Staphylococcus epidermidis

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a gram-positive, coagulase-negative coccus that is one of the most abundant bacterial species colonizing human skin and mucous membranes. As a predominant member of the skin microbiome, S. epidermidis exhibits a dual lifestyle, functioning primarily as a beneficial commensal organism but also capable of acting as an opportunistic pathogen, particularly in healthcare settings and in immunocompromised individuals.

Key Characteristics

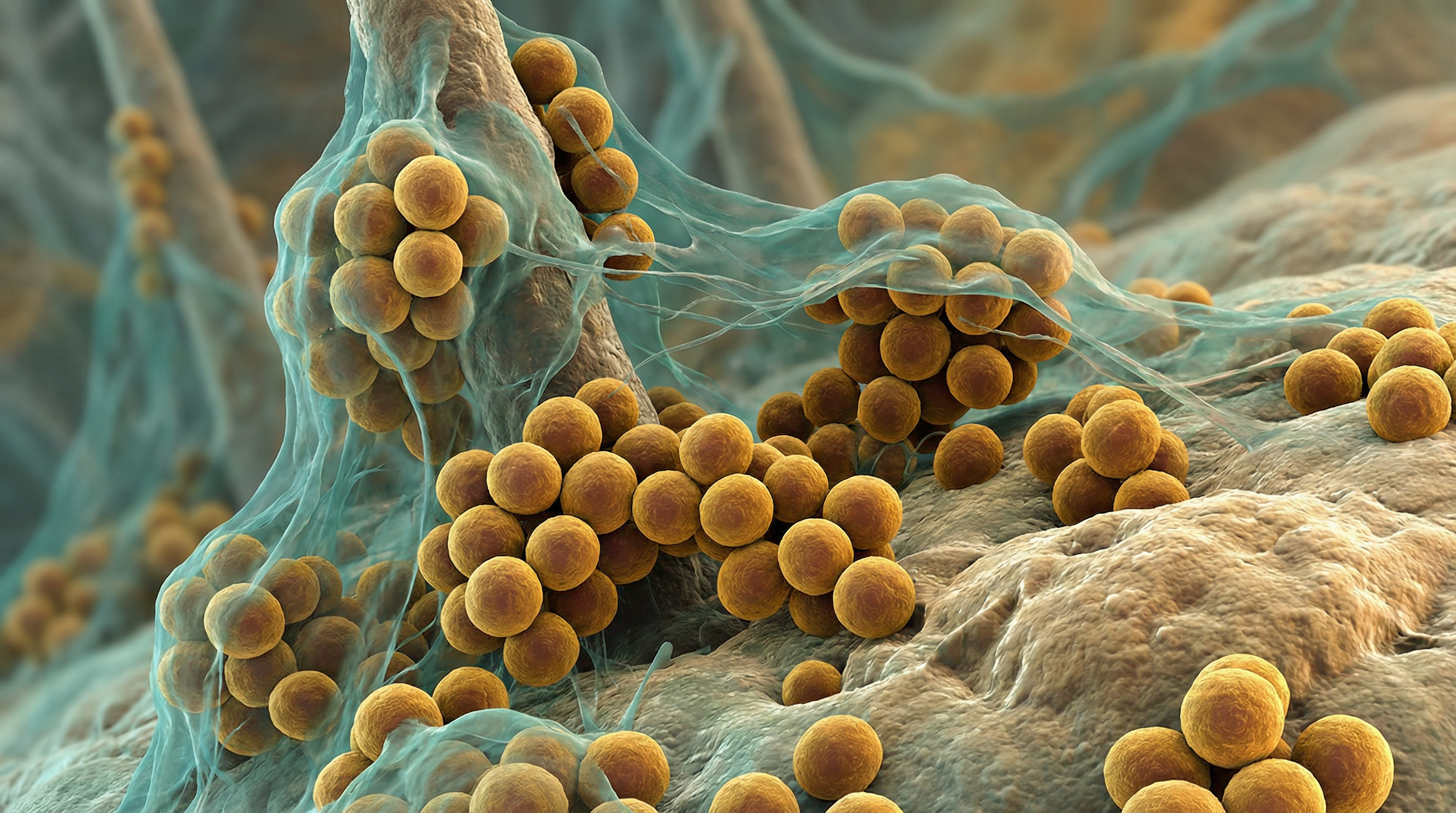

S. epidermidis belongs to the family Staphylococcaceae and appears microscopically as grape-like clusters of cocci. The bacterium is non-motile, non-spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, and catalase-positive. Unlike its relative Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis is coagulase-negative, which is an important diagnostic distinction.

On blood agar, S. epidermidis typically forms small, white, non-hemolytic colonies. The bacterium can grow in environments with high salt concentrations (up to 10% NaCl) and at temperatures ranging from 15°C to 45°C, with optimal growth at 30-37°C.

A distinguishing feature of S. epidermidis is its ability to form robust biofilms on both biotic and abiotic surfaces. This biofilm-forming capacity is mediated by the production of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), encoded by the icaADBC operon, as well as various surface proteins that facilitate attachment and cell-to-cell adhesion.

Genomic analysis has revealed that S. epidermidis has an open pangenome, with approximately 80% core genes and 20% variable genes. This genetic flexibility, facilitated by mobile genetic elements including phages and plasmids, contributes to its adaptability to various niches and lifestyles.

Role in Human Microbiome

S. epidermidis is one of the most abundant bacterial species on human skin, where it primarily colonizes:

- Sebaceous areas (face, scalp, upper chest, back)

- Moist areas (axillae, antecubital fossae, nares)

- Dry areas (forearms, legs)

- Mucous membranes

As an early colonizer of the skin, S. epidermidis is present on the skin of newborns shortly after birth and remains a stable component of the skin microbiome throughout life. Its abundance and distribution vary across different body sites, with higher densities in sebaceous and moist areas.

Within the skin microbiome, S. epidermidis contributes to the ecological balance by:

- Competing with potential pathogens for nutrients and attachment sites

- Producing antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Modulating host immune responses

- Contributing to the acidic pH of the skin surface

- Participating in the development and maintenance of the skin barrier

Recent studies have shown that S. epidermidis strain-level diversity is influenced by both the host and the specific skin site, with evidence of horizontal gene transfer between strains colonizing different skin sites on the same individual.

Health Implications

Beneficial Effects

Recent research (2020-2025) has reframed S. epidermidis as an active commensal controlling inflammation, supporting antimicrobial defenses, and stabilizing the cutaneous barrier:

Antimicrobial Peptide Production

S. epidermidis produces multiple antimicrobials that protect against pathogens:

Lantibiotics:

- Epidermin, Epilancin A37, Pep5 - direct inhibition of pathogenic bacteria including S. aureus

Epifadin (discovered 2023):

- Novel hybrid NRP-polyketide molecule from strain IVK83

- Broad-spectrum antimicrobial with unique "fading strategy" - very short half-life minimizes microbiome damage

- Effectively eliminated nasal S. aureus colonization in cotton rat model

- Proposed as probiotic approach for at-risk patients

Phenol-Soluble Modulins (PSMs):

- PSMδ and delta-toxin synergize with host AMP LL-37 to kill S. aureus and Group A Streptococcus

- Context-dependent: beneficial at low density, inflammatory at high density

Esp Protease: Degrades proteins crucial for S. aureus biofilm formation and host epithelial adhesion

Immune System Modulation

Skin as autonomous lymphoid organ (Nature, 2024):

- Skin generates S. epidermidis-specific antibody responses independently of secondary lymphoid organs

- Langerhans cells capture antigens; Tregs convert to T follicular helper cells

- Tertiary lymphoid structures form in skin

- Specific serum antibodies persist >200 days

- Locally formed IgG2b and IgG2c sufficient to control microbial biomass and prevent systemic infection

Innate immune activation:

- Activates γδ T cells and upregulates Perforin-2 (P-2) in human skin ex vivo

- P-2 upregulation correlates with increased ability to kill intracellular S. aureus

- Activates non-inflammatory skin-resident CD11B+ dendritic cells

- Induces IL-17A+ CD8+ T cell homing to epidermis

Regulatory mechanisms:

- Induces host regulatory protein A20, inhibiting NF-κB to limit inflammation

- Neonatal colonization establishes immune tolerance via Treg activation

- Stimulates MAIT cells to promote tissue repair

Barrier Function

- Produces sphingomyelinase generating ceramides to prevent skin dehydration

- Stimulates filaggrin expression maintaining barrier integrity

- Produces 6-HAP potentially protecting against skin neoplasia

- Stimulates β-defensin-3, β-defensin-4, and cathelicidin (LL-37) production

Pathogenic Potential

Despite its predominantly beneficial role, S. epidermidis can act as an opportunistic pathogen under certain conditions:

Device-Associated Infections

S. epidermidis is the leading cause of chronic biofilm-associated infections:

- Prevalence: Causes ~30% of central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and prosthetic joint infections (PJI)

- Mechanism: Infection represents "accidental pathogenesis" rather than primary survival strategy

- Biofilm role: Most important contributor via Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin (PIA/PNAG) and Accumulation Associated Protein (Aap)

Biofilm-Mediated Immune Evasion (2024 Research)

Extracellular DNA (eDNA) in biofilm matrix is primary driver of immune evasion:

- Shifts macrophages to anti-inflammatory state via TLR9 signaling

- CD163+ anti-inflammatory macrophages increased to 73±4.2% with wild-type infection

- CD36+ pro-inflammatory cells declined to 12.79±2.01%

- eDNA-negative mutants more susceptible to phagocytosis and triggered pro-inflammatory response

- TLR9 inhibition increased bacterial uptake 2.8-fold

Infection Predictors (2025 Clinical Data)

Musculoskeletal infection study findings:

- 73.9% of MSI isolates were strong/moderate biofilm producers

- IS256 transposable element: 8-fold increased risk of persistent infection recurrence (p<0.05)

- Weak biofilms protective: Reduced recurrence chance by 93%

- MSI-derived isolates phenotypically and genetically distinct from commensals

- Rifampicin resistance: I527M mutation in rpoB gene detected only in MSI isolates

Methicillin Resistance (MRSE) Epidemiology

COVID-19 pandemic impact:

- MRSE colonization increased from 0.2% to 3.5% (17.5-fold) during pandemic

- Overall MRS colonization rose from 8.6% to 54.7%

- 41.9% of MRS strains were multidrug-resistant

- Inducible clindamycin resistance increased from 4.4% to 23.5%

Transmission dynamics (2025 study in MSM population):

- 44.12% MRSE colonization rate (225/510 individuals)

- 20.53% of isolates homologous, forming 12 transmission clusters and 40 routes

- ESS (ESAT-6 secretion system) components associated with virulence

- Fitness tradeoff observed: transmissible strains often lack ica biofilm genes

Clinical significance: Anovaginal MRSE carriage during pregnancy is risk factor for neonatal early and late-onset disease

Metabolic Activities

S. epidermidis exhibits various metabolic capabilities that enable it to thrive on the nutrient-limited environment of the skin:

Carbohydrate metabolism: It can utilize various sugars, including glucose, fructose, and mannose, primarily through glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway.

Lipid metabolism: S. epidermidis can metabolize lipids present in sebum, which is abundant in sebaceous areas of the skin.

Amino acid metabolism: It possesses pathways for the synthesis and catabolism of various amino acids.

Adaptation to osmotic stress: The bacterium can accumulate compatible solutes like glycine betaine and proline to withstand the high salt concentrations and desiccation conditions on the skin.

Oxygen adaptation: As a facultative anaerobe, S. epidermidis can grow in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, allowing it to colonize different skin niches with varying oxygen levels.

Biofilm formation: The production of extracellular polymeric substances for biofilm formation is a key metabolic activity that contributes to both commensalism and pathogenicity.

These metabolic adaptations allow S. epidermidis to persist on the skin despite the challenging conditions of this environment, including nutrient limitation, desiccation, and antimicrobial peptides.

Clinical Relevance

Atopic Dermatitis Connection (2023 Research)

Recent studies reveal context-dependent pathogenic behavior in AD:

- PSMδ and ecpA expression elevated on AD lesional skin compared to healthy skin

- Expression levels correlated with disease severity (Local EASI score)

- EcpA protease: Disrupts barrier allowing PSM penetration; high expression negatively correlated with barrier function

- EcpA-producing strains promoted IL-17a, IL-1β, and IL-6 in skin

- Quorum-sensing regulated: pathogenic at high-density overgrowth

- EcpA identified as therapeutic target for AD management

Mathematical Modeling (2025)

Critical growth window concept:

- S. epidermidis maintains commensal role when growth is within 0.1-0.33 h⁻¹ range

- Outside this range, transitions to pathobiont state

- Sustained oscillations observed in immunocompromised conditions

Therapeutic Strategies

Probiotic approaches:

- Epifadin-producing strains proposed for S. aureus decolonization in at-risk patients

- Live biotherapeutics combined with topical corticosteroids enhance AD treatment outcomes

- Bioengineered S. epidermidis under investigation for anti-cancer therapy and topical vaccinations

Prevention strategies:

- Targeted surveillance in high-risk populations (immunocompromised, pregnant, MSM)

- EcpA inhibitors for AD management

- Biofilm disruption strategies for device-associated infections

- Antimicrobial stewardship to combat MRSE emergence

Diagnostic Advances

- IS256 and biofilm production capacity as predictors of infection recurrence

- Strain-level genetic analysis distinguishes commensal from pathogenic isolates

- Recognition that outcomes tied to specific genetic markers, not species presence alone

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

S. epidermidis engages in complex interactions with other members of the skin microbiome:

Competition with S. aureus: S. epidermidis produces antimicrobial peptides and other factors that inhibit colonization by the more pathogenic S. aureus. This competitive relationship is important for maintaining skin health.

Cooperation with Cutibacterium acnes: In sebaceous areas, S. epidermidis and C. acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) coexist and may engage in metabolic cooperation, with C. acnes producing fatty acids that can be utilized by S. epidermidis.

Interactions with Corynebacterium species: S. epidermidis coexists with various Corynebacterium species on the skin, and these interactions contribute to the overall stability of the skin microbiome.

Horizontal gene transfer: S. epidermidis can exchange genetic material with other staphylococcal species, including virulence and antibiotic resistance genes. For example, the methicillin resistance gene mecA can be transferred between S. epidermidis and S. aureus.

Biofilm communities: In biofilms, S. epidermidis can form mixed communities with other bacteria, which can enhance survival and resistance to antimicrobial agents.

These interactions contribute to the ecological balance of the skin microbiome and can influence both health and disease states.

Research Significance

S. epidermidis has become an important focus of research for several reasons:

Dual lifestyle model: As an organism that can be both beneficial and harmful, S. epidermidis provides a model for understanding the factors that determine commensal versus pathogenic behavior.

Biofilm research: Its robust biofilm-forming capacity makes it a valuable model for studying biofilm formation, development, and dispersal.

Antibiotic resistance: S. epidermidis serves as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes that can be transferred to more pathogenic species, making it important for understanding the spread of resistance.

Skin microbiome studies: As a dominant member of the skin microbiome, S. epidermidis is central to understanding the ecology and function of the skin microbial community.

Probiotic potential: Research is exploring the use of commensal S. epidermidis strains as probiotics to prevent colonization by pathogenic bacteria and to treat skin conditions.

Strain-level diversity: Recent studies on strain-level diversity within S. epidermidis populations are providing insights into microbial adaptation and evolution within the human microbiome.

Continued research on S. epidermidis promises to enhance our understanding of host-microbe interactions and may lead to novel approaches for preventing and treating infections while preserving the beneficial aspects of this important commensal.

References

Severn MM, Horswill AR. Staphylococcus epidermidis and its dual lifestyle in skin health and infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(2):97-111.

Byrd AL, Belkaid Y, Segre JA. The human skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(3):143-155.

Otto M. Staphylococcus epidermidis--the 'accidental' pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(8):555-567.

Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(4):244-253.

Schommer NN, Gallo RL. Structure and function of the human skin microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(12):660-668.

Nakatsuji T, Chen TH, Narala S, et al. Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(378):eaah4680.