Staphylococcus hominis

Characteristics

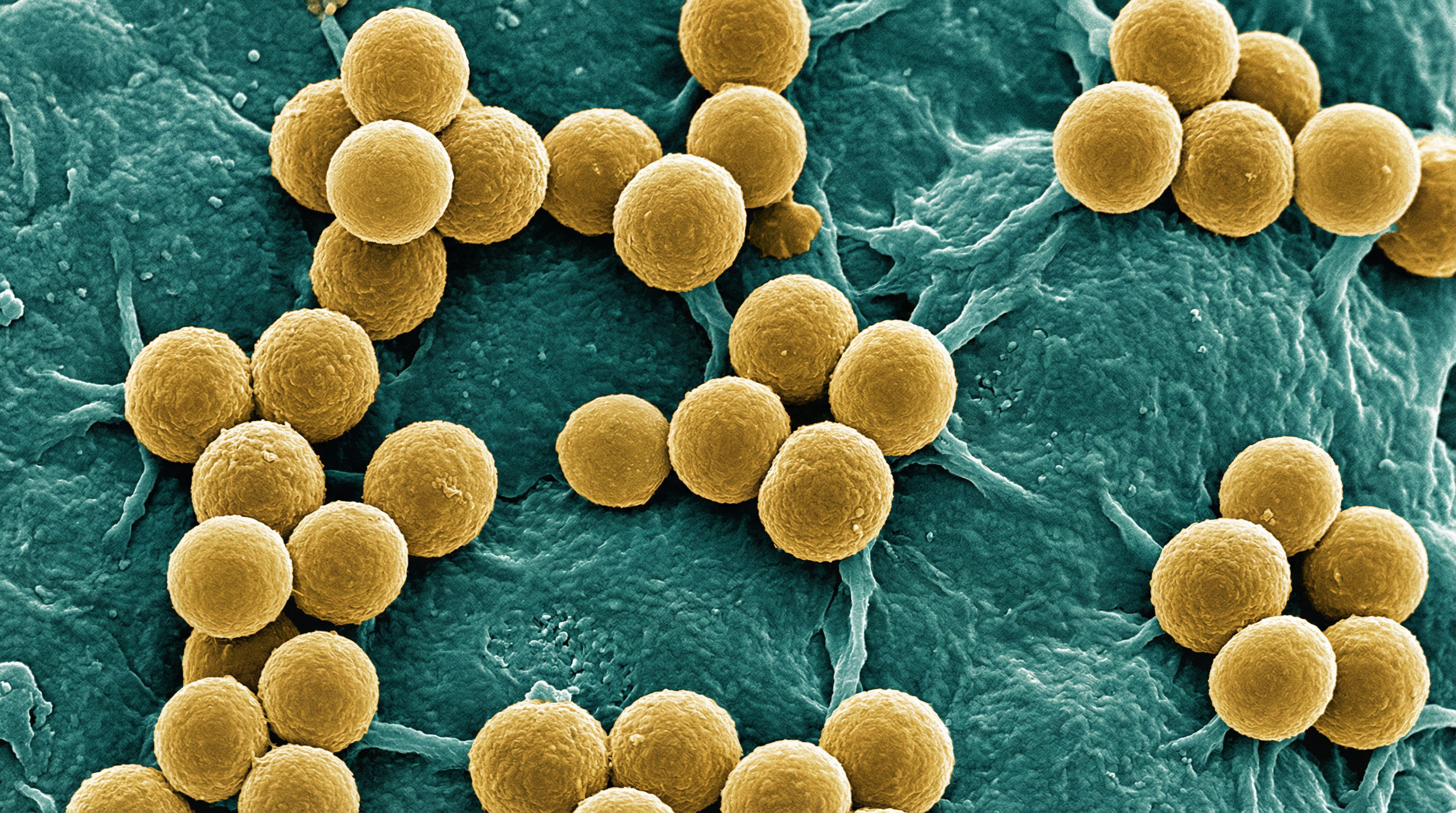

Staphylococcus hominis is a Gram-positive, coagulase-negative member of the Staphylococcaceae family that exists primarily as a commensal organism on the human skin. The name "hominis" is derived from the Latin term meaning "humans," reflecting its primary habitat on the human body. S. hominis cells are spherical cocci with a diameter of approximately 1.0-1.5 μm that typically arrange in clusters, pairs, or tetrads, characteristic of the Staphylococcus genus.

S. hominis is non-motile, non-spore-forming, and facultatively anaerobic, though it shows weak and delayed growth under anaerobic conditions. Unlike Staphylococcus aureus, S. hominis does not possess a capsule surrounding its cell wall. The cell wall is composed of peptidoglycan and teichoic acid, providing structural integrity and protection. Like other coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), S. hominis has fewer cell wall adhesins and cell wall-associated proteins compared to coagulase-positive species.

S. hominis has been divided into two subspecies:

- S. hominis subsp. hominis - susceptible to novobiocin and primarily found on the skin surface

- S. hominis subsp. novobiosepticus - resistant to novobiocin and more commonly isolated from blood

When cultured, S. hominis forms circular, cream-colored to white colonies on nutrient agar, typically 1 mm in diameter with an entire margin, raised elevation, and a dense center with transparent borders. On Mannitol Salt Agar, it forms small pink to red colonies as it cannot ferment mannitol. The optimum temperature for growth is 37°C, though some growth occurs between 20°C and 45°C. The organism can grow in the presence of up to 10% NaCl, with decreased growth at 15% concentration.

S. hominis strains are known to colonize the skin for relatively short periods (several weeks to several months) compared to other staphylococci like S. epidermidis, which can persist for one to several years. This transient colonization pattern contributes to the dynamic nature of the skin microbiome.

Role in Human Microbiome

S. hominis is the second most frequently isolated coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species from healthy human skin, accounting for approximately 22% of all staphylococci found on the skin surface. Unlike S. epidermidis, which predominantly colonizes the upper body, S. hominis is more abundant in the lower parts of the body, particularly in areas with numerous apocrine glands that retain moisture, such as the axillae (armpits), perineal region, and groin area. It is also found on the scalp of preadolescent children.

The distribution of S. hominis on the human body is not uniform, and its population density varies across different body sites. It is found in virtually all parts of the body in different numbers, with these numbers changing over time due to its tendency to colonize certain areas for shorter periods compared to other staphylococci.

S. hominis plays a protective role in the skin microbiome through several mechanisms:

Production of antimicrobial substances: Many strains of S. hominis produce bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that selectively inhibit pathogenic bacteria, particularly S. aureus.

Quorum sensing interference: S. hominis produces autoinducing peptides (AIPs) that can inhibit the accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum sensing system of S. aureus, thereby suppressing its virulence factor production.

Competitive exclusion: By occupying ecological niches on the skin, S. hominis prevents colonization by potentially harmful bacteria.

Immune modulation: S. hominis may interact with keratinocytes and other skin cells to promote barrier function and modulate local immune responses.

The presence of S. hominis in the skin microbiome during infancy has been correlated with a reduced likelihood of developing atopic dermatitis later in life, suggesting a potential protective role in skin health. Unlike S. aureus or S. epidermidis, S. hominis does not expand in atopic dermatitis lesions, further supporting its beneficial role in maintaining skin homeostasis.

Health Implications

S. hominis primarily exerts beneficial effects on human health through its protective role in the skin microbiome. However, it can also act as an opportunistic pathogen under certain circumstances.

Beneficial Effects:

Protection against pathogens: S. hominis produces antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, particularly S. aureus. These include bacteriocins like micrococcin P (MP1) and hominicin, which have potent activity against clinically relevant strains of S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

Suppression of virulence: Through the production of autoinducing peptides (AIPs), S. hominis can inhibit the accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum sensing system of S. aureus, thereby reducing the expression of virulence factors and potentially limiting skin damage during infection.

Prevention of atopic dermatitis: Colonization with S. hominis in infancy has been associated with a reduced risk of developing atopic dermatitis later in life. In clinical trials, application of lantibiotic-producing S. hominis strains has shown promise as a topical treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis.

Skin barrier maintenance: S. hominis may contribute to maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier through interactions with keratinocytes and other skin cells.

Skin aesthetics: Recent studies have suggested that S. hominis may improve skin appearance, with higher abundance associated with better skin properties. Application of S. hominis has been shown to improve conspicuous pore number, melanin index, and wrinkle count compared to placebo.

Harmful Effects (as an opportunistic pathogen):

Nosocomial infections: Like other coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. hominis can cause hospital-acquired infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients or those with implanted medical devices.

Catheter-related bloodstream infections: S. hominis is one of the coagulase-negative staphylococci commonly associated with catheter-related bloodstream infections.

Endocarditis: S. hominis has been implicated in cases of infective endocarditis, particularly involving prosthetic heart valves.

Antibiotic resistance: Some strains of S. hominis, particularly S. hominis subsp. novobiosepticus, have developed multidrug resistance, complicating treatment of infections.

The balance between beneficial and harmful effects of S. hominis depends on various factors, including the specific strain, the host's immune status, and the presence of predisposing factors such as implanted medical devices. In healthy individuals with intact immune systems, S. hominis primarily acts as a beneficial commensal, contributing to skin health and protection against pathogens.

Metabolic Activities

S. hominis exhibits metabolic versatility that allows it to thrive in the nutrient-limited environment of the human skin. As a facultative anaerobe, it can utilize both aerobic and anaerobic metabolic pathways, though it shows preference for aerobic metabolism.

Carbohydrate Metabolism:

Glycolysis: S. hominis utilizes the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway for glucose metabolism, converting glucose to pyruvate with the generation of ATP.

Fermentation: Under anaerobic conditions, S. hominis can ferment glucose to produce lactic acid as the primary end product. However, it cannot ferment mannitol, which is a distinguishing characteristic used in laboratory identification.

Pentose Phosphate Pathway: This pathway is active in S. hominis, providing NADPH for biosynthetic reactions and generating pentoses for nucleic acid synthesis.

Carbohydrate Utilization: S. hominis can utilize various carbohydrates, including glucose, fructose, and sucrose, but not mannitol or lactose.

Lipid Metabolism:

Fatty Acid Synthesis: S. hominis possesses the enzymes necessary for fatty acid biosynthesis, which are essential for membrane phospholipid formation.

Lipase Production: Some strains of S. hominis produce lipases that can hydrolyze lipids, potentially contributing to its ability to survive in the lipid-rich environment of the skin.

Protein and Amino Acid Metabolism:

Proteases: S. hominis produces various proteases that can degrade proteins, potentially contributing to nutrient acquisition and tissue invasion during opportunistic infections.

Amino Acid Utilization: S. hominis can utilize various amino acids as carbon and nitrogen sources.

Other Metabolic Activities:

Urease Activity: Some strains of S. hominis exhibit urease activity, hydrolyzing urea to ammonia and carbon dioxide.

Catalase Production: S. hominis is catalase-positive, producing the enzyme catalase that converts hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, protecting the bacterium from oxidative stress.

Coagulase and Clumping Factor: S. hominis is coagulase-negative and does not produce clumping factor, distinguishing it from S. aureus.

Bacteriocin Production: Many strains of S. hominis produce bacteriocins, which are ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides that inhibit the growth of closely related bacteria, particularly S. aureus.

Autoinducing Peptide (AIP) Production: S. hominis produces at least six different types of AIPs that can interfere with the quorum sensing systems of other staphylococci, particularly S. aureus.

The metabolic activities of S. hominis contribute to its ability to colonize the skin, compete with other microorganisms, and occasionally cause opportunistic infections. The production of antimicrobial substances and quorum sensing inhibitors is particularly important for its role in the skin microbiome, providing protection against pathogenic bacteria.

Clinical Relevance

While S. hominis is primarily a beneficial commensal organism, it has clinical relevance both as a potential therapeutic agent and as an opportunistic pathogen.

Diagnostic Considerations:

Identification: S. hominis is identified in clinical laboratories based on colony morphology, Gram staining, catalase positivity, coagulase negativity, and biochemical tests. Molecular methods such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) provide more accurate identification.

Differentiation from other CoNS: Distinguishing S. hominis from other coagulase-negative staphylococci can be challenging due to similar phenotypic characteristics. Novobiocin susceptibility testing can help differentiate S. hominis subsp. hominis (susceptible) from S. hominis subsp. novobiosepticus (resistant).

Clinical Significance: When isolated from clinical specimens, determining whether S. hominis represents true infection or contamination can be difficult. Multiple positive cultures, clinical signs of infection, and absence of other pathogens suggest true infection.

Treatment Approaches:

Antibiotic Therapy for Infections:

- First-line treatment: For susceptible strains, beta-lactam antibiotics such as oxacillin or nafcillin are typically effective.

- Alternative treatments: For methicillin-resistant strains, vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin may be used.

- Combination therapy: In severe infections, combination therapy with rifampin or gentamicin may be considered.

Biofilm Considerations: S. hominis can form biofilms on implanted medical devices, making infections difficult to treat. In such cases, device removal may be necessary in addition to antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic Resistance: S. hominis subsp. novobiosepticus often exhibits multidrug resistance, including resistance to methicillin, aminoglycosides, macrolides, and sometimes vancomycin. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is essential for guiding therapy.

Therapeutic Applications:

Probiotic Potential: Certain strains of S. hominis that produce antimicrobial substances have shown promise as topical probiotics for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and other skin conditions associated with S. aureus overgrowth.

Bacteriocin Production: The bacteriocins produced by S. hominis, such as micrococcin P (MP1) and hominicin, are being investigated as potential novel antimicrobials for treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant S. aureus.

Quorum Sensing Inhibition: The autoinducing peptides (AIPs) produced by S. hominis that inhibit the accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum sensing system of S. aureus represent a potential alternative to traditional antibiotics, targeting virulence rather than growth.

Skin Care Applications: Research suggests potential applications of S. hominis in cosmetic and dermatological products for improving skin appearance and health.

Prevention Strategies:

Infection Control: Standard infection control measures, including hand hygiene and aseptic technique during insertion and maintenance of intravascular catheters, help prevent nosocomial S. hominis infections.

Microbiome Preservation: Avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use and harsh skin cleansers may help maintain a healthy skin microbiome, including beneficial S. hominis populations.

Skin Barrier Support: Maintaining skin barrier integrity through proper hydration and avoiding irritants may support a healthy skin microbiome, including S. hominis.

The clinical relevance of S. hominis continues to evolve as research reveals more about its dual role as both a beneficial commensal and an opportunistic pathogen. Its potential therapeutic applications, particularly in addressing antibiotic resistance and skin disorders, represent an exciting area of ongoing investigation.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

S. hominis engages in complex interactions with other members of the skin microbiome, contributing to the overall ecological balance and health of the skin.

Interactions with Staphylococcus aureus:

Antimicrobial Production: Many strains of S. hominis produce bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that selectively inhibit S. aureus. These include:

- Micrococcin P (MP1), a potent antimicrobial effective against clinically relevant strains of S. aureus

- Hominicin, a bacteriocin with activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)

- Other strain-specific antimicrobial peptides

Quorum Sensing Interference: S. hominis produces at least six different autoinducing peptides (AIPs) that can inhibit the accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum sensing system of S. aureus. This interference reduces the expression of virulence factors by S. aureus, potentially limiting its pathogenicity.

Competitive Exclusion: By occupying similar ecological niches on the skin, S. hominis may physically prevent colonization by S. aureus through competition for attachment sites and nutrients.

Interactions with Staphylococcus epidermidis:

Coexistence: S. hominis and S. epidermidis often coexist on the skin, with S. epidermidis typically dominating the upper body and S. hominis more prevalent in the lower body.

Quorum Sensing Interference: The AIPs produced by S. hominis can also inhibit the agr system of S. epidermidis, potentially modulating its behavior within the skin microbiome.

Complementary Roles: S. hominis and S. epidermidis may play complementary roles in skin protection, wit (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)