Porphyromonas gingivalis

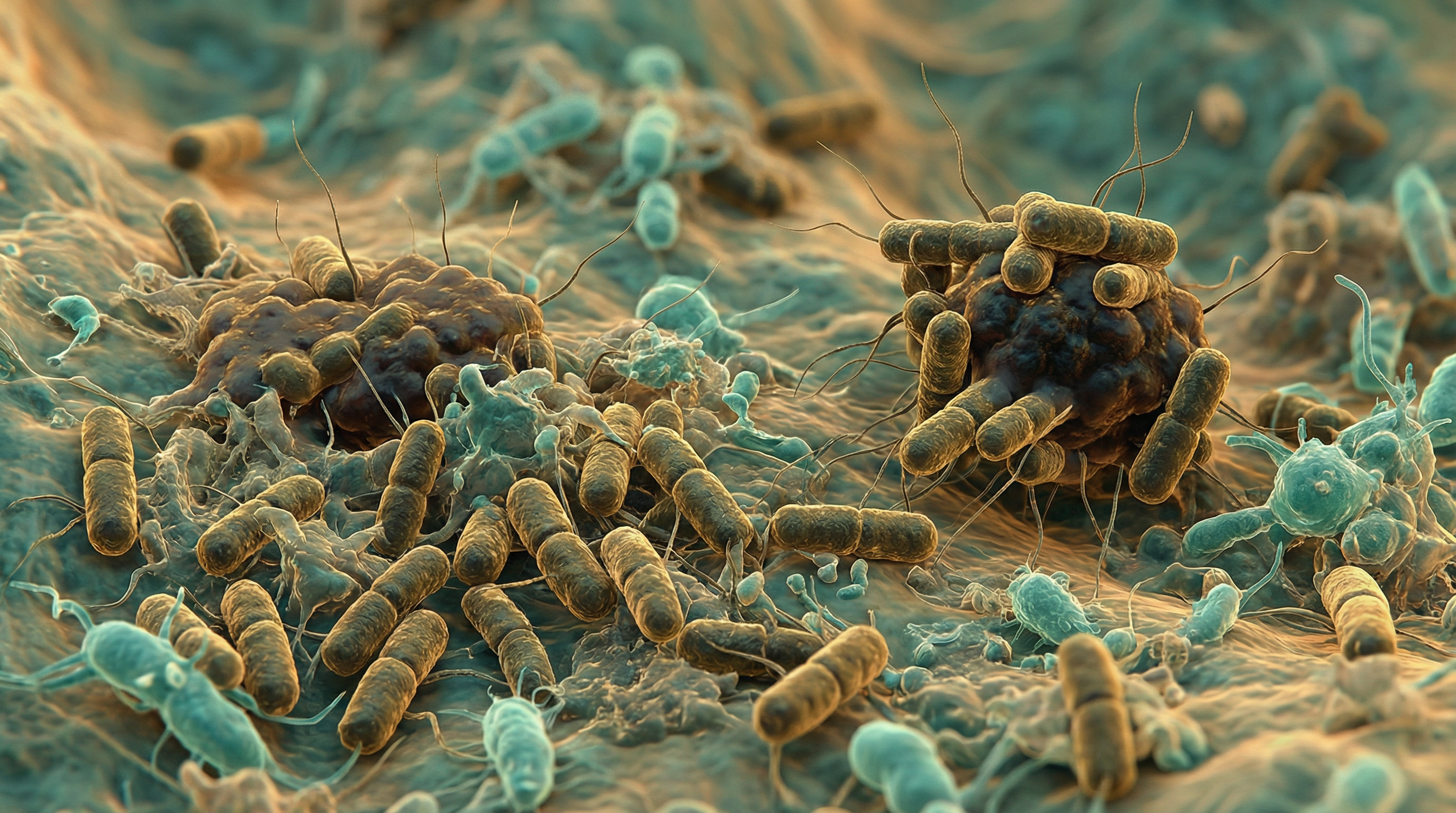

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a Gram-negative, anaerobic, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterium belonging to the phylum Bacteroidetes. It is recognized as a keystone pathogen in the development of chronic periodontitis, a severe inflammatory disease affecting the tissues supporting the teeth. This black-pigmented bacterium produces a myriad of virulence factors that cause destruction to periodontal tissues either directly or by modulating the host inflammatory response. Beyond its role in oral health, P. gingivalis has been implicated in various systemic conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, gastric cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease.

Key Characteristics

P. gingivalis is characterized by several distinctive features that contribute to its pathogenicity and survival in the oral environment:

Gram-negative cell wall structure: Contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that triggers inflammatory responses in the host.

Obligate anaerobe: Requires an oxygen-free environment for growth, thriving in the anaerobic conditions of deep periodontal pockets.

Black pigmentation: Produces dark pigmentation when grown on blood agar due to its ability to accumulate heme on its cell surface, which serves as an iron source and provides protection against oxidative stress.

Non-motile: Lacks flagella but possesses fimbriae that facilitate adhesion to surfaces.

Asaccharolytic metabolism: Cannot ferment carbohydrates for energy; instead relies on peptides and amino acids derived from protein degradation.

Acid resistance: Unlike many oral bacteria, P. gingivalis can survive acidic environments, allowing it to potentially migrate from the oral cavity to the stomach and intestines.

Biofilm formation: Capable of forming and participating in complex multispecies biofilms, which enhances its survival and virulence.

These characteristics enable P. gingivalis to colonize the subgingival environment, evade host defenses, and cause tissue destruction, ultimately contributing to the progression of periodontal disease.

Role in the Human Microbiome

P. gingivalis primarily inhabits the human oral cavity, specifically the subgingival region. While it can be detected in healthy individuals, its abundance significantly increases in individuals with periodontal disease. In the context of the oral microbiome, P. gingivalis functions as a keystone pathogen, meaning that even at low abundance, it can orchestrate inflammatory disease by remodeling a normally benign microbiota into a dysbiotic one.

The ecological role of P. gingivalis in the oral microbiome includes:

Dysbiosis induction: P. gingivalis can disrupt the homeostasis of the oral microbiome, leading to an imbalance that favors pathogenic bacteria over commensal ones.

Biofilm participation: It integrates into dental plaque biofilms, contributing to their structural integrity and resistance to antimicrobial agents.

Interspecies interactions: P. gingivalis engages in complex relationships with other oral bacteria, including metabolic cooperation, signaling, and horizontal gene transfer.

Niche modification: Through its various virulence factors, P. gingivalis can modify the local environment to favor its own growth and that of other periodontal pathogens.

Beyond the oral cavity, recent research has demonstrated that P. gingivalis can translocate to other body sites. It has been detected in the bloodstream following dental procedures or even routine activities like brushing and flossing in individuals with periodontal disease. This bacteremia allows P. gingivalis to potentially colonize distant tissues, including the liver, placenta, and coronary arteries. Additionally, being acid-resistant, P. gingivalis can survive passage through the stomach and has been found to alter the gut microbiome composition when introduced orally in experimental models.

Health Implications

Periodontal Disease

The primary pathological role of P. gingivalis is in the initiation and progression of periodontal disease. Chronic periodontitis is characterized by inflammation of the gingiva, destruction of periodontal ligaments, resorption of alveolar bone, and eventually tooth loss if left untreated. P. gingivalis contributes to this disease process through:

Direct tissue damage: Proteases and other enzymes produced by P. gingivalis can directly degrade host tissues.

Immune dysregulation: P. gingivalis can both stimulate inflammatory responses and suppress certain aspects of immunity, leading to a dysregulated host response that causes collateral tissue damage.

Biofilm formation: By participating in dental plaque biofilms, P. gingivalis contributes to a protected environment where bacteria can proliferate and resist host defenses and antimicrobial treatments.

Bone resorption: P. gingivalis can induce osteoclast activity, leading to alveolar bone loss, a hallmark of advanced periodontitis.

Systemic Conditions

Emerging evidence (2020-2025) provides strong mechanistic links between P. gingivalis and systemic diseases:[1][4]

Alzheimer's Disease

Detection and Risk:

- P. gingivalis DNA and gingipains detected in >90% of postmortem AD brains

- Oral bacteria in brain: OR = 10.68; P. gingivalis specifically: OR = 6.84

- Periodontitis increases AD risk 1.7-fold; 6-fold cognitive decline acceleration over 6 months

Mechanisms:

- Translocation: Hematogenous spread, trigeminal nerve pathway, gut-brain axis, OMV delivery

- BBB Disruption: Mfsd2a/Caveolin-1 mediated transcytosis; gingipains cleave PECAM-1, β1-integrin, tight junction proteins

- Aβ Pathology: Upregulates APP, BACE1, presenilins; downregulates neprilysin (Aβ-degrading enzyme)

- Tau Pathology: Hyperphosphorylation at Thr181, Thr231; GSK-3β and caspase-3 activation; PP2A suppression

Diabetes-Cognitive Impairment[2][5]

- Aggravates cognitive dysfunction in T2DM via gut-microbiota-SCFA-Olfr78 axis

- Significant reduction in synaptic proteins (SYN, PSD-95, FXR1, FXR2, GluN2B, GluA2)

- Increased microglial activation (Iba1, IL-1β, iNOS, COX2)

Cardiovascular Disease

- P. gingivalis DNA in atherosclerotic plaques

- Gingipain cleavage of apolipoproteins (apoE, apoB-100); HDL oxidation

- Endothelial dysfunction via eNOS inhibition (ROCK pathway)

- Gingipain activation of prothrombin to thrombin (thrombosis)

- Treatment: KYT-1 gingipain inhibitor (1 µM IV) significantly reduced atherosclerotic lesions

Cancer Associations

- Oral SCC: Detected in 50-80% with severe periodontitis; EMT via PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β

- Esophageal Cancer: 61% ESCC tissues positive vs 0% normal mucosa

- Colorectal Cancer: UCHL3 upregulation activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR

- Pancreatic Cancer: miR-21/PTEN axis; immunosuppressive microenvironment

Rheumatoid Arthritis

- PPAD-mediated citrullination induces anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)

- M1 macrophage activation; increased ROS and succinate

These associations highlight the potential far-reaching implications of P. gingivalis beyond its role in periodontal disease, emphasizing the importance of oral health in overall systemic health.

Metabolic Activities

P. gingivalis exhibits a specialized metabolism adapted to its niche in the subgingival environment:

Asaccharolytic metabolism: Unlike many oral bacteria, P. gingivalis cannot utilize carbohydrates as a primary energy source. Instead, it relies on the degradation of proteins and peptides for nutrition.

Proteolytic activity: P. gingivalis produces various proteases, particularly gingipains, which break down host proteins into peptides and amino acids that the bacterium can utilize for growth.

Heme acquisition: P. gingivalis requires heme for growth and has developed sophisticated mechanisms to acquire this essential nutrient from the host, including hemolysins and hemagglutinins.

Amino acid fermentation: After protein degradation, P. gingivalis ferments amino acids to produce energy, generating short-chain fatty acids and ammonia as byproducts.

Lipid metabolism: P. gingivalis can modify host lipids, which may contribute to inflammatory processes and tissue destruction.

Quorum sensing: P. gingivalis participates in bacterial communication through quorum sensing, which regulates gene expression based on population density and influences biofilm formation and virulence factor production.

These metabolic activities not only support the growth and survival of P. gingivalis but also contribute to its pathogenicity by generating toxic byproducts, modifying the local environment, and providing mechanisms to evade host defenses.

Virulence Factors

P. gingivalis produces an extensive array of virulence factors that contribute to its pathogenicity:[3][1]

Gingipains (Primary Virulence Factors)

The cysteine proteases are essential for P. gingivalis pathogenicity:

- Types: RgpA, RgpB (arginine-specific), Kgp (lysine-specific)

- Functions:

- Nutrient acquisition (heme from hemoglobin)

- Extracellular matrix degradation

- Host immune system dysregulation

- Complement system manipulation

- Antibody and cytokine degradation

- Macrophage Evasion: Gingipain-null mutants cleared by 53 hours vs W83 survived >53 hours; 3-fold greater phagosome acidification in mutants

- Viral Activation: Rgp cleaves influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA0 at Arg329), activating viral entry[4][2]

- OMV Abundance: Gingipains with C-terminal domains are 3-5x more abundant in outer membrane vesicles than in bacterial cells

Type IX Secretion System (T9SS)

- Components: 18 protein components including PorL/PorM (proton motor), PorV (shuttle), Sov (pore)

- Cargo: >30 exported proteins including gingipains and PPAD

- Regulation: Ltp1-Ptk1 tyrosine phosphorylation axis controls gingipain processing

Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs)[5][3]

- Size: 20-250 nm nanospherical structures

- Production: ~2000 OMVs per bacterium during stabilization growth

- Invasion Efficiency: 70-90% in gingival epithelial cells vs 20-50% for parent bacteria

- Cargo: Gingipains, LPS, PPAD, Fimbriae, OmpA, sRNA23392

- Systemic Delivery: Reach distant tissues via bloodstream or trigeminal nerve

Fimbriae

- Major (FimA): Interspecies attachment via GAPDH residues 166-183; multiple genotypes with varying virulence

- Minor (Mfa1): Interacts with SspA/B proteins; C-terminal BAR domain for interspecies interactions

Peptidylarginine Deiminase (PPAD)

- Function: Citrullination - converts arginine to citrulline

- Consequences: Neutralizes antimicrobial peptides; facilitates NET escape; induces autoimmune responses in rheumatoid arthritis

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

- Types: O-LPS (standard), A-LPS (anionic, anchors T9SS cargo)

- Immune Evasion: Lipid A-modifying enzymes (LpxE, LpxF, LpxR) create TLR4 antagonists

These virulence factors work in concert to enable P. gingivalis to colonize the oral cavity, evade host defenses, acquire nutrients, and cause tissue destruction, ultimately contributing to the pathogenesis of periodontal disease and potentially systemic conditions.

Immune Evasion Mechanisms

P. gingivalis employs sophisticated strategies to evade host immune responses:[6][6]

C5aR-TLR2 Crosstalk

- Gingipains cleave C5 → active C5a → C5aR1 activation

- Uncouples bacterial killing from inflammation via MyD88 degradation

- PI3K inhibition reduced P. gingivalis by ~1.5 log10 units (97% reduction)

- Cross-protection: P. gingivalis survival enhanced by 3 log10 for bystander F. nucleatum

CD47-TSP1 Axis

- Fimbriae activate TLR2-CD47 complex → PI3K/AKT pathway

- TSP-1 secretion suppresses neutrophil ROS and bactericidal activity

- TSP-1 (100 ng/mL) reduced neutrophil ROS to background levels

- Therapeutic: TAX2 peptide (100 μM) completely restored bactericidal activity

Zbp1-Mediated PANoptosis[7][7]

- P. gingivalis induces mitochondrial stress → mtDNA release → Zbp1 activation

- Triggers pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis simultaneously

- Therapeutic: Salvianolic acid B binds Zbp1 (binding energy -7.2 kcal/mol); delivered via microneedle patches

Clinical Relevance

Therapeutic Advances (2020-2025)

Gingipain Inhibitors:

- COR-388 (Atuzaginstat): Discontinued Phase 2/3 due to hepatotoxicity; slowed cognitive decline by 57% in P. gingivalis-positive AD patients

- LHP588: Phase 2 trials ongoing

- KYT-1: Rgp-specific; 5 μM blocked influenza HA cleavage; 1 µM IV reduced atherosclerotic lesions

Complement-Targeted Therapy:

- Compstatin analog Cp40 (AMY-101): Protected against periodontitis in non-human primates

CD47-TSP1 Inhibitors:

- TAX2 peptide: Restores neutrophil bactericidal activity

- CD47 neutralizing antibodies: Improved P. gingivalis clearance

Natural Compounds:

- Salvianolic acid B: Zbp1 inhibitor via microneedle delivery

- Probiotics: Nisin mitigated brain microbiome dysbiosis; reduced Aβ and tau

Keystone Pathogen Clinical Implications

- Diagnosis: Detection as biomarker for periodontal disease and systemic risk

- Community Engineering: Shift from eradication to restoring homeostasis

- Precision Medicine: Strain-specific therapeutics based on genotype

- Oral-Systemic Connection: Periodontal treatment improves diabetes, reduces cognitive decline

- Vaccine Development: OMV immunization shows sustained IgG/S-IgA responses up to 28 weeks

From a clinical management perspective, controlling P. gingivalis infection typically involves a combination of mechanical debridement (scaling and root planing), antimicrobial therapy (local or systemic), and in severe cases, surgical intervention. Patient education on oral hygiene practices is also crucial for preventing recolonization.

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

P. gingivalis engages in complex interactions with other members of the oral microbiome:

Synergistic relationships: P. gingivalis forms synergistic relationships with other periodontal pathogens, such as Treponema denticola and Tannerella forsythia, collectively known as the "red complex." These bacteria enhance each other's virulence and contribute to a more severe disease phenotype.

Metabolic cooperation: P. gingivalis can engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other bacteria, where byproducts of one species serve as nutrients for another, enhancing the survival of the microbial community as a whole.

Biofilm architecture: Within dental plaque biofilms, P. gingivalis occupies specific niches and contributes to the overall architecture and stability of the biofilm.

Horizontal gene transfer: P. gingivalis can exchange genetic material with other bacteria, potentially acquiring new virulence traits or antibiotic resistance genes.

Quorum sensing: Through quorum sensing mechanisms, P. gingivalis can coordinate gene expression with other bacteria, influencing collective behaviors like biofilm formation and virulence factor production.

Competition: Despite its cooperative relationships, P. gingivalis also competes with certain bacteria for resources and space within the oral microbiome.

Modulation of host responses: The immunomodulatory effects of P. gingivalis can create an environment that benefits not only itself but also other pathogenic bacteria by suppressing host defenses.

These interactions highlight the ecological complexity of periodontal disease, where P. gingivalis functions not in isolation but as part of a dysbiotic microbial community that collectively drives disease progression.

Research Significance

P. gingivalis has been the subject of extensive research due to its significant role in periodontal disease and potential implications in systemic health:

Model organism: P. gingivalis serves as a model organism for studying host-pathogen interactions, bacterial virulence mechanisms, and the role of the microbiome in health and disease.

**Periodo (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)