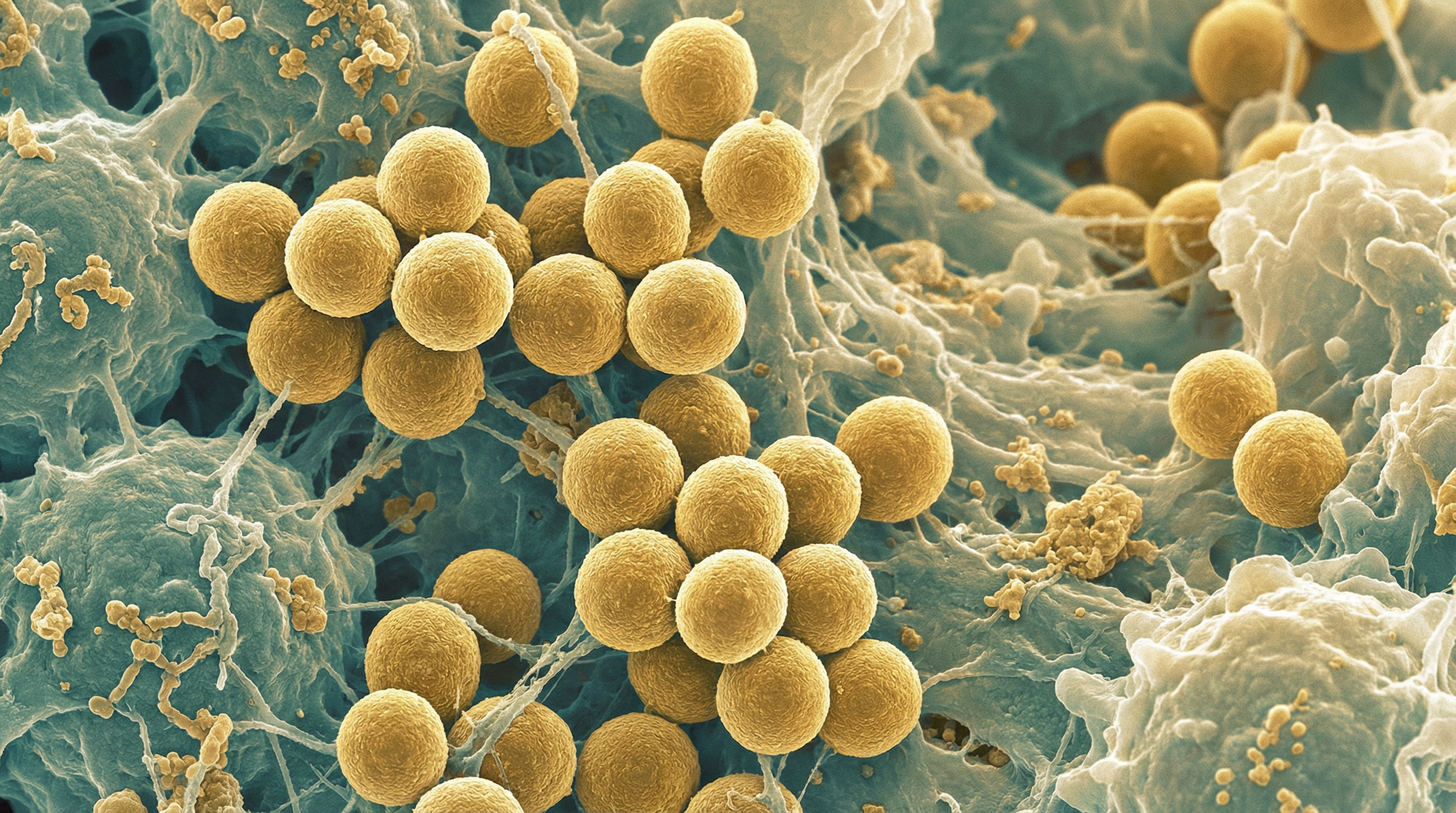

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive, coagulase-positive coccus that is both a commensal organism and a versatile pathogen in humans. While it colonizes approximately 20-30% of the human population asymptomatically and up to 50% are persistent or intermittent carriers, S. aureus is also responsible for a wide range of infections, from relatively minor skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening invasive diseases.[1] Critically, research has demonstrated that life-threatening S. aureus infections emerge from commensal nose bacteria by adaptive evolution, representing a repeatable pathway from colonization to severe disease.[2]

Key Characteristics

S. aureus belongs to the family Staphylococcaceae and appears microscopically as grape-like clusters of cocci. The bacterium is non-motile, non-spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, and catalase-positive. A distinguishing feature of S. aureus is its production of coagulase, an enzyme that causes plasma to clot, which differentiates it from coagulase-negative staphylococci like S. epidermidis.

On blood agar, S. aureus typically forms golden-yellow colonies (hence the name "aureus," meaning "golden" in Latin) with beta-hemolysis. The bacterium can grow in environments with high salt concentrations (up to 15% NaCl) and at temperatures ranging from 15°C to 45°C, with optimal growth at 30-37°C.

S. aureus possesses a remarkable array of virulence factors, including:

- Surface proteins (adhesins) that mediate attachment to host tissues

- Invasins that promote bacterial spread in tissues

- Surface factors that inhibit phagocytosis

- Biochemical properties that enhance survival in phagocytes

- Immunological disguises (protein A)

- Membrane-damaging toxins (hemolysins, leukocidins)

- Exotoxins that damage host tissues or trigger symptoms of disease

- Superantigens that cause toxic shock syndrome and food poisoning

The genome of S. aureus is highly plastic, with approximately 75% core genes and 25% accessory genes. This genetic flexibility, facilitated by mobile genetic elements including phages, plasmids, and pathogenicity islands, contributes to its adaptability to various niches and its ability to acquire antibiotic resistance.

Role in Human Microbiome

S. aureus colonizes several niches in the human body, primarily:

- Anterior nares (primary reservoir, 20-30% of population)

- Skin, particularly in moist areas

- Throat

- Perineum

- Gastrointestinal tract

Nasal carriage of S. aureus is classified as:

- Persistent (approximately 20% of population)

- Intermittent (approximately 30% of population)

- Non-carriers (approximately 50% of population)

Persistent carriers typically harbor higher loads of S. aureus and have an increased risk of developing infections. Nasal colonization is a significant risk factor for subsequent infection in other body sites, as individuals often become infected with their own colonizing strain.

Within the skin microbiome, S. aureus is typically present in low abundance in healthy individuals, where its growth is kept in check by commensal bacteria like S. epidermidis and host defense mechanisms. However, in certain skin conditions like atopic dermatitis, S. aureus can become overabundant, contributing to dysbiosis and exacerbation of inflammation.

Health Implications

Pathogenic Potential

S. aureus is responsible for a wide spectrum of infections:

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs): The most common manifestations include:

- Impetigo: Superficial skin infection characterized by honey-colored crusts

- Folliculitis: Infection of hair follicles

- Furuncles and carbuncles: Deeper infections of hair follicles

- Cellulitis: Infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue

- Abscesses: Localized collections of pus

- Surgical site infections

Invasive infections:

- Bacteremia and sepsis

- Endocarditis

- Pneumonia

- Osteomyelitis

- Septic arthritis

- Device-related infections

Toxin-mediated diseases:

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Food poisoning

Role in inflammatory skin conditions:

- Atopic dermatitis: S. aureus colonizes over 90% of atopic dermatitis lesions and contributes to disease severity through various mechanisms

- Chronic wounds: S. aureus is frequently isolated from non-healing wounds, where it forms biofilms and impairs healing

The pathogenicity of S. aureus is multifactorial, involving:

- Adherence to host tissues

- Invasion and tissue destruction

- Evasion of host immune responses

- Biofilm formation

- Production of toxins and enzymes

Antibiotic Resistance

A major concern with S. aureus is its ability to develop resistance to multiple antibiotics:

- Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) emerged in the 1960s and has become endemic in many healthcare settings worldwide

- Community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) emerged in the 1990s, causing infections in otherwise healthy individuals without healthcare exposure

- Vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VISA/VRSA) represent a concerning development in antibiotic resistance

- Multidrug-resistant strains that are resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics pose significant therapeutic challenges

The emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus strains have significant implications for public health and healthcare costs.

Metabolic Activities

S. aureus exhibits versatile metabolic capabilities that enable it to adapt to various host environments:

Carbohydrate metabolism: It can utilize various sugars, including glucose, fructose, and mannose, primarily through glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway.

Adaptation to oxygen limitation: As a facultative anaerobe, S. aureus can switch between aerobic respiration, nitrate respiration, and fermentation depending on oxygen availability.

Adaptation to nutrient limitation: It can scavenge essential nutrients like iron from the host through siderophores and other acquisition systems.

pH adaptation: S. aureus can survive in a wide range of pH conditions, from the acidic environment of the skin (pH ~5.5) to the more neutral pH of the bloodstream.

Osmotic stress response: It can accumulate compatible solutes like glycine betaine, proline, and taurine to withstand high salt concentrations and desiccation conditions on the skin.

Biofilm formation: The production of extracellular polymeric substances for biofilm formation is a key metabolic activity that enhances survival in hostile environments and resistance to antimicrobials.

These metabolic adaptations allow S. aureus to persist in diverse host niches and contribute to its success as both a commensal and a pathogen.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical significance of S. aureus is substantial:

Burden of disease: S. aureus is one of the leading causes of healthcare-associated infections worldwide and a major cause of community-acquired infections.

Antibiotic resistance: The emergence and spread of MRSA and other resistant strains have complicated treatment and increased healthcare costs.

Recurrent infections: S. aureus SSTIs frequently recur, with recurrence rates of 30-50% within a year after the initial infection.

Persistent colonization: Eradication of S. aureus carriage is challenging, particularly in individuals with certain risk factors or skin conditions.

Diagnostic considerations: Rapid identification of S. aureus and determination of antibiotic susceptibility are crucial for appropriate management.

Treatment approaches:

- Incision and drainage is the primary treatment for purulent SSTIs

- Antibiotic selection depends on local resistance patterns and severity of infection

- Decolonization strategies may be considered for patients with recurrent infections

- Novel approaches targeting virulence factors or biofilms are under investigation

Prevention strategies:

- Hand hygiene and infection control measures in healthcare settings

- Screening and decolonization in high-risk populations

- Vaccination strategies (currently under development)

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

S. aureus engages in complex interactions with other members of the human microbiome:

Competition with S. epidermidis: S. epidermidis produces antimicrobial peptides and other factors that inhibit S. aureus colonization. Conversely, S. aureus can outcompete S. epidermidis under certain conditions through its own arsenal of competitive mechanisms.

Interactions with Corynebacterium species: Some Corynebacterium species can inhibit S. aureus growth, while others may facilitate its colonization.

Relationship with Cutibacterium acnes: In sebaceous areas, S. aureus and C. acnes may compete for resources, with C. acnes producing fatty acids that can inhibit S. aureus growth.

Horizontal gene transfer: S. aureus can exchange genetic material with other staphylococcal species, including virulence and antibiotic resistance genes.

Polymicrobial infections: In settings like chronic wounds or cystic fibrosis, S. aureus often participates in polymicrobial communities where interspecies interactions can enhance virulence and antibiotic resistance.

Microbiome dysbiosis: Overgrowth of S. aureus is associated with dysbiosis in various contexts, including atopic dermatitis, where it correlates with reduced microbial diversity.

These interactions have important implications for colonization, infection, and the development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting the microbiome.

Research Significance

S. aureus remains a major focus of research for several reasons:

Antibiotic resistance: Understanding the mechanisms and epidemiology of resistance is crucial for developing strategies to combat resistant strains.

Virulence mechanisms: Elucidating the complex interplay of virulence factors and their regulation provides insights into pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets.

Host-pathogen interactions: Understanding how S. aureus interacts with the host immune system informs vaccine development and immunomodulatory approaches.

Biofilm formation: Research on biofilm development and dispersal may lead to novel approaches for treating biofilm-associated infections.

Microbiome interactions: Studying the relationship between S. aureus and other microbiome members may reveal probiotic or ecological approaches to preventing colonization and infection.

Adaptation to the skin environment: Understanding how S. aureus adapts to the challenging conditions of the skin may reveal vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically.

Novel therapeutics: Development of alternatives to conventional antibiotics, including anti-virulence compounds, phage therapy, and immunotherapeutics, is an active area of research.

Continued research on S. aureus is essential for addressing the significant clinical challenges posed by this versatile pathogen and for developing innovative approaches to prevention and treatment.

References

Gehrke AKE, Giai C, Gómez MI. Staphylococcus aureus Adaptation to the Skin in Health and Persistent/Recurrent Infections. Antibiotics. 2023;12(10):1520.

Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603-661.

Nakatsuji T, Chen TH, Narala S, et al. Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(378):eaah4680.

Paller AS, Kong HH, Seed P, et al. The microbiome in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):26-35.

Liu H, Archer NK, Dillen CA, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Epicutaneous Exposure Drives Skin Inflammation via IL-36-Mediated T Cell Responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22(5):653-666.e5.

Kobayashi T, Glatz M, Horiuchi K, et al. Dysbiosis and Staphylococcus aureus Colonization Drives Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunity. 2015;42(4):756-766.