Herpesviridae in the Human Virome

Overview

Herpesviridae is a family of large, enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses that are ubiquitous in the human population. Eight distinct human herpesviruses have been identified, which are classified into three subfamilies based on their biological properties and genomic characteristics: Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae, and Gammaherpesvirinae. These viruses are remarkable for their ability to establish lifelong latent infections in specific host cells, periodically reactivate to produce infectious virions, and evade host immune responses.

Human herpesviruses are highly prevalent, with seroprevalence rates exceeding 90% for some viruses in adult populations worldwide. Primary infection typically occurs during childhood or adolescence and is often asymptomatic or causes mild, self-limiting disease. Following primary infection, herpesviruses establish latency in specific cell types, where they persist for the lifetime of the host. Periodic reactivation from latency allows for viral transmission to new hosts and maintenance of the viral reservoir within the population.

The eight human herpesviruses include:

Alphaherpesvirinae:

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)

- Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV)

Betaherpesvirinae:

- Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)

- Human herpesvirus 6A and 6B (HHV-6A and HHV-6B)

- Human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7)

Gammaherpesvirinae:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV-8)

Each of these viruses has evolved unique strategies for persistence in the human host, contributing to their remarkable success as human pathogens and integral components of the human virome.

Characteristics

Herpesviruses share several distinctive structural and genomic characteristics:

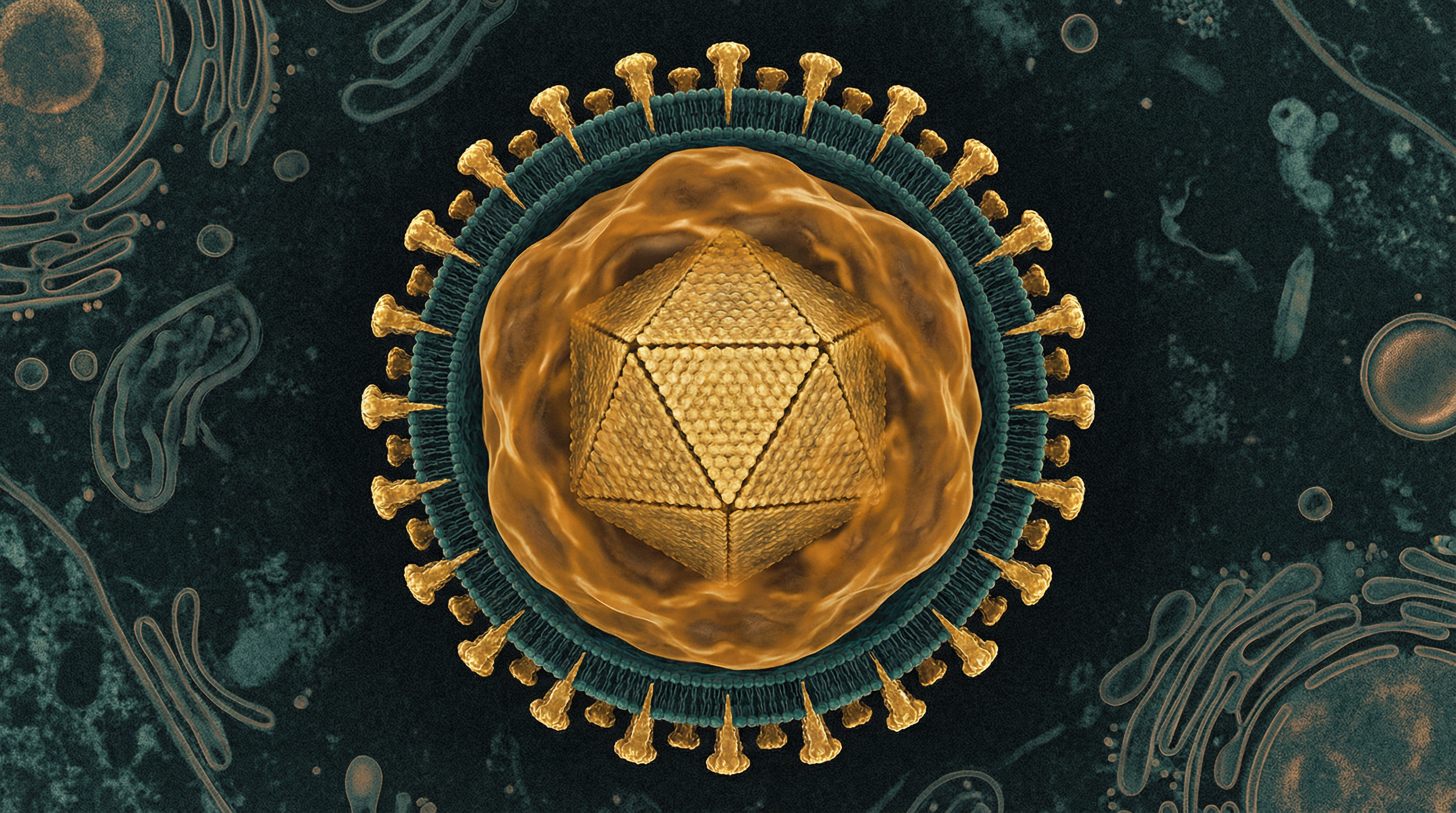

Virion Structure: Mature herpesvirus virions are spherical, enveloped particles with a diameter of approximately 200 nm. The virion consists of:

- A core containing the viral DNA genome

- An icosahedral capsid composed of 162 capsomeres (150 hexons and 12 pentons)

- A tegument layer consisting of viral proteins between the capsid and envelope

- A lipid envelope derived from host cell membranes, containing viral glycoproteins

Genome: Herpesvirus genomes are large, linear, double-stranded DNA molecules ranging from 120 to 235 kilobase pairs (kbp). The genomes contain:

- Terminal and internal repeat sequences

- Unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions

- 70-200 open reading frames (ORFs) encoding viral proteins

- During latency, the genome circularizes to form an episome in the nucleus

Replication Cycle: Herpesviruses undergo a complex replication cycle that includes:

- Attachment and entry via interaction of viral glycoproteins with host cell receptors

- Transport of the nucleocapsid to the nuclear pore

- Release of viral DNA into the nucleus

- Temporal cascade of gene expression (immediate-early, early, and late genes)

- DNA replication via a rolling-circle mechanism

- Assembly of new capsids in the nucleus

- Nuclear egress, tegumentation, and envelopment

- Release of mature virions by exocytosis or cell lysis

Latency: A hallmark of herpesviruses is their ability to establish latency, a state characterized by:

- Maintenance of the viral genome as a circular episome in the nucleus

- Limited viral gene expression

- No production of infectious virions

- Evasion of host immune surveillance

- Capacity for reactivation under specific stimuli

Subfamily-Specific Characteristics:

- Alphaherpesvirinae: Rapid replication cycle, efficient cell destruction, and establishment of latency primarily in sensory neurons

- Betaherpesvirinae: Slow replication cycle, restricted host range, and establishment of latency in monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes

- Gammaherpesvirinae: Tropism for lymphoid cells, establishment of latency in B lymphocytes, and association with lymphoproliferative disorders

Role in Human Microbiome

Herpesviruses are integral components of the human virome, the collection of viruses that inhabit the human body. Their role in the human microbiome is characterized by several key aspects:

Ubiquity and Persistence

Herpesviruses are among the most prevalent viruses in the human population, with seroprevalence rates often exceeding 90% for viruses like HSV-1, VZV, and EBV in adults worldwide. Following primary infection, these viruses establish lifelong latency in specific host cells, becoming permanent residents of the human microbiome. This persistence allows herpesviruses to be transmitted horizontally throughout human populations and vertically across generations.

Tissue Distribution

Different herpesviruses establish latency in specific cell types, contributing to the virome of distinct anatomical sites:

Neuronal Virome: Alphaherpesviruses (HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV) establish latency in sensory neurons of the trigeminal, sacral, and dorsal root ganglia, contributing to the neuronal virome.

Blood and Lymphoid Virome: Betaherpesviruses (HCMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7) establish latency in mononuclear cells, while gammaherpesviruses (EBV and KSHV) establish latency primarily in B lymphocytes, contributing to the blood and lymphoid virome.

Mucosal Virome: During both primary infection and reactivation, herpesviruses replicate in epithelial cells of the oral, respiratory, and genital mucosa, contributing to the mucosal virome.

Viral Shedding and Transmission

Periodic reactivation of latent herpesviruses leads to viral shedding in saliva, genital secretions, or skin lesions, often in the absence of clinical symptoms. This asymptomatic shedding is crucial for viral transmission to new hosts and maintenance of the viral reservoir in the human population. For example, HSV-1, EBV, HCMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7 are frequently shed in saliva, while HSV-2 is commonly shed in genital secretions.

Interaction with Other Microbiome Components

Herpesviruses interact with other components of the human microbiome, including bacteria, fungi, and other viruses. These interactions can be:

Synergistic: Herpesvirus infection may enhance bacterial colonization or pathogenicity, as observed with HSV and bacterial co-infections in genital herpes.

Antagonistic: Some herpesviruses may inhibit the replication of other viruses through mechanisms such as interferon induction or competition for cellular resources.

Modulatory: Herpesviruses can modulate the host immune response, potentially altering the composition and dynamics of the broader microbiome.

Health Implications

The health implications of herpesviruses in the human virome range from asymptomatic infection to severe disease, depending on the specific virus, host factors, and circumstances of infection or reactivation:

Alphaherpesvirinae

Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1):

- Primary infection: Gingivostomatitis, pharyngitis, or asymptomatic infection

- Recurrent infection: Herpes labialis (cold sores), herpes keratitis

- Severe manifestations: Herpes encephalitis, neonatal herpes (when transmitted to newborns)

Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 (HSV-2):

- Primary infection: Genital herpes, aseptic meningitis, or asymptomatic infection

- Recurrent infection: Genital herpes with painful vesicular lesions

- Severe manifestations: Neonatal herpes, increased risk of HIV acquisition

Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV):

- Primary infection: Varicella (chickenpox)

- Reactivation: Herpes zoster (shingles), post-herpetic neuralgia

- Severe manifestations: Pneumonia, encephalitis, vasculopathy

Betaherpesvirinae

Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV):

- Primary infection: Usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent hosts; mononucleosis-like syndrome in some adults

- Reactivation: Generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent hosts

- Severe manifestations: Congenital CMV infection (leading cause of congenital hearing loss and neurodevelopmental disabilities), end-organ disease in immunocompromised hosts (pneumonitis, colitis, retinitis)

Human Herpesvirus 6A and 6B (HHV-6A and HHV-6B):

- Primary infection: Exanthem subitum (roseola infantum) caused by HHV-6B

- Reactivation: Usually asymptomatic

- Severe manifestations: Encephalitis, graft rejection, and delayed engraftment in transplant recipients

Human Herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7):

- Primary infection: May cause exanthem subitum or asymptomatic infection

- Reactivation: Usually asymptomatic

- Severe manifestations: Rare, but may contribute to complications in immunocompromised hosts

Gammaherpesvirinae

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV):

- Primary infection: Infectious mononucleosis in adolescents and adults; usually asymptomatic in children

- Chronic infection: Generally asymptomatic

- Severe manifestations: Associated with multiple malignancies (Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma), post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome

Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV-8):

- Primary infection: Usually asymptomatic

- Chronic infection: Generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent hosts

- Severe manifestations: Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, multicentric Castleman disease (particularly in immunocompromised hosts)

Immune Modulation

Beyond their direct pathogenic effects, herpesviruses significantly modulate host immune responses, with potential implications for overall health:

Immune Evasion: Herpesviruses encode numerous proteins that interfere with innate and adaptive immune responses, potentially compromising host defense against other pathogens.

Immune Stimulation: Chronic herpesvirus infection may contribute to persistent immune activation and inflammation, potentially contributing to age-related diseases and immunosenescence.

Autoimmunity: Molecular mimicry between herpesvirus and host antigens may contribute to autoimmune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis (associated with EBV) and type 1 diabetes.

Metabolic Activities

The metabolic activities of herpesviruses within the human host vary depending on their replication state (lytic or latent) and the specific virus:

Lytic Replication

During lytic replication, herpesviruses dramatically alter host cell metabolism to support viral replication:

Nucleotide Metabolism: Herpesviruses encode enzymes involved in nucleotide metabolism, including thymidine kinase, ribonucleotide reductase, and dUTPase, which increase the pool of nucleotides available for viral DNA synthesis.

Energy Metabolism: Lytic herpesvirus infection increases glycolysis and glutaminolysis to provide energy and carbon sources for viral replication. For example, HCMV infection induces a Warburg-like metabolic shift, increasing glucose uptake and lactate production.

Lipid Metabolism: Herpesviruses modulate host lipid metabolism to support the formation of viral envelopes and the creation of specialized membrane compartments for viral assembly. HCMV, for instance, increases fatty acid synthesis and alters the composition of cellular membranes.

Protein Synthesis: Herpesviruses redirect the host translational machinery to prioritize viral protein synthesis. They employ various mechanisms to inhibit host protein synthesis while selectively promoting the translation of viral mRNAs.

Latent Infection

During latency, herpesvirus metabolic activity is minimal but strategically important:

Episome Maintenance: Latent herpesviruses express proteins necessary for maintaining the viral episome in dividing cells. For example, EBV expresses EBNA1, which tethers the viral genome to host chromosomes during cell division.

MicroRNA Production: Many herpesviruses express microRNAs during latency that regulate both viral and host gene expression. These miRNAs can modulate host cell metabolism, apoptosis, and immune responses without producing immunogenic viral proteins.

Latency-Associated Transcripts: Alphaherpesviruses produce latency-associated transcripts (LATs) that regulate viral gene expression and protect infected neurons from apoptosis, ensuring the survival of the viral reservoir.

Energy Conservation: During latency, herpesviruses minimize their metabolic footprint, conserving energy and resources while avoiding detection by the immune system.

Virus-Specific Metabolic Activities

Different herpesviruses have evolved unique metabolic strategies:

HSV: Encodes enzymes like thymidine kinase and ribonucleotide reductase that are crucial for viral DNA replication in non-dividing neurons.

HCMV: Extensively reprograms host cell metabolism, increasing glucose uptake, glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and fatty acid synthesis to support the production of its large virions.

EBV: Expresses latent membrane proteins (LMPs) that activate signaling pathways like NF-κB and PI3K/Akt, altering cellular metabolism to promote B cell survival and proliferation.

KSHV: Encodes viral proteins that induce the Warburg effect, promoting aerobic glycolysis and angiogenesis, which contribute to Kaposi's sarcoma development.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical relevance of herpesviruses extends beyond their direct pathogenic effects to include their utility as diagnostic markers, therapeutic targets, and models for understanding viral persistence:

Diagnostic Applications

Serological Testing: Detection of herpesvirus-specific antibodies is used to determine past exposure and immunity status. For example, VZV serology may guide vaccination recommendations, while EBV serology aids in diagnosing infectious mononucleosis.

Viral Load Monitoring: Quantitative PCR measurement of herpesvirus DNA in blood or other specimens is crucial for monitoring viral reactivation in immunocompromised patients, particularly transplant recipients at risk for HCMV, EBV, or HHV-6 disease.

Biomarkers of Immune Status: The viral load of certain herpesviruses, particularly HCMV, can serve as a biomarker of immune function. Rising viral loads may indicate excessive immunosuppression in transplant recipients or immune reconstitution in HIV-infected individuals starting antiretroviral therapy.

Therapeutic Considerations

Antiviral Drugs: Several antiviral drugs target herpesvirus replication, including:

- Acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir for HSV and VZV infections

- Ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir for HCMV infections

- These drugs inhibit viral DNA polymerase but do not eliminate latent virus

Vaccines: The VZV vaccine has dramatically reduced the incidence of chickenpox and shingles. Efforts to develop vaccines against other herpesviruses, particularly HSV and HCMV, are ongoing.

Novel Therapeutic Approaches: Emerging strategies aim to target latent infection or prevent reactivation:

- Epigenetic modifiers to maintain viral latency

- CRISPR/Cas9-based approaches to cleave or modify latent viral genomes

- Immunotherapeutic approaches, including therapeutic vaccines and adoptive T cell therapy

Disease Associations and Complications

Neurological Disorders: Herpesviruses are associated with various neurological conditions:

- HSV encephalitis, a rare but severe form of brain inflammation

- VZV vasculopathy and post-herpetic neuralgia

- Potential associations between HHV-6 and multiple sclerosis

- Possible role of EBV in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis

Oncogenesis: Several herpesviruses have oncogenic potential:

- EBV is associated with Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and gastric carcinoma

- KSHV causes Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease

- The oncogenic mechanisms include expression of viral oncoproteins, induction of chronic inflammation, and modulation of cellular signaling pathways

Transplantation Complications: Herpesviruses are major pathogens in transplant recipients:

- HCMV can cause end-organ disease and is associated with graft rejection

- EBV can cause post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder

- HHV-6 is associated with encephalitis and delayed engraftment

Congenital Infections: HCMV is the leading infectious cause of congenital birth defects, affecting approximately 0.5-1% of all newborns worldwide and causing sensorineural hearing loss, vision impairment, and neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Herpesviruses interact with other components of the human microbiome, including bacteria, fungi, and other viruses, influencing the overall microbial ecology and potentially affecting health outcomes:

Interactions with Bacteria

Synergistic Pathogenesis: Herpesvirus infections can enhance bacterial colonization and pathogenicity:

- HSV infection of epithelial surfaces disrupts mucosal barriers, potentially facilitating bacterial invasion

- HCMV infection of monocytes and macrophages impairs phagocytosis and bacterial killing

- EBV-induced immunosuppression may contribute to bacterial superinfections

Bacterial Triggering of Viral Reactivation: Bacterial infections and their associated inflammatory responses can trigger herpesvirus reactivation:

- Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can induce HSV reactivation through toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling

- Periodontal bacteria have been associated with increased EBV and HCMV detection in periodontal lesions

Microbiome Modulation: Herpesviruses may alter the composition of the bacterial microbiome:

- HCMV infection has been associated with changes in gut microbiota composition in transplant recipients

- HSV shedding correlates with alterations in the vaginal microbiome

Interactions with Other Viruses

Co-infection Dynamics: Herpesviruses frequently co-infect with other viruses, with various outcomes:

- HSV-2 infection increases susceptibility to HIV acquisition and enhances HIV shedding

- HCMV co-infection accelerates HIV disease progression

- EBV and KSHV co-infection enhances the development of primary effusion lymphoma

Viral Interference: Some herpesvirus interactions may be antagonistic:

- Prior HSV-1 infection may provide partial protection against HSV-2 acquisition

- HCMV infection induces interferon responses that can inhibit other viral infections

Transactivation: Some herpesviruses can activate the replication of other viruses:

- HSV infection can activate HIV replication through various mechanisms

- HCMV immediate-early proteins can transactivate the HIV long terminal repeat (LTR)

Interactions with Fungi

Opportunistic Fungal Infections: Herpesvirus-induced immunosuppression may predispose to fungal infections:

- HCMV infection is associated with increased risk of invasive fungal infections in transplant recipients

- EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder treatment often leads to fungal superinfections

Fungal Triggering of Viral Reactivation: Fungal infections and associated inflammatory responses may trigger herpesvirus reactivation, though this area is less well-studied than bacterial triggers.

Novel Triggers of Reactivation

Recent research has identified previously unrecognized environmental factors that can trigger herpesvirus reactivation:

Helminth Co-infection: Helminth infections can reactivate latent gammaherpesviruses through IL-4/Stat6-dependent mechanisms, potentially influencing disease outcomes in co-endemic regions.

Nanoparticle Exposure: Exposure to certain nanoparticles, including carbon black and carbon nanotubes, can trigger reactivation of latent gammaherpesviruses. This finding has potential implications for human health in environments with increasing nanoparticle exposure.

Environmental Pollutants: Various environmental pollutants may trigger herpesvirus reactivation, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of chronic diseases associated with both pollution exposure and viral reactivation.

Research Significance

Herpesviruses continue to be subjects of intense research interest due to their ubiquity, complex biology, and significant impact on human health:

Model Systems for Viral Persistence

Mechanisms of Latency: Herpesviruses provide valuable models for studying viral persistence mechanisms, including:

- Epigenetic regulation of viral gene expression

- Viral strategies for immune evasion

- Mechanisms of viral genome maintenance in dividing and non-dividing cells

Viral Reactivation: Understanding the molecular triggers and pathways of herpesvirus reactivation offers insights into the dynamic relationship between viruses and their hosts, with potential applications for other persistent viral infections.

Therapeutic Development

Antiviral Strategies: Research on herpesvirus biology has led to the development of numerous antiviral drugs, with ongoing efforts to develop:

- Novel polymerase inhibitors with improved efficacy and safety profiles

- Compounds targeting viral proteins essential for latency or reactivation

- Immunotherapeutic approaches to enhance virus-specific immune responses

Vaccine Development: Despite decades of research, effective vaccines are available only for VZV. Ongoing research aims to develop vaccines against other herpesviruses, particularly HSV and HCMV, with potential global health impact.

Gene Therapy Vectors: Modified herpesviruses, particularly HSV, are being developed as vectors for gene therapy due to their large genome capacity, neurotropism, and ability to establish latency.

Disease Associations

Oncogenesis: Research on oncogenic herpesviruses (EBV and KSHV) continues to provide insights into viral oncogenesis mechanisms, including:

- Viral manipulation of cellular signaling pathways

- Modulation of the tumor microenvironment

- Evasion of anti-tumor immune responses

Neurological Disorders: Emerging evidence suggests potential roles for herpesviruses in various neurological conditions, including:

- Multiple sclerosis (associated with EBV)

- Alzheimer's disease (controversial associations with HSV)

- Epilepsy (associated with HHV-6)

Chronic Inflammation: Persistent herpesvirus infection and periodic reactivation may contribute to chronic inflammation, potentially influencing the pathogenesis of various inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

Technological Advances

Single-Cell Analysis: Application of single-cell technologies to herpesvirus research is revealing previously unappreciated heterogeneity in viral gene expression and host responses during both lytic infection and latency.

CRISPR/Cas9 Technology: Genome editing approaches are being applied to:

- Precisely modify herpesvirus genomes for functional studies

- Develop potential therapeutic strategies targeting latent viral genomes

- Engineer improved viral vectors for gene therapy applications

Systems Biology Approaches: Integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is providing comprehensive views of virus-host interactions during different stages of herpesvirus infection.

In conclusion, herpesviruses represent a fascinating and clinically significant component of the human virome. Their ability to establish lifelong latency, periodically reactivate, and modulate host immune responses makes them uniquely successful pathogens and integral members of the human microbiome. Ongoing research continues to uncover the complex biology of these viruses and their multifaceted interactions with the human host, with implications for understanding viral persistence, developing novel therapeutic strategies, and elucidating the pathogenesis of various human diseases.