Polyomaviridae in the Human Virome

Overview

Polyomaviridae is a family of small, non-enveloped viruses with circular double-stranded DNA genomes that establish persistent infections in a wide range of vertebrate hosts. Human polyomaviruses (HPyVs) represent an important component of the human virome, with at least 13 distinct species identified to date. The most well-characterized human polyomaviruses include BK polyomavirus (BKPyV), JC polyomavirus (JCPyV), and Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV).

These viruses are ubiquitous in human populations, with seroprevalence rates of 50-80% for BKPyV and JCPyV, indicating that primary infection typically occurs during childhood. Following primary infection, which is usually asymptomatic, polyomaviruses establish lifelong latent infections, primarily in the urinary tract (BKPyV), central nervous system (JCPyV), or skin (MCPyV).

In immunocompetent individuals, polyomavirus infections remain largely asymptomatic due to effective immune control. However, under conditions of immunosuppression, such as in organ transplant recipients, HIV/AIDS patients, or individuals receiving immunosuppressive therapies, viral reactivation can occur, potentially leading to serious disease. BKPyV reactivation can cause polyomavirus-associated nephropathy (PVAN) in kidney transplant recipients, JCPyV reactivation can lead to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, and MCPyV has been established as the causative agent of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), a rare but aggressive skin cancer.

The discovery of MCPyV in 2008 marked a significant milestone as the first human polyomavirus directly linked to cancer, joining the select group of known human oncogenic viruses. Unlike other human tumor viruses, MCPyV appears to be a common component of the healthy human skin virome, with pathogenic potential emerging only under specific circumstances involving viral genome integration, mutation, and host immunosuppression.

Understanding the complex relationships between human polyomaviruses and their hosts, including their roles as both commensal members of the human virome and potential pathogens, continues to be an active area of research with important implications for human health.

Characteristics

Virion Structure

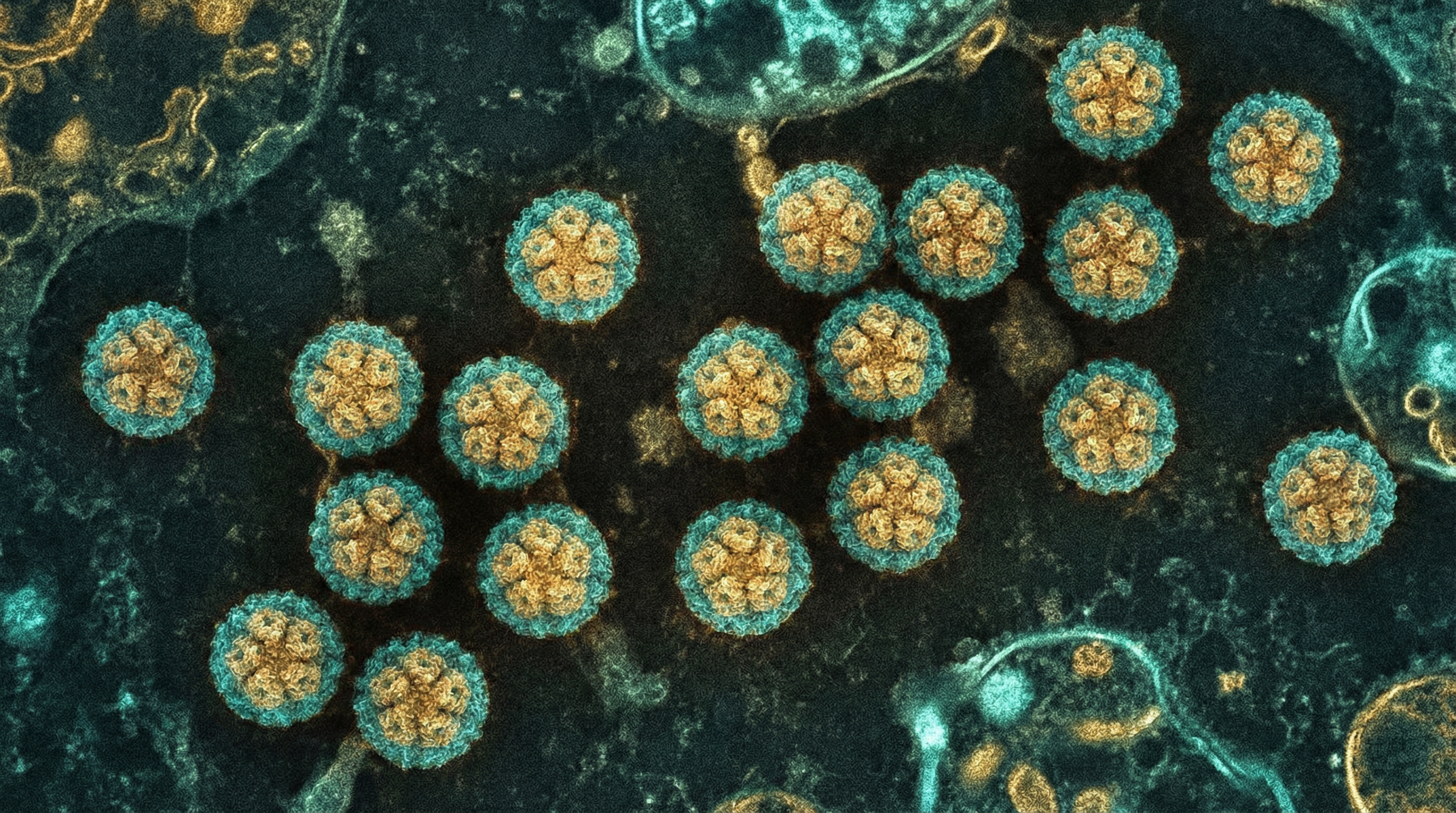

Polyomaviruses have a characteristic structure that includes:

Capsid: A non-enveloped, icosahedral capsid approximately 40-45 nm in diameter, composed of 72 pentameric capsomeres.

Capsid Proteins: The capsid is primarily composed of the major capsid protein VP1, with the minor capsid proteins VP2 and VP3 located internally.

Genome: A circular, double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 5,000 base pairs, which is associated with cellular histones to form a chromatin-like complex (minichromosome) within the virion.

The structure of polyomavirus virions is remarkably stable, allowing them to resist environmental degradation and various disinfection methods, contributing to their persistence and transmission.

Genomic Organization

The polyomavirus genome is compact and efficiently organized, with virtually no non-coding DNA. It is divided into three functional regions:

Early Region: Encodes regulatory proteins expressed before viral DNA replication:

- Large T antigen (LT): A multifunctional protein essential for viral DNA replication and regulation of both viral and cellular gene expression

- Small T antigen (sT): Enhances viral replication and can induce cellular transformation

- In some polyomaviruses, additional T antigen variants (such as middle T, 17kT, or alternative T antigens) are produced through alternative splicing

Late Region: Encodes structural proteins expressed after viral DNA replication:

- VP1: Major capsid protein that forms the outer shell of the virion

- VP2 and VP3: Minor capsid proteins located internally

- Some polyomaviruses (including BKPyV and JCPyV) also encode an agnoprotein, which plays roles in virion assembly and release

Non-coding Control Region (NCCR): Located between the early and late regions, contains:

- Origin of DNA replication

- Promoter and enhancer elements that regulate transcription of both early and late genes

- Binding sites for cellular transcription factors and the viral LT antigen

The NCCR is highly variable between different polyomavirus species and can undergo rearrangements that affect viral replication efficiency and tissue tropism, particularly in BKPyV and JCPyV.

Viral Life Cycle

The polyomavirus life cycle involves several distinct stages:

Attachment and Entry:

- Binding to specific cellular receptors: BKPyV and JCPyV bind to sialylated glycans (gangliosides for BKPyV; serotonin 5-HT2A receptor for JCPyV)

- Entry via endocytosis: BKPyV, SV40, and MCPyV use caveolae-mediated endocytosis, while JCPyV uses clathrin-mediated endocytosis

- Trafficking through the endosomal system to the endoplasmic reticulum

Uncoating and Nuclear Entry:

- Partial disassembly in the endoplasmic reticulum

- Translocation to the cytosol via the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway

- Nuclear import of the viral genome, possibly still associated with some capsid proteins

Early Gene Expression:

- Transcription of the early region by host RNA polymerase II

- Production of T antigens, which manipulate the cellular environment to support viral replication

- LT antigen inactivates tumor suppressor proteins (pRb and p53) and drives cells into S-phase

Viral DNA Replication:

- LT antigen binds to the viral origin of replication

- Formation of a double-hexameric helicase complex

- Recruitment of cellular DNA replication machinery

- Bidirectional replication of the viral genome

Late Gene Expression:

- Activation of the late promoter, possibly facilitated by viral DNA replication

- Production of capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3) and, in some cases, agnoprotein

- Regulation by microRNAs encoded in the late region of some polyomaviruses

Assembly and Release:

- Nuclear import of capsid proteins

- Assembly of virions in the nucleus

- Release through cell lysis or, potentially, non-lytic release mechanisms in some contexts

In permissive cells, this productive cycle leads to the generation of new virions and typically results in cell death. In non-permissive cells, the cycle may be aborted after early gene expression, potentially leading to cellular transformation through the actions of T antigens on cell cycle regulators.

Genetic Diversity and Evolution

Human polyomaviruses display significant genetic diversity:

Species Diversity: At least 13 human polyomavirus species have been identified:

- BK polyomavirus (BKPyV)

- JC polyomavirus (JCPyV)

- Karolinska Institute polyomavirus (KIPyV)

- Washington University polyomavirus (WUPyV)

- Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV)

- Human polyomavirus 6 (HPyV6)

- Human polyomavirus 7 (HPyV7)

- Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV)

- Human polyomavirus 9 (HPyV9)

- MW polyomavirus (MWPyV)

- STL polyomavirus (STLPyV)

- Human polyomavirus 12 (HPyV12)

- New Jersey polyomavirus (NJPyV)

Intraspecies Variation:

- JCPyV has at least seven major genotypes with geographic associations: Types 1 and 4 in Europe and the United States, Type 2 in Asia, and Type 3 in Africa

- BKPyV has four major serotypes (I-IV) with multiple subtypes

- NCCR rearrangements in both BKPyV and JCPyV can arise during viral replication, affecting viral gene expression and replication efficiency

Evolutionary Relationships:

- Human polyomaviruses cluster into three main evolutionary groups:

- BKPyV and JCPyV are closely related to SV40 (SV40 subgroup)

- MCPyV is more closely related to murine polyomavirus (MPyV subgroup)

- The remaining human polyomaviruses form distinct evolutionary lineages

- Co-evolution with their hosts over millions of years has shaped polyomavirus diversity

- Human polyomaviruses cluster into three main evolutionary groups:

The ongoing discovery of new human polyomaviruses suggests that additional species may yet be identified, further expanding our understanding of the diversity of these viruses within the human virome.

Role in Human Microbiome

Human polyomaviruses are widespread components of the human virome, with distinct patterns of tissue tropism, prevalence, and persistence:

Prevalence and Distribution

Seroprevalence:

- BKPyV and JCPyV: 50-80% of adults worldwide show serological evidence of past infection

- MCPyV: 60-80% seroprevalence in adults

- Other human polyomaviruses: Variable seroprevalence, generally increasing with age

Tissue Distribution:

- BKPyV: Primarily detected in the urinary tract (kidney, ureter, bladder) and can be found in urine samples from healthy individuals

- JCPyV: Found in the kidney, urinary tract, and central nervous system, particularly in oligodendrocytes

- MCPyV: Primarily detected on the skin, where it appears to be a common component of the normal skin virome

- Other human polyomaviruses show various tissue tropisms, including respiratory tract (KIPyV, WUPyV), skin (HPyV6, HPyV7, TSPyV), and gastrointestinal tract (MWPyV, STLPyV)

Viral Shedding:

- BKPyV: Intermittently shed in the urine of 5-10% of healthy adults

- JCPyV: Shed in the urine of approximately 30% of healthy adults

- MCPyV: Detected on the skin surface of most individuals

- Shedding rates increase during immunosuppression

Acquisition and Persistence

Primary Infection:

- Most human polyomaviruses are acquired during childhood or early adulthood

- Transmission routes are not fully established but likely include:

- Respiratory route (respiratory droplets, aerosols)

- Oral-fecal route (contaminated food or water)

- Direct contact (particularly for skin-associated polyomaviruses)

- Vertical transmission (mother to child)

- Primary infection is typically asymptomatic or causes mild, non-specific symptoms

Latency and Persistence:

- Following primary infection, polyomaviruses establish latent infections in specific tissues

- Viral genomes persist as episomes (circular extrachromosomal DNA) in the nucleus of infected cells

- Minimal viral gene expression occurs during latency, helping to evade immune detection

- Periodic subclinical reactivation may occur, leading to viral shedding without disease

Reactivation:

- Significant reactivation typically occurs only during immunosuppression

- Factors promoting reactivation include:

- Iatrogenic immunosuppression (transplant recipients, immunosuppressive therapies)

- HIV/AIDS

- Hematological malignancies

- Advanced age

- Pregnancy (for BKPyV)

- Reactivation leads to increased viral replication and shedding, potentially causing disease

Integration with Bacterial Microbiome

The interactions between human polyomaviruses and the bacterial microbiome remain largely unexplored, but emerging evidence suggests potential relationships:

Co-localization:

- Polyomaviruses co-exist with bacterial communities in various body sites, including the urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, and skin

- The composition of the local bacterial microbiome may influence polyomavirus replication and persistence

Potential Interactions:

- Bacterial metabolites or components might affect polyomavirus replication or gene expression

- Polyomavirus infection might alter the local microenvironment, potentially affecting bacterial communities

- Co-infections with polyomaviruses and bacteria might have synergistic effects on pathogenesis

Research Challenges:

- The low abundance of polyomaviruses relative to bacteria makes studying these interactions technically challenging

- The potential for indirect interactions through effects on host physiology adds complexity

- Longitudinal studies examining both viral and bacterial components of the microbiome are needed

Understanding the role of human polyomaviruses as members of the human virome, including their interactions with other microbiome components, represents an important frontier in microbiome research with potential implications for human health.

Health Implications

Human polyomaviruses can cause a spectrum of health effects, ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe disease, depending on the virus, host factors, and context:

Asymptomatic Infections

Prevalence:

- The vast majority of polyomavirus infections in immunocompetent individuals are asymptomatic

- Periodic subclinical reactivation and shedding occur without clinical consequences

- These asymptomatic infections represent the normal state of virus-host coexistence

Immune Control:

- Effective immune responses, particularly virus-specific T cells, maintain viral latency

- Neutralizing antibodies may help prevent reinfection or limit viral spread during reactivation

- Innate immune mechanisms may also contribute to controlling viral replication

Potential Benefits:

- Some researchers have proposed that persistent viral infections, including polyomaviruses, might provide benefits to the host through "viral symbiosis"

- Potential mechanisms include training of the immune system and competition with more pathogenic viruses

- However, evidence for beneficial effects of polyomavirus infections remains limited

BK Virus-Associated Diseases

BK Virus Nephropathy (BKVN):

- Occurs in 1-10% of kidney transplant recipients

- Results from extensive BKPyV replication in renal tubular epithelial cells

- Characterized by viral cytopathic effects, inflammation, and tubular atrophy

- Can lead to progressive renal dysfunction and graft loss if not recognized and managed early

- Diagnosis relies on measuring BK viral load in blood and urine, followed by kidney biopsy

- Management primarily involves reducing immunosuppression

BK Virus-Associated Hemorrhagic Cystitis:

- Occurs in 5-15% of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients

- Characterized by hemorrhagic inflammation of the bladder

- Presents with dysuria, hematuria, and sometimes severe hemorrhage

- Treatment is mainly supportive, with consideration of cidofovir in severe cases

Other BKPyV-Associated Conditions:

- Ureteral stenosis in kidney transplant recipients

- Rare cases of encephalitis, pneumonitis, or vasculopathy

- Possible association with certain cancers, though causality remains unestablished

JC Virus-Associated Diseases

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML):

- Severe demyelinating disease of the central nervous system

- Results from JCPyV replication in oligodendrocytes, leading to their destruction

- Occurs primarily in severely immunocompromised individuals:

- HIV/AIDS patients (though incidence has decreased with effective antiretroviral therapy)

- Recipients of certain immunomodulatory therapies (natalizumab, rituximab, fingolimod)

- Patients with hematological malignancies or after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- Presents with progressive neurological deficits, including motor weakness, visual changes, cognitive impairment, and seizures

- Diagnosis based on clinical presentation, MRI findings, and detection of JCPyV in cerebrospinal fluid

- High mortality rate (30-50%) and significant morbidity among survivors

- Management focuses on immune reconstitution when possible

JC Virus Granule Cell Neuronopathy:

- Rare condition characterized by cerebellar atrophy and cerebellar dysfunction

- Caused by JCPyV infection of cerebellar granule cell neurons

- Considered a distinct entity from classical PML

Other Potential Associations:

- JCPyV DNA has been detected in various human cancers, but causality remains controversial

- Possible role in certain kidney diseases, though evidence is limited

Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancer

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC):

- Rare but aggressive skin cancer with high mortality rate

- MCPyV is causally implicated in approximately 80% of MCC cases

- Carcinogenesis involves:

- Clonal integration of MCPyV DNA into the host genome

- Truncating mutations in the viral large T antigen that eliminate its helicase domain while preserving oncogenic domains

- Expression of viral oncoproteins (truncated LT and sT antigens)

- Additional host genetic alterations

- MCPyV-positive MCCs typically have better prognosis than MCPyV-negative tumors

- Risk factors include advanced age, immunosuppression, and UV exposure

Oncogenic Mechanisms:

- MCPyV LT antigen binds and inactivates the tumor suppressor Rb, promoting cell cycle progression

- MCPyV sT antigen inhibits the cellular ubiquitin ligase SCF^Fbw7, stabilizing LT antigen and cellular oncoproteins

- sT antigen also activates cap-dependent translation through interactions with 4E-BP1

- These mechanisms drive cellular proliferation and survival

Therapeutic Implications:

- MCPyV oncoproteins represent potential targets for immunotherapy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown promising results in treating MCC

- Virus-specific T cell therapies are under investigation

Other Human Polyomavirus-Associated Conditions

Trichodysplasia Spinulosa:

- Rare skin disease characterized by follicular papules and spines on the face

- Caused by TSPyV reactivation in immunocompromised individuals

- Affects hair follicle inner root sheath cells

Potential Associations Under Investigation:

- KIPyV and WUPyV: Possible role in respiratory disease

- HPyV6 and HPyV7: Reported associations with pruritic skin rashes in immunocompromised patients

- HPyV9: Detected in skin and blood samples, but disease associations remain unclear

- MWPyV and STLPyV: Found in gastrointestinal samples, potential role in gastrointestinal disease under investigation

Understanding the full spectrum of health implications associated with human polyomaviruses continues to evolve as research advances, with potential for discovery of additional disease associations as well as refinement of our understanding of established relationships.

Metabolic Activities

The metabolic activities of human polyomaviruses are intimately linked to their replication strategies and interactions with host cells:

Viral Replication Strategy

Dependence on Host Machinery:

- Polyomaviruses have small genomes and encode few proteins, relying heavily on host cell machinery for replication

- They do not encode their own DNA polymerases or most other enzymes required for DNA replication

- Instead, they manipulate the host cell environment to provide necessary factors

Cell Cycle Manipulation:

- LT antigen inactivates the retinoblastoma protein family (pRb, p107, p130) by binding to their pocket domains

- This releases E2F transcription factors, driving expression of S-phase genes

- The resulting cellular environment provides the DNA replication machinery needed for viral genome replication

- LT antigen also inactivates p53, preventing apoptosis that might otherwise be triggered by unscheduled DNA synthesis

Viral DNA Replication:

- LT antigen binds to the viral origin of replication as a double hexamer

- It functions as a helicase, unwinding the viral DNA

- It recruits host replication proteins, including:

- DNA polymerase α-primase

- Replication protein A (RPA)

- Topoisomerase I

- Replication factor C (RFC)

- Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)

- Bidirectional replication proceeds using the host cell's DNA synthesis machinery

Metabolic Reprogramming

Polyomavirus infection induces significant changes in cellular metabolism:

Energy Metabolism:

- Increased glucose uptake and glycolysis

- Enhanced mitochondrial activity

- These changes provide energy for viral replication and biosynthetic precursors

Nucleotide Metabolism:

- Upregulation of nucleotide biosynthesis pathways

- Increased activity of ribonucleotide reductase

- These changes ensure adequate supply of deoxynucleotides for viral DNA synthesis

Lipid Metabolism:

- Alterations in membrane lipid composition

- Changes in lipid signaling pathways

- These modifications may facilitate viral entry, trafficking, and assembly

Protein Synthesis:

- Enhanced cap-dependent translation

- MCPyV sT antigen directly promotes protein synthesis through interactions with 4E-BP1

- Increased protein synthesis supports production of viral proteins and host factors required for replication

Viral Protein Functions

The metabolic activities of specific polyomavirus proteins include:

Large T Antigen:

- Functions as a helicase during viral DNA replication

- Binds to and inactivates tumor suppressors pRb and p53

- Interacts with cellular DNA replication factors

- Regulates viral gene expression

- May alter host cell gene expression

Small T Antigen:

- Inhibits protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), affecting multiple signaling pathways

- MCPyV sT activates cap-dependent translation through 4E-BP1

- Enhances LT antigen-mediated viral DNA replication

- Promotes cell cycle progression and cellular transformation

Agnoprotein (in BKPyV and JCPyV):

- Facilitates virion assembly and release

- May regulate viral gene expression

- Interacts with host cell proteins, potentially affecting cellular functions

VP1, VP2, and VP3:

- Form the viral capsid

- VP1 mediates attachment to cellular receptors

- VP2 and VP3 may play roles in viral entry and uncoating

Host Cell Metabolic Responses

Host cells respond to polyomavirus infection with various metabolic adaptations:

Stress Responses:

- Activation of the DNA damage response

- Endoplasmic reticulum stress response

- These responses may initially serve as antiviral mechanisms but can be co-opted by the virus

Autophagy:

- Polyomavirus infection can modulate autophagy

- JCPyV and BKPyV may induce autophagy to support their replication

- Autophagy may also represent a host defense mechanism against infection

Interferon Response:

- Polyomavirus infection can trigger interferon production

- Interferons induce metabolic changes as part of the antiviral state

- Viral proteins may counteract these responses to facilitate replication

Understanding the metabolic activities of human polyomaviruses provides insights into their replication strategies and pathogenic mechanisms, potentially revealing targets for therapeutic intervention in polyomavirus-associated diseases.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical relevance of human polyomaviruses encompasses their role in disease, approaches to diagnosis and management, and implications for public health:

Diagnostic Approaches

BK Virus Nephropathy (BKVN):

- Screening: Quantitative PCR for BKPyV DNA in plasma and urine

- Diagnostic thresholds: >10,000 copies/mL in plasma or >10^7 copies/mL in urine suggest significant reactivation

- Definitive diagnosis: Kidney biopsy with characteristic histopathological findings and immunohistochemistry for SV40 T antigen (cross-reacts with BKPyV)

- Monitoring: Regular screening of high-risk patients (kidney transplant recipients) is recommended

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML):

- Neuroimaging: MRI showing characteristic white matter lesions

- CSF analysis: PCR for JCPyV DNA (sensitivity ~80%)

- Brain biopsy: Reserved for cases with negative CSF PCR but high clinical suspicion

- Risk stratification: Anti-JCV antibody index in patients receiving natalizumab

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC):

- Histopathology: Characteristic appearance with immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A

- MCPyV detection: PCR for viral DNA or immunohistochemistry for MCPyV LT antigen

- Distinction between MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC has prognostic implications

Emerging Diagnostic Technologies:

- Digital droplet PCR for improved sensitivity and quantification

- Next-generation sequencing for viral genome characterization

- Multiplex assays for simultaneous detection of multiple human polyomaviruses

- Serological assays using virus-like particles for antibody detection

Management Strategies

BK Virus Nephropathy:

- Primary approach: Reduction of immunosuppression

- Stepwise reduction typically begins with antiproliferative agents (mycophenolate mofetil)

- Adjunctive therapies with limited evidence:

- Cidofovir (low-dose)

- Leflunomide

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin)

- Retransplantation is generally successful after viral clearance

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy:

- Immune reconstitution: Reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy when possible

- HIV-associated PML: Optimization of antiretroviral therapy

- Natalizumab-associated PML: Plasma exchange to accelerate drug clearance

- Experimental approaches:

- Cidofovir (limited evidence)

- Mirtazapine (5-HT2A receptor antagonist)

- Mefloquine

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- Adoptive T cell therapy

Merkel Cell Carcinoma:

- Surgery: Wide local excision for localized disease

- Radiation therapy: Adjuvant treatment after surgery or primary treatment for unresectable disease

- Systemic therapy for advanced disease:

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, avelumab)

- Chemotherapy (platinum-based combinations)

- Emerging approaches:

- MCPyV-specific T cell therapies

- Targeted therapies based on molecular characteristics

Other Polyomavirus-Associated Conditions:

- Trichodysplasia spinulosa: Topical cidofovir, reduction of immunosuppression

- BK virus-associated hemorrhagic cystitis: Supportive care, cidofovir in severe cases

- Preventive strategies: Screening and preemptive intervention for high-risk patients

Public Health Implications

Prevalence and Burden:

- BKPyV nephropathy affects 1-10% of kidney transplant recipients

- PML incidence has decreased in HIV/AIDS with effective antiretroviral therapy but increased with certain immunomodulatory therapies

- MCC incidence is rising, possibly due to aging population, increased UV exposure, and improved diagnosis

Risk Assessment and Prevention:

- Stratification of patients based on risk factors (immunosuppression, serological status)

- Screening protocols for high-risk populations

- Monitoring for viral reactivation to enable early intervention

- No vaccines currently available for human polyomaviruses

Healthcare Resource Utilization:

- Significant costs associated with polyomavirus-associated diseases

- Increased hospitalization and specialized care requirements

- Impact on organ transplantation outcomes and practices

Research Priorities:

- Development of effective antiviral therapies

- Improved diagnostic and monitoring approaches

- Better understanding of risk factors for disease progression

- Investigation of potential additional disease associations

The clinical relevance of human polyomaviruses continues to evolve as our understanding of their biology and pathogenesis improves, with ongoing efforts to develop more effective diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic approaches for polyomavirus-associated diseases.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Human polyomaviruses interact with other components of the human microbiome, including bacteria, fungi, and other viruses, with potential implications for health and disease:

Interactions with Other Viruses

Co-infections with HIV:

- HIV-induced immunosuppression is a major risk factor for JCPyV reactivation and PML

- HIV may directly enhance JCPyV replication through interactions between HIV Tat protein and the JCPyV NCCR

- BKPyV reactivation is also more common in HIV-infected individuals

- Effective antiretroviral therapy has reduced the incidence of polyomavirus-associated diseases in HIV patients

Interactions with Herpesviruses:

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BKPyV co-infection is common in kidney transplant recipients

- Some studies suggest that CMV infection may increase the risk of BKPyV reactivation

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and JCPyV co-infection has been reported in some PML cases

- Herpes simplex virus proteins may transactivate JCPyV gene expression in vitro

Interactions with Papillomaviruses:

- MCPyV and human papillomaviruses (HPVs) can co-infect the skin

- Potential for functional interactions, though these remain largely unexplored

- Both virus families encode proteins that target similar cellular pathways (e.g., pRb inactivation)

Interactions with Hepatitis Viruses:

- Hepatitis B and C infections are associated with increased risk of BKPyV reactivation

- Mechanisms may involve immune dysfunction and/or direct viral interactions

- Co-management challenges in transplant recipients with both hepatitis and polyomavirus infections

Interactions with Bacteria

Urinary Tract Microbiome:

- BKPyV primarily infects the urinary tract, where it coexists with the urinary microbiome

- Changes in urinary microbiome composition might influence BKPyV reactivation

- Urinary tract infections and BKPyV reactivation can co-occur in kidney transplant recipients

Gut Microbiome:

- Several human polyomaviruses (JCPyV, BKPyV, MWPyV, STLPyV) can be detected in stool samples

- Potential interactions with gut bacteria remain largely unexplored

- Gut microbiome alterations during immunosuppression might influence polyomavirus reactivation

Skin Microbiome:

- MCPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, and TSPyV are found on the skin, coexisting with the skin microbiome

- Skin bacteria might influence the local environment in ways that affect polyomavirus replication

- Bacterial dysbiosis and polyomavirus reactivation might synergistically contribute to skin conditions

Respiratory Tract Microbiome:

- KIPyV and WUPyV are primarily detected in respiratory samples

- Potential interactions with respiratory bacteria in health and disease

- Co-detection with bacterial pathogens has been reported, though causal relationships remain unclear

Interactions with Fungi

Limited Evidence:

- Few studies have directly examined interactions between human polyomaviruses and fungi

- Both can co-exist in various body sites, particularly the skin and respiratory tract

Immunosuppression Context:

- Patients at risk for polyomavirus reactivation are also at risk for fungal infections

- Management challenges when both occur simultaneously

- Potential for indirect interactions through effects on host immunity

Polymicrobial Disease Concepts

Dysbiosis and Viral Reactivation:

- Alterations in the microbiome might create conditions favorable for polyomavirus reactivation

- Inflammation associated with dysbiosis might trigger viral reactivation

- Changes in local metabolites might influence viral replication

Immune Modulation:

- The microbiome shapes local and systemic immune responses

- These immune effects might influence control of polyomavirus infections

- Probiotics or microbiome-targeted therapies might potentially modulate polyomavirus reactivation

Diagnostic Challenges:

- Distinguishing between the contributions of different microorganisms to disease

- Interpreting the significance of polyomavirus detection in polymicrobial contexts

- Need for comprehensive diagnostic approaches that consider multiple potential pathogens

Therapeutic Implications:

- Potential for microbiome-targeted interventions to influence polyomavirus infections

- Consideration of polymicrobial interactions in treatment strategies

- Challenges in managing multiple concurrent infections in immunocompromised hosts

Understanding the complex interactions between human polyomaviruses and other microorganisms represents an emerging area of research with potential implications for the diagnosis, prevention, and management of polyomavirus-associated diseases.

Research Significance

Human polyomaviruses continue to be the subject of intensive research, with several key areas of current and future significance:

Virome Characterization

Discovery of New Polyomaviruses:

- Thirteen human polyomaviruses identified to date, with potential for additional discoveries

- Metagenomic approaches enabling detection of novel viruses

- Characterization of tissue and host specificity of newly discovered viruses

Prevalence and Distribution:

- Improved understanding of the global distribution of human polyomaviruses

- Age-related patterns of infection and seroprevalence

- Variations in viral strains and genotypes across populations

Viral Persistence and Latency:

- Mechanisms of establishing and maintaining latent infection

- Factors controlling periodic reactivation

- Cellular reservoirs during latency

Pathogenesis and Disease Associations

Oncogenic Mechanisms:

- Detailed understanding of how MCPyV contributes to Merkel cell carcinoma

- Investigation of potential roles of other human polyomaviruses in cancer

- Comparative studies with other oncogenic viruses

Neurotropic Disease:

- Factors determining JCPyV neurotropism and PML development

- Novel therapeutic approaches for PML

- Potential roles of polyomaviruses in other neurological conditions

Kidney Disease:

- Mechanisms of BKPyV-associated nephropathy

- Biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response

- Preventive strategies for high-risk patients

Emerging Disease Associations:

- Investigation of potential roles of recently discovered polyomaviruses in human disease

- Long-term consequences of persistent polyomavirus infection

- Interactions with aging and age-related diseases

Immunology and Host Response

Immune Control Mechanisms:

- Role of innate and adaptive immunity in controlling polyomavirus infections

- Factors leading to immune escape and reactivation

- Development of immunotherapeutic approaches

Immunocompromised Host:

- Risk stratification for polyomavirus-associated diseases

- Balancing immunosuppression and viral control in transplant recipients

- Novel approaches to enhance virus-specific immunity without triggering rejection

Vaccine Development:

- Potential for preventive vaccines against human polyomaviruses

- Therapeutic vaccines for established infections

- Technical challenges in vaccine development and implementation

Technological Advances

Diagnostic Tools:

- Improved molecular diagnostics for viral detection and quantification

- Biomarkers for disease risk and progression

- Point-of-care testing for resource-limited settings

Therapeutic Development:

- Antiviral agents targeting polyomavirus replication

- Immunotherapeutic approaches for polyomavirus-associated diseases

- Targeted therapies based on molecular understanding of pathogenesis

Research Models:

- Development of improved cell culture systems for studying human polyomaviruses

- Animal models that recapitulate aspects of human disease

- Organoid and tissue culture systems for studying virus-host interactions

Public Health and Clinical Applications

Screening and Monitoring Protocols:

- Evidence-based approaches for screening high-risk populations

- Optimal monitoring strategies for early detection of viral reactivation

- Cost-effective implementation in various healthcare settings

Treatment Guidelines:

- Standardized approaches to managing polyomavirus-associated diseases

- Personalized medicine approaches based on viral and host factors

- Integration of new therapies as they become available

Global Health Perspectives:

- Burden of polyomavirus-associated diseases in different regions

- Access to diagnostics and treatments in resource-limited settings

- Impact of polyomavirus infections in the context of other global health challenges

The research significance of human polyomaviruses extends across basic virology, immunology, oncology, and clinical medicine, with ongoing discoveries continuing to shape our understanding of these ubiquitous components of the human virome and their impact on human health.

Conclusion

Human polyomaviruses represent a fascinating group of viruses that exemplify the complex relationships between the human virome and health. From their ubiquitous presence as largely asymptomatic components of the normal human virome to their potential to cause severe disease under specific circumstances, these viruses highlight the delicate balance between commensalism and pathogenicity in host-virus interactions.

The discovery of Merkel cell polyomavirus as the first human polyomavirus directly linked to cancer marked a significant milestone in our understanding of viral oncogenesis and expanded the small group of known human tumor viruses. Meanwhile, the well-established associations of BK virus with nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients and JC virus with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in immunocompromised individuals underscore the clinical importance of these viruses in vulnerable populations.

As research continues to advance, our understanding of human polyomaviruses will undoubtedly deepen, potentially revealing additional species, clarifying disease associations, and leading to improved approaches for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of polyomavirus-associated diseases. The study of these viruses not only contributes to our knowledge of specific clinical conditions but also provides broader insights into fundamental aspects of virology, immunology, and the complex ecosystem of the human microbiome.

In an era of increasing appreciation for the role of the microbiome in human health, human polyomaviruses serve as an important reminder that the virome represents an integral, though often overlooked, component of this ecosystem. Continued research into these fascinating viruses promises to yield valuable insights with implications extending far beyond the specific viruses themselves.