Streptococcus mutans

Characteristics

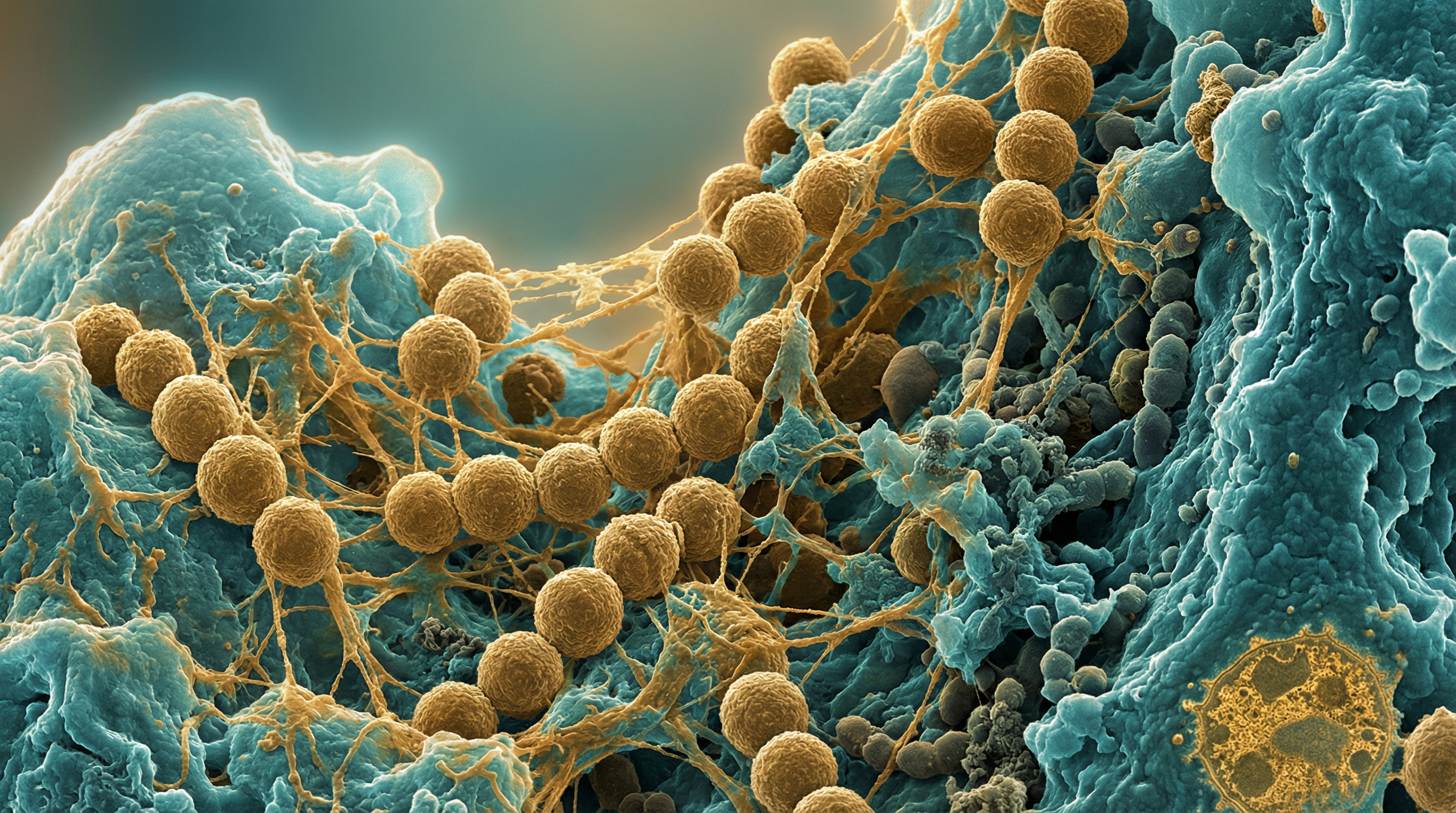

Streptococcus mutans is a Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic, non-motile, coccus-shaped bacterium that typically grows in chains. It is a member of the viridans group of streptococci and is considered the primary etiological agent of dental caries (tooth decay). S. mutans can be classified into four serological groups (c, e, f, and k) based on the composition of cell-surface rhamnose-glucose polysaccharide, with approximately 75% of strains isolated from dental plaque belonging to serotype c.

The genome of S. mutans strain UA159 (serotype c) contains approximately 2.0 Mb of DNA and encodes about 2,000 genes. The S. mutans pan-genome contains a minimum of approximately 3,300 possible genes with a core genome of 1,490 genes common to all strains. This genetic diversity contributes to variations in virulence potential and fitness among different strains.

S. mutans possesses several key virulence factors that contribute to its cariogenicity:

- Glucosyltransferases (GTFs) that synthesize extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) from sucrose

- Fructosyltransferase (FTF) that produces fructans from sucrose

- Acid production (acidogenicity) from carbohydrate metabolism

- Acid tolerance (aciduricity) allowing survival in low pH environments

- Adhesins that facilitate attachment to tooth surfaces and other bacteria

Role in Human Microbiome

S. mutans primarily resides in the human oral cavity, specifically in dental plaque, which is a multispecies biofilm formed on the hard surfaces of teeth. It is not typically part of the normal oral microbiota in pre-dentate infants but is acquired during early childhood, usually through vertical transmission from caregivers. Once established, S. mutans can persist as a member of the oral microbiome throughout life.

Within the oral microbiome, S. mutans interacts with numerous other bacterial species in complex ecological relationships. It competes with commensal streptococci like Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii for colonization sites. S. mutans can also form antagonistic relationships with certain beneficial bacteria, such as Streptococcus salivarius, which produces substances that inhibit S. mutans biofilm formation.

The ecological plaque hypothesis suggests that caries development occurs when environmental factors (like frequent sugar consumption) shift the balance of the oral microbiome toward acidogenic and aciduric species like S. mutans, leading to demineralization of tooth enamel and eventually dental caries.

Health Implications

S. mutans is primarily associated with dental caries, one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide. The cariogenic potential of S. mutans resides in three core attributes:

- The ability to synthesize large quantities of extracellular polymers of glucan from sucrose that aid in permanent colonization of tooth surfaces and development of the extracellular polymeric matrix

- The ability to transport and metabolize a wide range of carbohydrates into organic acids (acidogenicity)

- The ability to thrive under environmental stress conditions, particularly low pH (aciduricity)

When S. mutans metabolizes dietary carbohydrates, especially sucrose, it produces acids that lower the pH of the dental plaque. If the pH drops below approximately 5.5, demineralization of tooth enamel occurs, initiating the caries process. Repeated cycles of acid production and demineralization eventually lead to cavitation.

Beyond dental caries, S. mutans has been implicated in cases of infective endocarditis, a life-threatening inflammation of heart valves. A subset of strains, particularly those expressing collagen-binding proteins (CBPs) like Cnm and Cbm, have been linked to other extraoral pathologies such as cerebral microbleeds, IgA nephropathy, and atherosclerosis. These CBP-positive strains are more frequently isolated from dental plaque of individuals with bacteremia and infective endocarditis.

Metabolic Activities

S. mutans possesses versatile metabolic capabilities that contribute to its success in the oral environment:

Carbohydrate Metabolism: S. mutans can utilize various dietary carbohydrates, including glucose, fructose, sucrose, lactose, and maltose. It possesses multiple sugar transport systems, including the phosphoenolpyruvate-phosphotransferase system (PEP-PTS), which allows efficient uptake and phosphorylation of sugars.

Glycolysis and Acid Production: S. mutans primarily uses the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway for glycolysis, converting sugars to pyruvate and generating ATP. Under anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is further metabolized to various organic acids, primarily lactic acid, but also formic, acetic, and propionic acids, contributing to the acidification of the local environment.

Extracellular Polysaccharide Synthesis: S. mutans produces three types of glucosyltransferases (GTF-B, GTF-C, and GTF-D) that synthesize different types of glucans from sucrose:

- Water-insoluble glucans (α-1,3 linkages) produced by GTF-B and GTF-C

- Water-soluble glucans (α-1,6 linkages) produced by GTF-D These glucans contribute to biofilm matrix formation and bacterial adhesion.

Fructan Metabolism: S. mutans produces fructosyltransferase (FTF) that synthesizes fructans from sucrose, and exo-β-D-fructosidase (FruA) that can degrade these polymers. These enzymes allow S. mutans to store carbohydrates as extracellular polysaccharides and later utilize them when dietary sugars are limited.

Stress Responses: S. mutans has developed sophisticated mechanisms to survive acidic conditions, including:

- F-ATPase activity that pumps protons out of the cell

- Alteration of membrane fatty acid composition

- Increased production of stress proteins

- DNA repair mechanisms

These metabolic adaptations allow S. mutans to outcompete other oral bacteria in acidic environments and contribute to its cariogenic potential.

Clinical Relevance

Diagnosis

Dental caries is primarily diagnosed through clinical examination, radiographic assessment, and sometimes microbiological testing. Specific detection of S. mutans can be performed using:

- Selective culture media (e.g., Mitis Salivarius Bacitracin agar)

- Immunological methods (e.g., monoclonal antibodies)

- Molecular techniques (e.g., PCR, DNA probes)

- Chair-side tests that detect S. mutans levels in saliva

High levels of S. mutans in saliva (>10^6 CFU/ml) are associated with increased caries risk, though the relationship is not always straightforward due to the multifactorial nature of dental caries.

Treatment Approaches

Treatment strategies targeting S. mutans include:

Mechanical Removal: Regular brushing, flossing, and professional dental cleaning to disrupt biofilms.

Antimicrobial Agents:

- Chlorhexidine: A broad-spectrum antimicrobial that reduces S. mutans levels

- Essential oils: Components in some mouthwashes with antimicrobial properties

- Fluoride: Inhibits bacterial metabolism and enhances tooth remineralization

Dietary Modifications:

- Reducing frequency of fermentable carbohydrate consumption

- Using sugar substitutes (e.g., xylitol) that S. mutans cannot metabolize

Probiotics and Replacement Therapy:

- Beneficial bacteria like Streptococcus salivarius K12 and M18 that can inhibit S. mutans

- Genetically modified S. mutans strains that do not produce acids

Novel Approaches:

- Targeted antimicrobials using specific peptides

- Inhibitors of glucosyltransferases to prevent biofilm formation

- Quorum sensing inhibitors to disrupt bacterial communication

- Vaccines targeting S. mutans antigens (experimental)

Prevention Strategies

Prevention of S. mutans-associated dental caries focuses on:

- Oral hygiene practices to reduce biofilm accumulation

- Fluoride application to strengthen tooth enamel and inhibit bacterial metabolism

- Dietary counseling to reduce frequency of sugar consumption

- Dental sealants to protect susceptible tooth surfaces

- Regular dental check-ups for early detection and intervention

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

S. mutans engages in complex interactions with other members of the oral microbiome:

Competition with Commensal Streptococci:

- S. mutans competes with Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii for colonization sites

- These commensals produce hydrogen peroxide that inhibits S. mutans growth

- S. mutans produces bacteriocins (mutacins) that inhibit the growth of competing streptococci

Antagonistic Relationships:

- Streptococcus salivarius produces fructosyltransferase (FTF) and exo-β-D-fructosidase (FruA) that can inhibit S. mutans biofilm formation by interfering with sucrose metabolism

- Lactobacillus species can produce bacteriocins and organic acids that affect S. mutans growth

Synergistic Relationships:

- S. mutans can form mixed-species biofilms with Candida albicans, enhancing colonization and virulence

- Actinomyces species may facilitate S. mutans attachment to tooth surfaces

Quorum Sensing:

- S. mutans uses a competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) system for cell-to-cell communication

- This system regulates biofilm formation, genetic competence, and bacteriocin production

- Other oral bacteria can interfere with this signaling system

These microbial interactions influence the composition and cariogenic potential of dental plaque, with ecological shifts potentially leading to dysbiosis and disease.

Research Significance

S. mutans serves as an important model organism for studying:

Biofilm Formation and Development:

- Mechanisms of bacterial adhesion and aggregation

- Extracellular matrix production and composition

- Spatial organization and metabolic cooperation in multispecies biofilms

Bacterial Adaptation to Environmental Stress:

- Acid tolerance mechanisms

- Responses to oxidative stress

- Nutrient limitation adaptations

Carbohydrate Metabolism:

- Sugar transport systems

- Glycolytic pathways

- Extracellular polysaccharide synthesis

Bacterial Pathogenesis:

- Virulence factor regulation

- Host-pathogen interactions

- Polymicrobial disease development

Preventive and Therapeutic Strategies:

- Novel antimicrobial compounds

- Anti-biofilm agents

- Vaccine development

- Probiotic approaches

Research on S. mutans has broader implications beyond dental caries, including insights into biofilm-related infections, bacterial stress responses, and microbial ecology. The study of S. mutans has challenged long-standing dogmas based on bacterial paradigms such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, particularly in areas of carbohydrate metabolism, biofilm formation, and stress responses.

Recent advances in genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have led to a better understanding of the physiology and diversity of S. mutans as a species, revealing significant strain-to-strain variations in virulence potential and fitness. This heterogeneity helps explain why attempts to correlate the carriage of certain genotypes of S. mutans with the incidence of dental caries has proven difficult.

References

Lemos JA, Palmer SR, Zeng L, et al. The Biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(1):GPP3-0051-2018.

Forssten SD, Björklund M, Ouwehand AC. Streptococcus mutans, Caries and Simulation Models. Nutrients. 2010;2(3):290-298.

Ogawa A, Furukawa S, Fujita S, et al. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans Biofilm Formation by Streptococcus salivarius FruA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(5):1572-1580.

Cornejo OE, Lefébure T, Bitar PD, et al. Evolutionary and population genomics of the cavity causing bacteria Streptococcus mutans. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):881-893.

Palmer SR, Miller JH, Abranches J, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of genomically-diverse isolates of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61358.

Bowen WH, Koo H. Biology of Streptococcus mutans-derived glucosyltransferases: role in extracellular matrix formation of cariogenic biofilms. Caries Res. 2011;45(1):69-86.

Krzyściak W, Jurczak A, Kościelniak D, Bystrowska B, Skalniak A. The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(4):499-515.

Matsumoto-Nakano M. Role of Streptococcus mutans surface proteins for biofilm formation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54(1):22-29.