Fusobacterium nucleatum

Key Characteristics

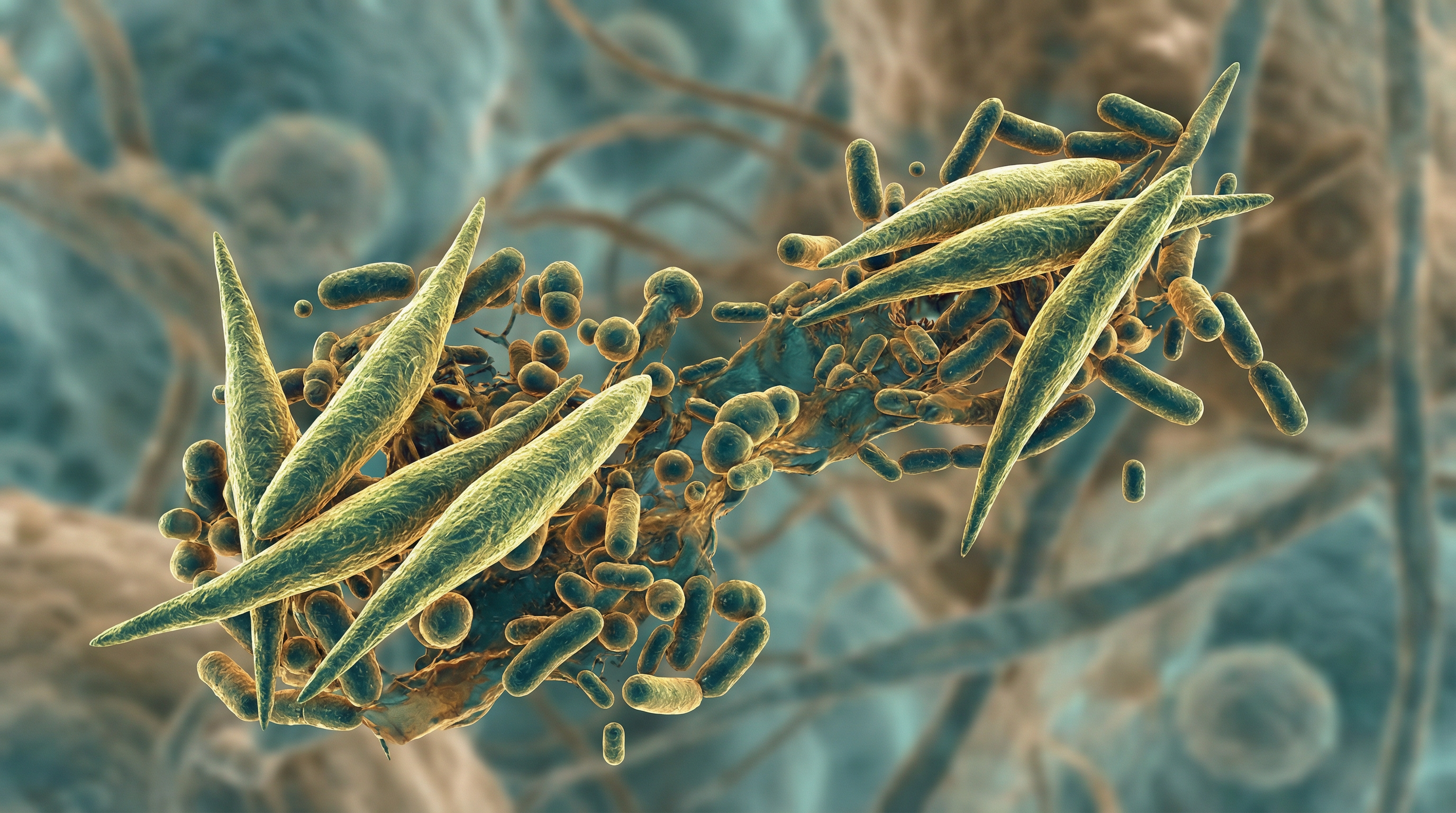

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a Gram-negative, obligate anaerobic, non-spore-forming, non-motile, spindle-shaped bacterium. It belongs to the Fusobacteriaceae family within the Fusobacteria phylum. The species includes several subspecies: nucleatum, polymorphum, vincentii, animalis, fusiforme, and canifelium.

F. nucleatum is primarily found in the oral cavity but can also colonize the urogenital tract, intestinal tract, and upper digestive system. It possesses numerous adhesins (Aid1, CmpA, Fap2, FomA, FadA, and RadD) that facilitate its ability to co-aggregate with other bacteria, invade host tissues, and spread throughout the body.

Role in Human Microbiome

F. nucleatum plays a significant role in the human microbiome, particularly in:

Oral cavity: It serves as a critical "bridge organism" in dental plaque formation, facilitating co-aggregation between early and late colonizers in biofilm development. It represents a key component of the oral microbiome and is commonly found in dental plaque.

Intestinal tract: While not a dominant member of the healthy gut microbiome, it can colonize the intestinal environment, particularly in disease states.

Microbial ecology: It functions as a co-aggregation factor with almost all bacterial species that participate in oral plaque formation, creating a complex microbial community.

Health Implications

Pathogenic Potential

F. nucleatum is associated with various pathological conditions:

Periodontal disease: It is a major contributor to periodontitis, where it participates in biofilm formation and triggers inflammatory responses.

Colorectal cancer (CRC): Substantial evidence links F. nucleatum to colorectal carcinogenesis. Its abundance in CRC tissue has been inversely correlated with overall survival.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): It is frequently detected in OSCC tissues at higher levels than in adjacent healthy mucosa.

Systemic infections: It can cause diverse infections including inflammatory bowel disease, angina, ulcerative colitis, persistent otitis, sinusitis, peritonsillar abscesses, brain abscesses, pulmonary abscesses, Crohn's disease, gynecological abscesses, neonatal sepsis, Lemierre's syndrome, and infective endocarditis.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes: It has been associated with preterm birth and other pregnancy complications.

Oncogenic Mechanisms

F. nucleatum contributes to carcinogenesis through sophisticated molecular mechanisms:

Subspecies-Specific Pathogenicity (Fna C2 Clade)[1][1]

A landmark 2024 Nature study identified that F. nucleatum subspecies animalis Clade 2 (Fna C2) specifically dominates the colorectal cancer niche:

- Found in ~50% of CRC tumors; 195 genetic differences from non-pathogenic clades

- Pathoadaptations: Evolved ethanolamine (eut) and 1,2-propanediol (pdu) metabolic operons

- Acid Resistance: Glutamate-dependent acid resistance (GDAR) system enables pH 3 survival

- Clinical Impact: GSSG/GSH ratio increased 3.5-fold (p=0.0031); intestinal adenomas significantly increased

Tumor Colonization via Fap2 Adhesin[2][3]

The 400 kDa Fap2 protein serves dual functions:

- Structure: 45-50 nm rod-shaped beta-helix with matchstick-like tip (2025 cryo-EM)[3][5]

- Tumor Binding: Galactose-specific lectin binds Gal-GalNAc oncofetal antigen overexpressed in adenocarcinomas

- Binding Data: 6.1-fold higher binding to adenocarcinoma vs normal tissue; Fap2-deficient mutants show 45.6-fold lower colonization

- Immune Evasion: Binds TIGIT on NK cells and T cells, triggering inhibitory signaling (KD ~0.6 μM)

FadA-Mediated Wnt/β-Catenin Activation[4][2]

- FadA binds E-cadherin using zipper mechanism

- Activates β-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway

- Promotes cell proliferation, oncogene expression (Myc, Cyclin D1), and tumor growth

Crypt Colonization and Stem Cell Activation[5][4]

2025 research revealed F. nucleatum colonizes the depths of gut crypts:

- Targets LY6A+ revival stem cells (RSCs)

- Upregulates ribosomal protein S14 (RPS14), driving hyperproliferation

- Genetic ablation of Ly6a or Rps14 significantly reduced tumor loads (P<0.001)

CbpF-CEACAM1 Immune Checkpoint Activation[6][6]

- CbpF is a trimeric autotransporter adhesin

- Binds CEACAM1 on T cells and NK cells with nanomolar affinity (KD 6.2 nM)

- Unique lateral loop D142-Y149 is novel CEACAM1 binding motif

- Enables rational drug design targeting F. nucleatum in CRC

Metabolic Activities

F. nucleatum exhibits several key metabolic activities:

Fermentation: As an anaerobic organism, it relies on fermentation for energy production.

Protein degradation: It can degrade various proteins, contributing to tissue destruction in periodontal disease.

Butyrate production: It produces butyrate as a metabolic end-product, which can influence host cell gene expression and immune responses.

Amino acid utilization: It can metabolize certain amino acids, particularly glutamate and aspartate.

Outer membrane vesicle production: It releases OMVs containing virulence factors and immunomodulatory molecules.

Clinical Relevance

F. nucleatum has significant clinical relevance across multiple areas:

Cancer Biomarker Potential[7][12]

Fecal Biomarker

- Meta-analysis (16 studies, 4,883 subjects): Sensitivity 70%, Specificity 79%, AUC 0.82

- Combined with FIT: Sensitivity increases from 73.1% to 92.3% (p<0.001)

- Diagnostic Odds Ratio: 9 (95% CI 7-11)

Salivary Biomarker[8][10]

- Detection Rate: 93.3% in saliva vs 76.7% in tumor tissue

- Diagnostic AUC: 0.841 (95% CI 0.797-0.879)

- Prognostic Value: Independent prognostic factor with OS HR 4.001, DFS HR 3.648

- Advantages: Noninvasive; superior to CEA and CA19-9 in seronegative patients

Prognostic Impact

- Overall Survival: High Fn load is independent prognostic factor for shorter OS and CSS

- Hazard Ratios: CRC-specific mortality HR 1.58 (Fn-high) vs Fn-negative[9][11]

- Gastric Cancer: Median survival 244.5 days (Fn+) vs 1229.5 days (Fn-), p=0.009

- Metastasis: Associated with lymph node involvement and distant metastasis

Treatment Resistance[10][7]

- Chemotherapy: Promotes 5-FU and oxaliplatin resistance via TLR4/MYD88-mediated autophagy

- Mechanism: Protective autophagy degrades chemotherapeutic agents; BIRC3 upregulation inhibits apoptosis

- Clinical Evidence: Targeting anaerobic bacteria with antibiotics pre-surgery reduced recurrence/death risk by 25.5%

Gum-Gut Axis and Ulcerative Colitis[11][9]

- Periodontitis increases UC risk 1.5-fold (aHR 1.56, 95% CI 1.13-2.15)

- F. nucleatum detected in 51.78% of UC intestinal tissues

- Induces ferroptosis in intestinal epithelial cells (GPX4 down, ACSL4 up)

- Ferrostatin-1 treatment increased survival from 62.5% to 85.7%

Therapeutic Strategies

- Metronidazole: Primary antibiotic for Fn; reduces fecal abundance

- Periodontal Treatment: Reduces Fn abundance in stools

- Phage Therapy: M13@Ag phage therapy targeting Fn in development

- Vaccines: FomA outer membrane protein as target

- Antimicrobial Peptides: Br-JI peptide shows efficacy against Fn-enriched tumors

Interaction with Other Microorganisms

F. nucleatum interacts extensively with other microorganisms:

Co-aggregation: It serves as a bridge between early colonizers (streptococci and actinomyces) and late colonizers (P. gingivalis) in dental plaque formation.

Synergistic pathogenicity: It can enhance the virulence of other pathogens, particularly in polymicrobial infections.

Biofilm formation: It contributes to the structural integrity and metabolic activities of oral biofilms.

Interspecies communication: It participates in quorum sensing and other forms of bacterial communication within microbial communities.

Dysbiosis promotion: Its presence can contribute to microbial imbalance in both oral and gut environments.

Research Significance

F. nucleatum has become a focus of significant research interest:

Cancer-microbiome connection: It represents one of the most well-documented links between specific bacteria and cancer development.

Oral-systemic health connection: It exemplifies how oral bacteria can influence systemic health conditions.

Biofilm dynamics: It serves as a model organism for understanding polymicrobial biofilm formation and function.

Therapeutic development: Research on its virulence mechanisms is informing the development of novel therapeutic approaches.

Diagnostic applications: Detection methods for F. nucleatum are being developed for early cancer screening and risk assessment.

Recent research has identified that a specific clade within F. nucleatum subspecies (Fna C2) predominates in the colorectal cancer niche, suggesting strain-specific effects in carcinogenesis. This highlights the importance of strain-level analysis in understanding the role of this bacterium in health and disease.

References

Pignatelli P, et al. The Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Oral and Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2358.

Nagy KN, et al. The microflora associated with human oral carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:304–308.

Keku TO, et al. The gastrointestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G351–G363.

Sears CL, et al. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:317–328.

Brennan CA, et al. Bacterial species selectively colonize the colorectal cancer microenvironment to promote tumor growth. Nature. 2024;627(8001):1022-1030.

Rubinstein MR, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:195–206.

Gur C, et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015;42:344–355.