Shigella dysenteriae

Key Characteristics

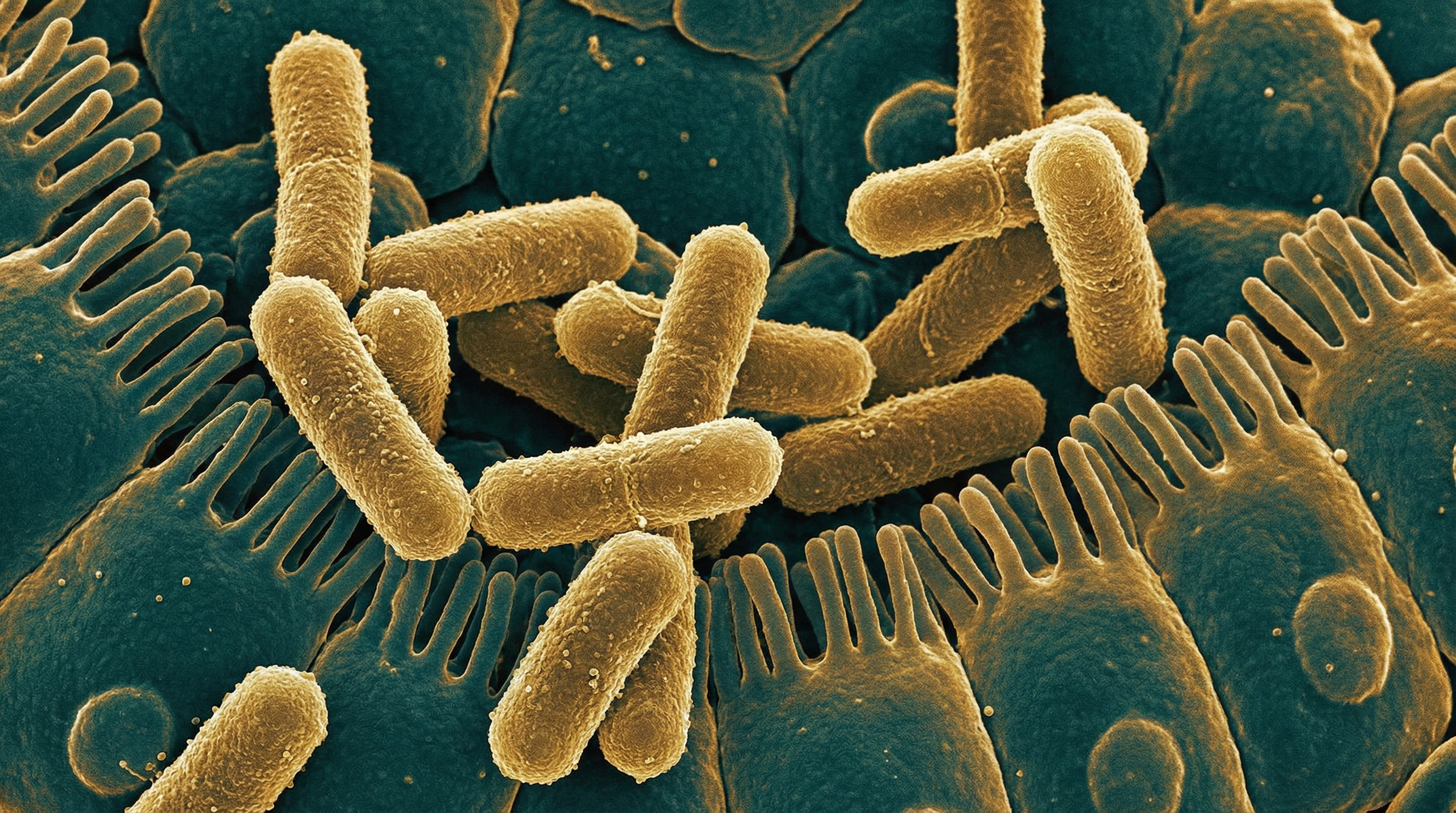

Shigella dysenteriae is a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, non-motile, non-spore-forming rod-shaped bacterium that belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae. It is the most virulent species of the genus Shigella and is the causative agent of bacillary dysentery, a severe form of bloody diarrhea. Key characteristics of S. dysenteriae include:

- Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium measuring approximately 0.5-1.0 μm in width and 2-3 μm in length

- Non-motile due to the absence of flagella

- Facultatively anaerobic, capable of both aerobic respiration and fermentation

- Non-lactose fermenting, which distinguishes it from Escherichia coli on selective media

- Catalase-positive and oxidase-negative

- Unable to produce hydrogen sulfide or utilize citrate

- Does not decarboxylate lysine, a biochemical characteristic that helps differentiate it from other Enterobacteriaceae

- Possesses a large virulence plasmid (approximately 220 kb) that encodes essential virulence factors

- Divided into 15 serotypes based on O-antigen structure, with serotype 1 being the most clinically significant

- Produces Shiga toxin (Stx), a potent cytotoxin that inhibits protein synthesis in host cells

- Contains a type III secretion system (T3SS) that injects effector proteins directly into host cells

- Capable of intracellular survival and replication within epithelial cells

- Relatively acid-resistant, allowing passage through the stomach to reach the intestine

- Highly infectious, with as few as 10-100 organisms capable of causing disease

- Genetically closely related to Escherichia coli, with approximately 80% DNA homology

- Lacks the ability to synthesize certain essential nutrients, reflecting its adaptation to the host environment

- Possesses multiple antibiotic resistance mechanisms, including plasmid-encoded resistance genes

- Optimal growth temperature of 37°C, reflecting adaptation to the human host

- Forms small, smooth, circular colonies on laboratory media

S. dysenteriae is distinguished from other Shigella species (S. flexneri, S. sonnei, and S. boydii) by its ability to produce Shiga toxin and its association with the most severe form of bacillary dysentery. Serotype 1 (S. dysenteriae type 1) is particularly important as it has been responsible for large epidemics of dysentery with high mortality rates, especially in resource-limited settings.

Role in Human Microbiome

Shigella dysenteriae is not considered a normal component of the human microbiome but rather an invasive pathogen that disrupts the established microbial community in the intestinal tract. Its relationship with the human microbiome can be characterized as follows:

Pathogenic relationship with the host:

- S. dysenteriae is an obligate human pathogen with no known environmental or animal reservoir

- It is not part of the normal commensal flora and is always considered a potential pathogen when detected

- Presence in the intestinal tract indicates infection rather than colonization

- Transmission occurs via the fecal-oral route through contaminated food, water, or direct person-to-person contact

- Unlike commensal bacteria, S. dysenteriae has evolved specifically to invade and damage the intestinal epithelium

Interactions with the gut microbiota:

- S. dysenteriae must compete with the established gut microbiota to cause infection

- The normal gut microbiota provides colonization resistance against Shigella through various mechanisms:

- Competition for nutrients and attachment sites

- Production of inhibitory compounds such as bacteriocins and short-chain fatty acids

- Stimulation of host immune responses that help control pathogens

- Disruption of the normal microbiota (e.g., through antibiotic use) may increase susceptibility to Shigella infection

- During acute infection, S. dysenteriae can significantly alter the composition of the gut microbiota:

- Reduction in beneficial bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus species

- Increase in Enterobacteriaceae and other potentially harmful bacteria

- Overall decrease in microbial diversity

Metabolic interactions:

- S. dysenteriae competes with commensal bacteria for available nutrients in the intestinal lumen

- It can reroute host cell central metabolism to obtain high-flux nutrient supply for its intracellular growth

- The inflammatory response triggered by S. dysenteriae creates a modified nutritional environment that may favor its growth over commensal bacteria

- Butyrate, a metabolite produced by certain commensal bacteria, can inhibit Shigella virulence gene expression

- The diarrhea caused by S. dysenteriae infection may flush away much of the normal microbiota, reducing competitive pressure

Microbiome recovery after infection:

- Following resolution of S. dysenteriae infection, the gut microbiota gradually returns to its pre-infection state

- Recovery time varies depending on factors such as infection severity, antibiotic treatment, and host factors

- Some alterations in microbiota composition may persist for weeks to months after clinical recovery

- Probiotics containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species have been studied as potential adjuncts to help restore normal microbiota after Shigella infection

Potential protective interactions:

- Certain commensal bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus species, may inhibit S. dysenteriae pathogenesis by:

- Competing for attachment sites on intestinal epithelial cells

- Producing antimicrobial compounds that inhibit Shigella growth

- Strengthening intestinal barrier function

- Modulating host immune responses

- These protective interactions form the basis for potential probiotic interventions against shigellosis

- Certain commensal bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus species, may inhibit S. dysenteriae pathogenesis by:

Unlike many other bacteria discussed in this collection, S. dysenteriae is not considered part of the normal human microbiome at any body site or under any circumstances. Its presence always represents a pathological state rather than a commensal relationship. The interaction between S. dysenteriae and the human microbiome is primarily characterized by competition, disruption, and the host's attempt to restore normal microbial balance following infection.

Health Implications

Shigella dysenteriae has significant negative health implications as one of the most virulent enteric pathogens affecting humans. The health impact of S. dysenteriae infection can be characterized as follows:

Bacillary dysentery (shigellosis):

- S. dysenteriae type 1 causes the most severe form of bacillary dysentery

- Clinical manifestations typically begin 1-3 days after exposure and include:

- Initial watery diarrhea that progresses to bloody, mucoid stools

- Severe abdominal cramping and tenesmus (painful, ineffective straining)

- High fever (often exceeding 39°C/102.2°F)

- Malaise, fatigue, and anorexia

- Vomiting in some cases

- Symptoms result from bacterial invasion of the colonic epithelium and the ensuing inflammatory response

- Untreated cases typically last 7-10 days, but can persist longer in vulnerable populations

- Disease severity ranges from mild to life-threatening, with S. dysenteriae type 1 associated with the highest mortality rates

Systemic complications:

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS): A potentially life-threatening condition characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury

- Primarily associated with S. dysenteriae type 1 due to Shiga toxin production

- Occurs in approximately 13% of cases, particularly in children

- Can lead to permanent kidney damage or death

- Bacteremia: Uncommon but serious complication when bacteria enter the bloodstream

- More likely in malnourished children and immunocompromised individuals

- Can lead to septic shock and multi-organ failure

- Seizures and encephalopathy: Neurological complications associated with Shiga toxin

- More common in children

- May result from direct toxin effects or metabolic disturbances

- Toxic megacolon: Severe dilatation of the colon with risk of perforation

- Rare but potentially fatal complication

- Requires urgent surgical intervention

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS): A potentially life-threatening condition characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury

Vulnerable populations:

- Children under 5 years: Experience higher incidence and severity of disease

- Particularly vulnerable to dehydration and systemic complications

- Higher case fatality rates, especially in resource-limited settings

- Elderly individuals: Increased risk of severe disease and complications

- Age-related changes in gut immunity and comorbidities contribute to vulnerability

- Malnourished individuals: More susceptible to infection and complications

- Impaired immune function increases risk of severe disease

- Infection further exacerbates malnutrition, creating a vicious cycle

- Immunocompromised patients: Higher risk of prolonged and severe disease

- Includes individuals with HIV/AIDS, those on immunosuppressive therapy, and transplant recipients

- Increased risk of bacteremia and other systemic complications

- Children under 5 years: Experience higher incidence and severity of disease

Long-term consequences:

- Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: Persistent altered bowel habits and abdominal pain

- Occurs in approximately 10-15% of patients following shigellosis

- May persist for months to years after the acute infection

- Malnutrition: Particularly significant in children in endemic areas

- Repeated episodes can lead to growth stunting and developmental delays

- Reactive arthritis: Sterile inflammatory arthritis following infection

- More common in individuals with HLA-B27 genetic marker

- Typically affects large joints and may become chronic in some cases

- Cognitive impairment: Emerging evidence suggests potential neurodevelopmental effects in children

- May result from systemic inflammation, malnutrition, or direct toxin effects

- Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: Persistent altered bowel habits and abdominal pain

Public health impact:

- Epidemic potential: S. dysenteriae type 1 has caused large-scale epidemics with high mortality rates

- Particularly in settings of war, natural disasters, and refugee crises

- Rapid person-to-person spread in crowded conditions with poor sanitation

- Antimicrobial resistance: Increasing resistance to multiple antibiotics

- Limits treatment options and increases disease severity

- Contributes to higher healthcare costs and mortality

- Economic burden: Substantial costs related to healthcare, lost productivity, and prevention

- Disproportionately affects resource-limited countries

- Contributes to perpetuation of poverty in endemic areas

- Epidemic potential: S. dysenteriae type 1 has caused large-scale epidemics with high mortality rates

Prevention challenges:

- No licensed vaccine: Despite decades of research, no effective vaccine is currently available

- Low infectious dose: As few as 10-100 organisms can cause disease, making prevention challenging

- Environmental persistence: Can survive in food and water for days to weeks

- Multiple transmission routes: Includes contaminated food, water, fomites, and direct contact

The health implications of S. dysenteriae infection are particularly severe in settings with limited access to clean water, adequate sanitation, and healthcare. The combination of high virulence, low infectious dose, and increasing antimicrobial resistance makes S. dysenteriae a significant global health concern, especially in resource-limited regions.

Metabolic Activities

Shigella dysenteriae exhibits distinctive metabolic characteristics that contribute to its pathogenicity and survival within the human host. Key aspects of S. dysenteriae metabolism include:

Central carbon metabolism:

- Utilizes both aerobic respiration and fermentation for energy generation

- Contains complete glycolytic pathway for glucose metabolism

- Lacks the ability to ferment lactose, a distinguishing characteristic from E. coli

- Possesses functional tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for aerobic energy production

- Capable of mixed acid fermentation under anaerobic conditions

- Produces acids (primarily formic, acetic, and lactic) during fermentation

- Cannot utilize citrate as a sole carbon source

- Metabolizes pyruvate through multiple pathways depending on oxygen availability

- Lacks the enzymes for gluconeogenesis from simple carbon sources

Intracellular metabolism and nutrient acquisition:

- Reroutes host cell central metabolism to obtain nutrients for rapid intracellular growth

- Captures host cell pyruvate as a primary carbon and energy source

- Utilizes a simple three-step pathway to metabolize pyruvate with acetate as an excreted waste product

- Maintains host cell ATP generation and energy charge despite vigorous exploitation

- Acquires amino acids from host cells rather than synthesizing them de novo

- Upregulates transporters for nutrient acquisition in the intracellular environment

- Adapts metabolic pathways to the nutrient-rich cytosolic environment

- Competes with host cells for essential nutrients such as iron

Iron acquisition and metabolism:

- Requires iron for various metabolic processes and virulence

- Produces siderophores (enterobactin) to scavenge iron from the host environment

- Contains iron-regulated outer membrane proteins for siderophore uptake

- Expresses systems for utilizing heme as an iron source

- Regulates iron acquisition genes through the Fur (ferric uptake regulator) system

- Competes with host cells and other microorganisms for limited available iron

- Adapts to iron-limited conditions in the intestinal environment

Nitrogen metabolism:

- Capable of utilizing various nitrogen sources including ammonia and amino acids

- Contains pathways for amino acid biosynthesis but preferentially acquires them from the host

- Lacks the ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite, unlike many other Enterobacteriaceae

- Possesses deaminases for amino acid catabolism

- Cannot decarboxylate lysine, a distinguishing biochemical characteristic

- Utilizes amino acids both as carbon and nitrogen sources during intracellular growth

Stress response metabolism:

- Adapts metabolism to survive acidic conditions during gastric passage

- Contains acid resistance systems including glutamate-, arginine-, and lysine-dependent systems

- Modifies metabolism in response to oxidative stress encountered during host immune response

- Expresses heat shock proteins and alters metabolic pat (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)