Streptococcus pyogenes

Characteristics

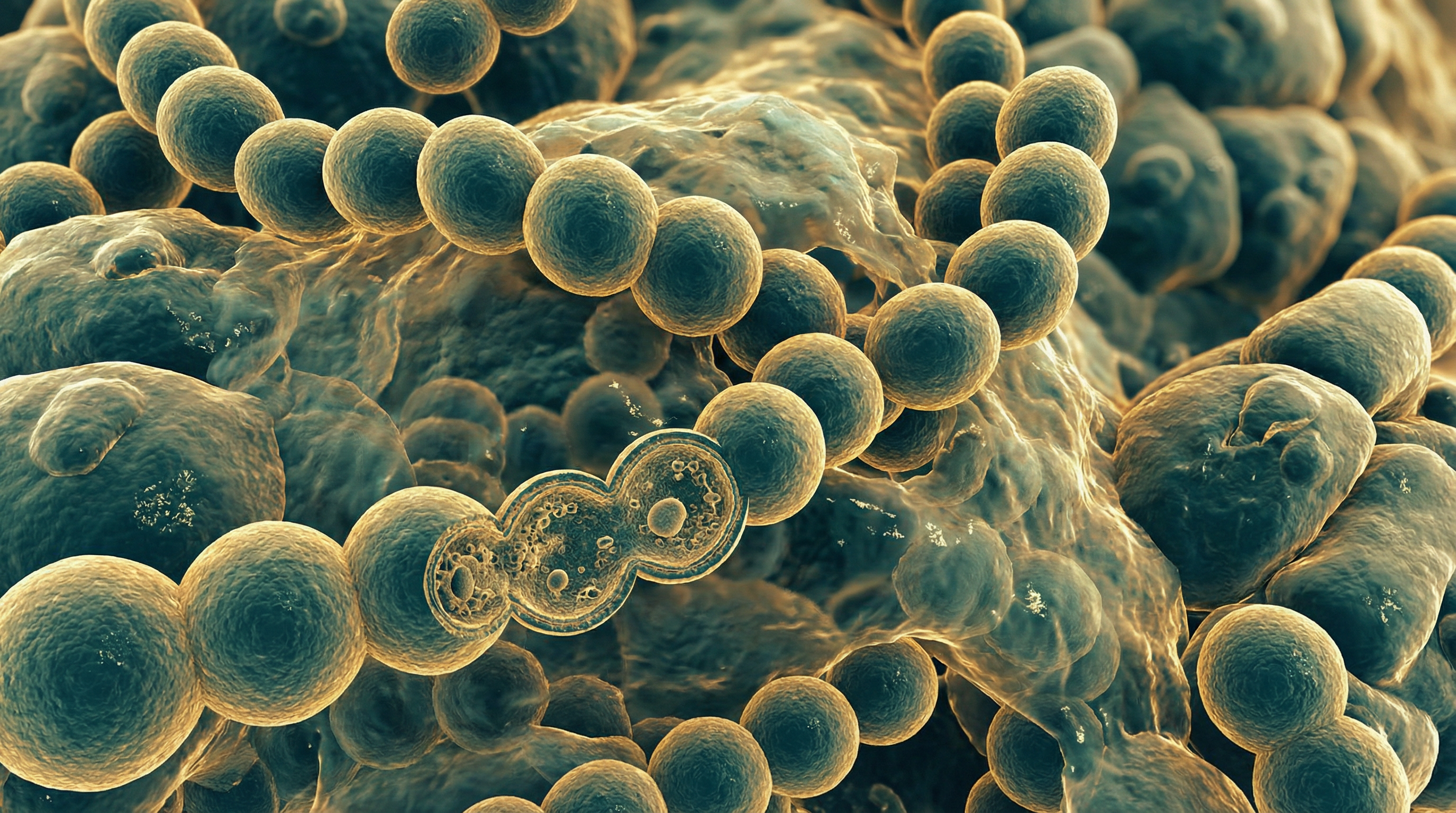

Streptococcus pyogenes, commonly known as Group A Streptococcus (GAS), is a Gram-positive, catalase-negative, oxidase-negative, β-hemolytic, non-motile, non-spore-forming coccus that typically grows in chains or pairs. It is a facultative anaerobe that grows best in 5-10% carbon dioxide environments. When cultured on blood agar plates, S. pyogenes produces small (2-3 mm) colonies surrounded by zones of complete (β) hemolysis, which is the destruction of red blood cells.

S. pyogenes is classified as a Group A Streptococcus according to the Lancefield serological grouping system, based on the carbohydrate composition of its cell wall. The type A antigen is a polysaccharide comprised of N-acetylglucosamine attached to a rhamnose polymer backbone. The bacterium possesses an M protein, a major surface protein that extends from the cell membrane through the cell wall, which serves as the basis for further serotyping. More than 80 different M protein serotypes have been identified, contributing to the diversity of S. pyogenes strains and their varying virulence potential.

S. pyogenes possesses numerous virulence factors that contribute to its pathogenicity:

- M protein - inhibits phagocytosis and promotes adhesion

- Hyaluronic acid capsule - antiphagocytic and aids in tissue adherence

- Streptolysins O and S - cytolytic toxins that damage cell membranes

- Pyrogenic exotoxins (SPEs) - superantigens that trigger massive T-cell activation

- Streptokinase - activates plasminogen to dissolve blood clots

- DNases - degrade neutrophil extracellular traps

- Hyaluronidase - degrades hyaluronic acid in connective tissues

- C5a peptidase - cleaves complement component C5a

- Streptococcal inhibitor of complement (SIC) - interferes with complement function

Role in Human Microbiome

S. pyogenes is not typically considered a commensal organism or a normal part of the human microbiome. Instead, it is primarily a human-specific pathogen that transiently colonizes the throat, skin, and respiratory tract. The primary ecological niches for S. pyogenes include the pharynx, tonsils, skin, rectum, and vagina. Asymptomatic carriage can occur, particularly in the throat, with carriage rates varying from 5-20% in healthy children and lower rates in adults.

Unlike many other streptococci that are part of the normal oral and nasopharyngeal flora, S. pyogenes is generally considered an exogenous pathogen rather than a resident microbiome member. When present, it can disrupt the normal microbiome balance and interact with other microorganisms in complex ways:

- Competition with commensal streptococci for nutrients and attachment sites

- Antagonistic relationships with some resident bacteria that produce bacteriocins

- Synergistic relationships with certain pathogens, potentially enhancing virulence

- Modulation of host immune responses that may affect the broader microbiome

The presence of S. pyogenes in the throat or on the skin is often transient, and its ability to cause disease depends on various factors including strain virulence, host susceptibility, and the composition of the local microbiome.

Health Implications

S. pyogenes is responsible for a wide spectrum of diseases ranging from mild localized infections to severe invasive and toxin-mediated conditions:

Suppurative (Pus-Forming) Infections:

- Pharyngitis (Strep Throat) - Acute inflammation of the pharynx and tonsils, characterized by sore throat, fever, and cervical lymphadenopathy. It accounts for 15-30% of cases of pharyngitis in children and 5-20% in adults.

- Impetigo - A highly contagious superficial skin infection characterized by honey-colored crusted lesions, primarily affecting children.

- Erysipelas - A superficial skin infection with well-demarcated borders, typically affecting the face or legs.

- Cellulitis - A deeper skin infection involving the subcutaneous tissues.

- Scarlet Fever - Pharyngitis accompanied by a characteristic sandpaper-like rash due to pyrogenic exotoxin production.

Invasive Infections:

- Necrotizing Fasciitis - A rapidly progressing infection of the fascia and subcutaneous tissues, often referred to as "flesh-eating disease."

- Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome (STSS) - A severe systemic illness characterized by hypotension, multi-organ failure, and a high mortality rate.

- Bacteremia - Bloodstream infection that can lead to seeding of other sites.

- Puerperal Sepsis - Infection of the uterus following childbirth.

- Pneumonia - Less common but severe form of pneumonia.

Post-Infectious Sequelae:

- Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF) - An inflammatory disease that can develop 2-3 weeks after untreated strep throat, affecting the heart, joints, skin, and brain. It can lead to rheumatic heart disease with permanent valve damage.

- Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis (PSGN) - An immune complex-mediated kidney disease that can occur following certain strains of S. pyogenes infection.

The global burden of S. pyogenes infections is substantial, with an estimated 18.1 million cases of severe disease and 1.78 million new cases annually. Approximately 616 million cases of pharyngitis and 111 million cases of skin infections occur worldwide each year. The disease causes about 500,000 deaths annually, primarily due to invasive infections, rheumatic heart disease, and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

Metabolic Activities

S. pyogenes possesses a relatively simple but efficient metabolism that enables it to thrive in various host environments:

Carbohydrate Metabolism:

- Fermentative Metabolism - S. pyogenes is a lactic acid bacterium that relies primarily on fermentative metabolism. It lacks a complete tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory chain, instead using glycolysis (Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway) to convert glucose to pyruvate.

- Homofermentative Lactic Acid Production - Under anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is converted to lactic acid by lactate dehydrogenase, regenerating NAD+ for continued glycolysis. This results in acidification of the surrounding environment.

- Mixed Acid Fermentation - Under aerobic conditions, S. pyogenes can shift to mixed acid fermentation, producing formate, acetate, and ethanol in addition to lactate.

- Carbohydrate Utilization - S. pyogenes can metabolize various sugars including glucose, fructose, maltose, and sucrose, but not lactose or mannitol. It possesses multiple carbohydrate transport systems, including phosphoenolpyruvate-phosphotransferase systems (PEP-PTS).

Amino Acid Metabolism:

- Amino Acid Auxotrophy - S. pyogenes is auxotrophic for approximately 15 amino acids, meaning it cannot synthesize them and must acquire them from the environment.

- Arginine Metabolism - The arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway allows S. pyogenes to generate ATP under acidic conditions by converting arginine to ornithine, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, which helps neutralize acidic environments.

- Glutamine Utilization - Glutamine is a critical amino acid for S. pyogenes growth and metabolism.

Other Metabolic Pathways:

- Aerobic Metabolism - Despite lacking a complete respiratory chain, S. pyogenes can consume oxygen through the activity of NADH oxidase and NADH peroxidase, which helps regenerate NAD+ for continued glycolysis.

- Salvage NAD Biosynthesis - S. pyogenes lacks the de novo pathway for NAD synthesis and relies on salvage pathways to recycle nicotinamide and nicotinic acid.

- Nucleotide Biosynthesis - S. pyogenes possesses both de novo and salvage pathways for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis.

- Metal Ion Transport - S. pyogenes has sophisticated systems for the acquisition and transport of essential metal ions including iron, manganese, zinc, and copper.

- F-ATPase Activity - The F-ATPase functions primarily to pump protons out of the cell, maintaining intracellular pH homeostasis rather than generating ATP.

These metabolic capabilities allow S. pyogenes to adapt to different host environments and contribute to its pathogenicity by enabling survival under various stress conditions.

Clinical Relevance

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of S. pyogenes infections involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing:

Throat Culture - The gold standard for diagnosing streptococcal pharyngitis, with high sensitivity (90-95%) but requiring 24-48 hours for results.

Rapid Antigen Detection Tests (RADT) - Provide results within minutes with high specificity (95%) but variable sensitivity (70-90%). Negative RADT results in children and adolescents should be confirmed with throat culture.

Molecular Methods - Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) such as PCR offer high sensitivity and specificity with faster turnaround times than culture.

Serological Tests - Anti-streptolysin O (ASO) and anti-DNase B antibody tests are useful for diagnosing post-streptococcal sequelae like rheumatic fever but not acute infection.

Blood Culture - Essential for diagnosing invasive infections like bacteremia and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

Imaging Studies - CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound may be necessary to diagnose deep tissue infections like necrotizing fasciitis.

Treatment Approaches

Antibiotic Therapy:

- Penicillin - Remains the first-line treatment for S. pyogenes infections due to lack of resistance. Oral penicillin V for uncomplicated pharyngitis and impetigo; intramuscular benzathine penicillin G for patients with compliance concerns.

- Amoxicillin - Often preferred for children due to better taste and once-daily dosing options.

- Cephalosporins - First-generation cephalosporins are alternatives for penicillin-allergic patients (without anaphylaxis history).

- Macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin) - Used for patients with severe penicillin allergy, though resistance rates of 5-20% exist in some regions.

- Clindamycin - Often added to treatment regimens for severe invasive infections due to its ability to suppress toxin production.

- Vancomycin or Linezolid - Reserved for severe infections or treatment failures.

Supportive Care:

- Fluid and electrolyte management

- Pain control

- Antipyretics for fever

- Respiratory support when needed

Surgical Interventions:

- Debridement and fasciotomy for necrotizing fasciitis

- Drainage of abscesses

- Wound care for skin infections

Adjunctive Therapies:

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for some cases of necrotizing fasciitis

- Corticosteroids for certain presentations of severe pharyngitis

Prevention Strategies

Antibiotic Prophylaxis:

- Secondary prevention of rheumatic fever with monthly benzathine penicillin G injections or daily oral penicillin

- Prophylaxis for high-risk contacts of invasive GAS cases in certain situations

Infection Control Measures:

- Hand hygiene

- Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette

- Contact precautions for hospitalized patients with invasive disease

- Proper wound care

Vaccine Development:

- Despite decades of research, no licensed vaccine is currently available

- Vaccine candidates in development include:

- M protein-based vaccines

- Group A carbohydrate vaccines

- Conserved protein antigens vaccines

- Combination approaches

Public Health Surveillance:

- Monitoring of invasive disease trends

- Outbreak investigation and management

- Antimicrobial resistance surveillance

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

S. pyogenes engages in complex interactions with other microorganisms in the human host:

Competition with Commensal Streptococci:

- Viridans group streptococci in the oropharynx can inhibit S. pyogenes colonization through production of bacteriocins and competition for attachment sites

- S. pyogenes can displace normal flora through its own bacteriocin production and rapid growth in favorable conditions

Interactions with Staphylococcus aureus:

- Co-infection with S. aureus can occur in skin and soft tissue infections

- S. aureus can produce β-lactamases that can protect S. pyogenes from penicillin in mixed infections

- Antagonistic relationships have been observed where S. pyogenes inhibits S. aureus through streptococcin production

Viral-Bacterial Synergism:

- Preceding or concurrent viral infections (especially influenza and other respiratory viruses) can enhance S. pyogenes colonization and invasion

- Viral infections may damage epithelial barriers, expose receptors for bacterial adherence, and modulate host immune responses

- This synergism may explain seasonal patterns of streptococcal pharyngitis

Interactions with Respiratory Tract Microbiome:

- Changes in the composition of the respiratory microbiome may influence susceptibility to S. pyogenes colonization and infection

- Lactobacilli and other probiotic bacteria may inhibit S. pyogenes through production of organic acids and bacteriocins

Biofilm Formation:

- S. pyogenes can form biofilms alone or as part of polymicrobial communities

- Biofilm formation enhances antibiotic tolerance and resistance to host immune defenses

- In biofilms, S. pyogenes can exchange genetic material with other bacteria, potentially acquiring virulence or resistance determinants

These microbial interactions influence S. pyogenes colonization, persistence, and pathogenicity, and may explain some of the variability in clinical presentations and outcomes of S. pyogenes infections.

Research Significance

S. pyogenes serves as an important model organism for studying various aspects of bacterial pathogenesis and host-pathogen interactions:

Virulence Factor Regulation:

- S. pyogenes has sophisticated regulatory networks that control virulence gene expression in response to environmental cues

- Studies of these networks have provided insights into bacterial adaptation to different host niches

- The CovR/S (CsrR/S) two-component system is a paradigm for understanding how bacteria regulate virulence in response to environmental signals

Host-Pathogen Interactions:

- Research on S. pyogenes has elucidated mechanisms of bacterial adherence, invasion, and immune evasion

- Studies of M protein and other surface molecules have advanced understanding of bacterial molecular mimicry and autoimmunity

- Investigation of superantigens has provided insights into T-cell activation and systemic inflammatory responses

Post-Infectious Sequelae:

- Research on rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis has contributed to understanding of autoimmune and immune complex-mediated diseases

- These studies have broader implications for other post-infectious autoimmune conditions

Vaccine Development:

- Efforts to develop S. pyogenes vaccines have advanced understanding of protective immunity against extracellular pathogens

- Challenges in S. pyogenes vaccine development have stimulated innovative approaches to bacterial vaccine design

Antibiotic Resistance and Treatment:

- Despite low rates of β-lactam resistance, S. pyogenes has developed resistance to macrolides and other antibiotics

- Studies of resistance mechanisms contribute to broader understanding of bac (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)