sources, including hemoglobin, hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes, and heme-hemopexin complexes.

NAD (Factor V) requirement: The bacterium lacks the ability to synthesize nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) de novo and must obtain it from the environment. It can utilize NAD, nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), or nicotinamide riboside (NR) as precursors.

Iron acquisition: Beyond heme, H. influenzae has multiple systems for acquiring free iron, including siderophore-independent mechanisms and transferrin-binding proteins.

Amino acid metabolism: The bacterium can utilize various amino acids as carbon and nitrogen sources, with preferences that may vary between strains.

Energy Metabolism

Carbohydrate utilization: H. influenzae can metabolize various sugars, including glucose, fructose, and galactose, primarily through the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (glycolytic) pathway.

Respiration: As a facultative anaerobe, H. influenzae can use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor under aerobic conditions. Under anaerobic conditions, it can use nitrate or other alternative electron acceptors.

Fermentation: In the absence of suitable electron acceptors, H. influenzae can ferment carbohydrates, producing mixed acids including acetate, formate, and succinate.

Adaptation to the Respiratory Environment

Oxidative stress response: H. influenzae possesses mechanisms to detoxify reactive oxygen species encountered in the respiratory tract, including catalase, peroxiredoxin, and superoxide dismutase.

pH adaptation: The bacterium can adapt to the varying pH environments encountered in different parts of the respiratory tract.

Biofilm formation: H. influenzae can form biofilms, structured communities of bacteria embedded in an extracellular matrix, which provides protection from host defenses and antibiotics. Biofilm formation involves complex metabolic adaptations, including changes in gene expression and metabolic pathways.

Quorum sensing: The bacterium uses autoinducer-2 (AI-2) mediated quorum sensing to coordinate gene expression based on population density, influencing biofilm formation and virulence.

Interaction with Host Metabolites

Mucin utilization: H. influenzae can degrade and utilize mucins, the major glycoproteins in respiratory mucus, as a nutrient source.

Sialic acid metabolism: The bacterium can acquire and metabolize sialic acid, a common terminal sugar on host glycoproteins. It can also incorporate sialic acid into its lipooligosaccharide (LOS), mimicking host structures and evading immune recognition.

Nucleotide salvage: H. influenzae can salvage nucleotides and nucleosides from the host environment, which is particularl (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)