Streptococcus oralis

Streptococcus oralis is a gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic coccus that is a common member of the human oral microbiome. As part of the viridans group streptococci (VGS) and specifically the mitis group, S. oralis primarily colonizes the oral cavity where it typically functions as a commensal organism. However, like other oral streptococci, it can act as an opportunistic pathogen in certain circumstances, particularly when it gains access to normally sterile sites in the body.

Key Characteristics

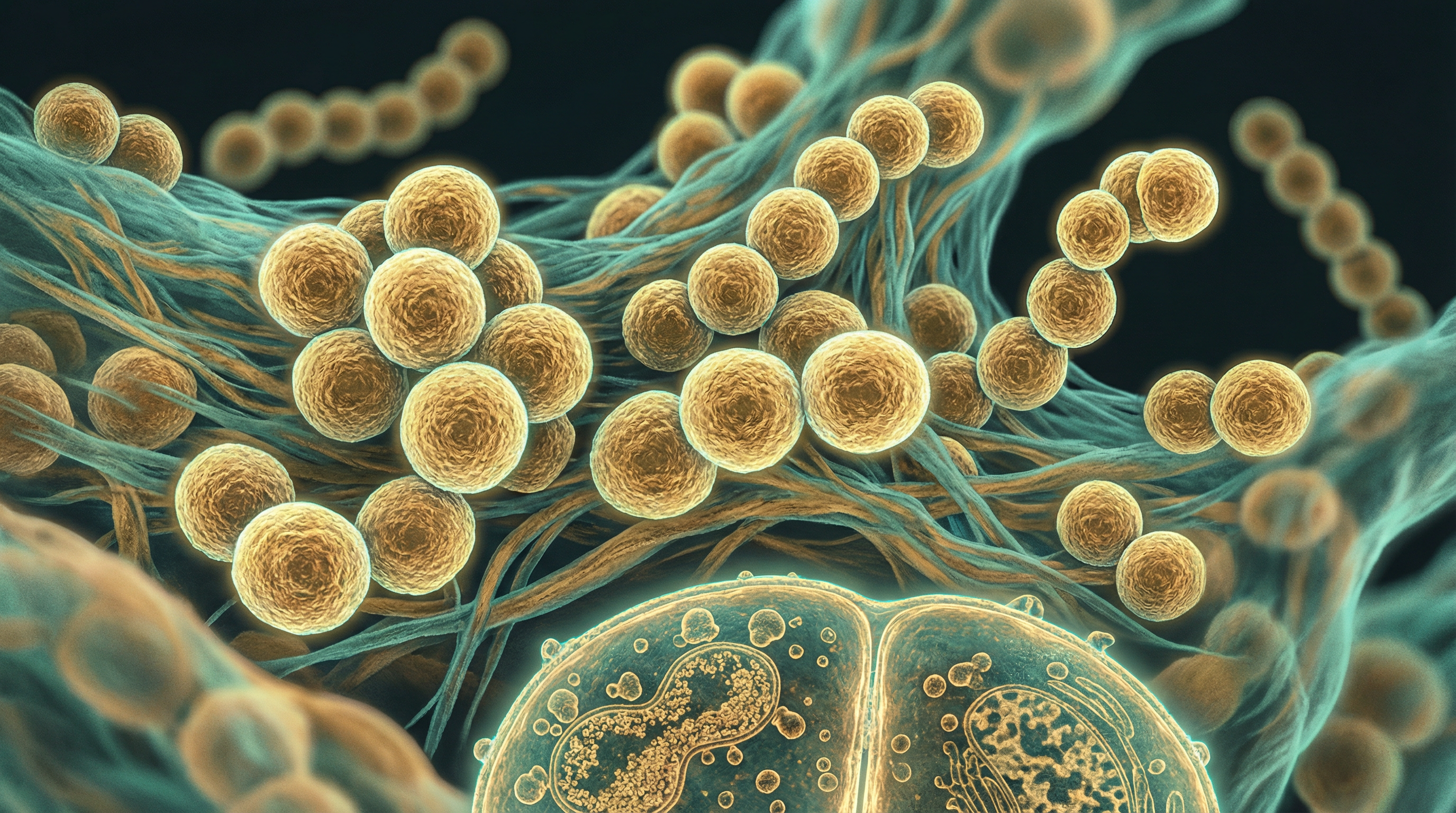

S. oralis belongs to the mitis group of streptococci, which includes closely related species such as S. mitis, S. pneumoniae, and S. infantis. It appears as chains of cocci under microscopic examination and forms alpha-hemolytic colonies on blood agar. The bacterium is non-motile, catalase-negative, and optochin-resistant.

S. oralis can be distinguished from other mitis group streptococci by its ability to ferment certain carbohydrates and its production of specific enzymes. It typically ferments mannitol, sorbitol, and inulin, and produces neuraminidase, β-galactosidase, and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. However, biochemical differentiation within the mitis group can be challenging due to phenotypic similarities and strain variations.

The bacterium possesses various surface proteins and adhesins that facilitate attachment to oral surfaces and interactions with salivary components. Particularly notable is its ability to bind salivary amylase through multiple mechanisms, which contributes to its successful colonization of the oral cavity.

Genomic analysis has revealed significant genetic diversity within S. oralis, with several subspecies now recognized: subsp. oralis, subsp. tigurinus, and subsp. dentisani. These subspecies show differences in their genetic makeup, ecological niches, and potential health impacts.

Role in Human Microbiome

S. oralis is one of the early colonizers of the oral cavity and is found in various oral sites, including:

- Dental plaque

- Saliva

- Tongue

- Buccal mucosa

- Gingival crevices

As an early colonizer, S. oralis plays a crucial role in the development and maturation of dental biofilms. It adheres to the salivary pellicle on tooth surfaces and provides attachment sites for later colonizers through coaggregation. This pioneer role in biofilm formation makes S. oralis an important determinant of the overall composition and structure of the oral microbiome.

S. oralis is detectable in the oral cavity shortly after birth and remains a stable component of the oral microbiome throughout life. Its abundance and distribution may vary with age, oral health status, and environmental factors such as diet and oral hygiene practices.

Recent research has also detected S. oralis in the intestinal microbiome, suggesting that oral bacteria can colonize distal sites in the gastrointestinal tract and potentially influence health beyond the oral cavity.

Health Implications

Commensal Role

As a commensal organism, S. oralis contributes to oral health through several mechanisms:

Biofilm ecology: By occupying niches in the oral biofilm, S. oralis can help maintain a balanced microbial community that resists colonization by more pathogenic species.

pH modulation: Some strains of S. oralis subsp. dentisani produce ammonia from arginine, which can help neutralize acidic conditions in the oral cavity and potentially protect against dental caries.

Immune education: As a common commensal, S. oralis may play a role in the development and regulation of local immune responses in the oral mucosa.

Bacteriocin production: Some strains produce bacteriocins that can inhibit the growth of competing bacteria, potentially including pathogens.

Pathogenic Potential

Despite its predominant role as a commensal, S. oralis can act as an opportunistic pathogen under certain conditions:

Infective endocarditis: S. oralis is among the viridans streptococci that can cause infective endocarditis, particularly in individuals with pre-existing heart valve abnormalities.

Bacteremia: In immunocompromised patients, especially those with cancer and neutropenia, S. oralis can cause bacteremia that may range from asymptomatic to severe.

Respiratory infections: S. oralis has been implicated in aspiration pneumonia and other respiratory infections, particularly in hospitalized or immunocompromised patients.

Dental caries: While less acidogenic than S. mutans, S. oralis can contribute to dental caries, especially in the early stages of lesion development.

Urinary tract infections: Recent research suggests that intestinal colonization with S. oralis may contribute to urinary tract infections through immune modulation and interactions with uropathogenic bacteria.

The transition from commensal to pathogen typically occurs when S. oralis gains access to normally sterile sites through tissue damage, invasive procedures, or immune compromise.

Metabolic Activities

S. oralis exhibits various metabolic capabilities that enable it to thrive in the oral environment:

Carbohydrate metabolism: It can ferment various sugars, including glucose, sucrose, maltose, and lactose, producing primarily lactic acid as an end product.

Amylase binding: S. oralis can bind salivary amylase, which may provide nutritional advantages by localizing the enzyme that breaks down dietary starch into maltose and maltodextrins.

Neuraminidase production: It produces neuraminidase enzymes that cleave sialic acid residues from host glycoproteins, potentially facilitating adhesion and nutrient acquisition.

Arginine metabolism: Some strains, particularly S. oralis subsp. dentisani, can metabolize arginine via the arginine deiminase system, producing ammonia that can neutralize acids.

Extracellular polysaccharide synthesis: It can produce extracellular polysaccharides that contribute to biofilm formation and adhesion to oral surfaces.

These metabolic activities allow S. oralis to adapt to the dynamic conditions of the oral environment and contribute to its ecological success as a commensal organism.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical significance of S. oralis primarily relates to its role as an opportunistic pathogen:

Infective endocarditis: S. oralis is a significant cause of viridans streptococcal endocarditis, which typically has a subacute presentation. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be recommended for high-risk patients undergoing dental procedures.

Bacteremia in immunocompromised patients: S. oralis bacteremia in neutropenic cancer patients can cause significant morbidity and may contribute to the viridans streptococcal shock syndrome.

Antibiotic resistance: Increasing resistance to beta-lactams, macrolides, and other antibiotics has been observed in S. oralis isolates, complicating treatment of infections.

Diagnostic challenges: Accurate identification of S. oralis in clinical specimens can be challenging due to its phenotypic similarities to other viridans streptococci, particularly S. mitis.

Probiotic potential: Some strains, particularly S. oralis subsp. dentisani, are being investigated for their potential probiotic applications in preventing dental caries due to their arginine deiminase activity.

Understanding the factors that determine whether S. oralis acts as a commensal or pathogen in different host contexts remains an important area of clinical research.

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

S. oralis engages in complex interactions with other members of the oral microbiome:

Coaggregation: It can coaggregate with various oral bacteria, including Actinomyces species, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and other streptococci, contributing to biofilm formation and structure.

Interspecies communication: S. oralis participates in quorum sensing and may influence the behavior of other bacteria through signaling molecules.

Synergistic relationships: In dental plaque, S. oralis can form synergistic relationships with other early colonizers, creating a favorable environment for later colonizers.

Antagonistic relationships: Through competition for nutrients and production of bacteriocins, S. oralis may inhibit the growth of certain competing bacteria.

Horizontal gene transfer: S. oralis can exchange genetic material with other streptococci, including virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes. This is particularly significant with closely related species like S. mitis and S. pneumoniae.

These interactions contribute to the ecological balance of the oral microbiome and can influence both health and disease states.

Research Significance

S. oralis has become an important focus of research for several reasons:

Biofilm formation: As an early colonizer, S. oralis provides insights into the initial stages of dental biofilm formation and development.

Taxonomic complexity: The genetic diversity within S. oralis and its close relationship to other mitis group streptococci make it an interesting model for studying bacterial taxonomy and evolution.

Commensal-pathogen transition: Understanding the factors that determine whether S. oralis acts as a commensal or pathogen may reveal general principles about opportunistic infections.

Antibiotic resistance: S. oralis can serve as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes that may be transferred to more pathogenic species.

Probiotic applications: The potential caries-protective effects of certain S. oralis strains, particularly subsp. dentisani, are being investigated for oral health applications.

Oral-systemic connections: The presence of S. oralis in the intestinal microbiome and its potential influence on distant sites like the urinary tract highlight the importance of understanding the broader health impacts of oral bacteria.

Continued research on S. oralis promises to enhance our understanding of both oral and systemic health and may lead to novel therapeutic approaches.

References

Do T, Jolley KA, Maiden MC, et al. Population structure of Streptococcus oralis. Microbiology (Reading). 2009;155(Pt 8):2593-2602.

Palmer RJ Jr. Composition and development of oral bacterial communities. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64(1):20-39.

Shelburne SA, Sahasrabhojane P, Saldana M, et al. Streptococcus mitis strains causing severe clinical disease in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(5):762-771.

Rasmussen LH, Højholt K, Dargis R, et al. In silico assessment of virulence factors in strains of Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus mitis isolated from patients with Infective Endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(9):1316-1323.

Conrads G, Westenberger J, Lürkens M, Abdelbary MMH. Isolation and bacteriocin-related typing of Streptococcus dentisani. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:110.

Velsko IM, Chakraborty B, Nascimento MM, et al. Species designations belie phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity in oral streptococci. mSystems. 2018;3(6):e00158-18.