Propionibacterium acnes

Overview

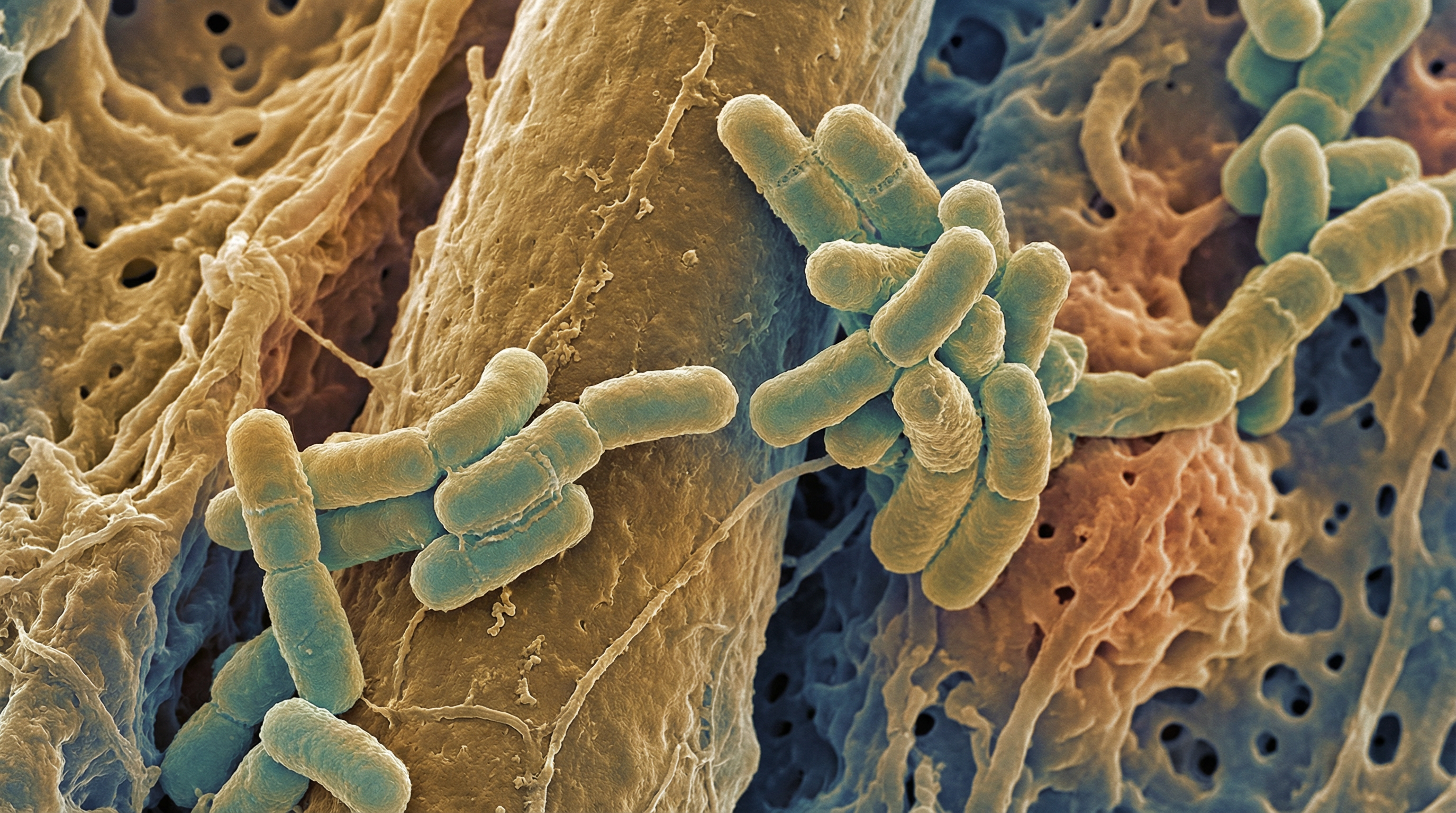

Propionibacterium acnes (recently reclassified as Cutibacterium acnes) is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that constitutes a major part of the human skin microbiome. It is the most abundant bacterium on human skin, particularly in sebaceous areas such as the face, scalp, chest, and back. P. acnes has a complex relationship with human health, functioning as both a commensal organism that helps maintain skin homeostasis and as an opportunistic pathogen associated with various conditions, most notably acne vulgaris. The bacterium has a clonal population structure comprising several distinct phylogenetic groups (types I, II, and III), with different strains exhibiting varying degrees of association with skin health or disease. P. acnes produces propionic acid as a metabolic byproduct (hence its genus name), along with other short-chain fatty acids that contribute to the acidic environment of the skin. Its ability to thrive in the lipid-rich, anaerobic environment of sebaceous follicles, coupled with its diverse metabolic capabilities and interactions with the host immune system, makes P. acnes a key player in skin ecology and a significant factor in both skin health and disease.

Characteristics

Propionibacterium acnes exhibits several distinctive characteristics that define its ecological niche and biological activities:

- Morphology: Rod-shaped (bacillus) bacterium, sometimes appearing slightly curved or pleomorphic, with a size of approximately 0.5-1.2 μm in width and 1-5 μm in length

- Cell wall structure: Gram-positive with a thick peptidoglycan layer

- Oxygen requirements: Facultative anaerobe, preferring low-oxygen environments but capable of surviving in the presence of oxygen

- Growth conditions: Optimal growth at 37°C and pH 6.0-7.0, typical of human skin conditions

- Motility: Non-motile

- Spore formation: Non-spore forming

- Genome features: Moderate-sized genome (approximately 2.5 Mb) with genes specialized for lipid metabolism and survival in the sebaceous environment

- Lipophilic nature: Adapted to thrive in lipid-rich environments, particularly the sebaceous follicles

- Biofilm formation: Capable of forming biofilms, enhancing its persistence and resistance to antimicrobial agents

- Colonial appearance: Forms small, round, white to beige colonies on appropriate anaerobic media

- Taxonomic classification: Recently reclassified from the genus Propionibacterium to Cutibacterium based on whole genome analysis and isolation source

- Phylogenetic diversity: Comprises several distinct phylogroups (types I, II, and III), with type I further divided into subtypes IA1, IA2, IB, and IC

P. acnes is particularly notable for its ability to metabolize sebum components, especially triglycerides, producing free fatty acids that contribute to the acidic mantle of the skin. Different phylogroups of P. acnes vary in their cellular morphology, aggregative properties, biochemical characteristics, inflammatory potential, and production of virulence factors, which may explain their differential associations with skin health and disease. Type IA1 strains, for example, are more frequently associated with acne vulgaris, while type II strains are more commonly found on healthy skin.

Role in Human Microbiome

Propionibacterium acnes occupies a significant niche within the human microbiome:

- Primary habitat: Predominantly found in sebaceous follicles and sebaceous gland-rich areas of the skin, including the face, scalp, chest, and back

- Secondary habitats: Also present in the oral cavity, external ear canal, conjunctiva, intestinal tract, and prostate

- Prevalence: Present in virtually all post-pubescent humans, constituting up to 90% of the microbiota in sebaceous areas

- Abundance: The most abundant bacterium on human skin, with population densities reaching 10^6 cells per square centimeter in sebum-rich regions

- Developmental trajectory: Increases dramatically during puberty when sebaceous glands become active, correlating with increased sebum production

- Ecological role: Functions as both a commensal organism and an opportunistic pathogen depending on strain type, host factors, and environmental conditions

- Microbiome network: Forms part of a complex microbial community on the skin, interacting with other residents such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Malassezia species

- Strain-specific distribution: Different phylogroups show distinct patterns of distribution, with some strains more associated with healthy skin and others with disease states

The ecological significance of P. acnes in the skin microbiome is multifaceted. As a commensal, it helps maintain skin health by producing short-chain fatty acids that contribute to the acidic pH of the skin, inhibiting the growth of pathogenic microorganisms. It also produces bacteriocins and thiopeptides that can suppress the growth of more harmful bacteria, effectively occupying ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by pathogens. However, under certain conditions—such as increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, or shifts in the composition of sebum—P. acnes can contribute to inflammatory processes, particularly in acne vulgaris. The balance between its beneficial and potentially harmful effects is influenced by factors including strain type, host genetics, immune response, and environmental conditions.

Health Implications

Propionibacterium acnes has diverse implications for human health, functioning as both a beneficial commensal and a potential pathogen:

Beneficial effects:

- Contributes to the acidic mantle of the skin through production of propionic acid and other short-chain fatty acids

- Produces antimicrobial substances that inhibit colonization by more pathogenic microorganisms

- May play a role in educating and modulating the skin immune system

- Some strains produce lipases that can break down sebum, potentially preventing follicular occlusion

Role in acne vulgaris:

- Contributes to acne pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms, though its exact role is complex

- Produces lipases that release free fatty acids from sebum triglycerides, potentially causing irritation

- Secretes porphyrins that can generate reactive oxygen species when exposed to light

- Triggers inflammatory responses through activation of toll-like receptors and production of proinflammatory cytokines

- Different strains have varying capacities to induce inflammation, with type IA1 strains most strongly associated with acne

Other skin conditions:

- Associated with progressive macular hypomelanosis, a condition characterized by hypopigmented macules

- May play a role in certain forms of folliculitis and other inflammatory skin conditions

- Implicated in some cases of rosacea, though its exact contribution remains unclear

Systemic infections:

- Can cause opportunistic infections, particularly in the context of implanted medical devices

- Associated with cases of endocarditis, particularly involving prosthetic heart valves

- Implicated in joint infections following orthopedic procedures

- Can cause infections of the central nervous system, especially following neurosurgical procedures

Other associations:

- Proposed links to conditions such as sarcoidosis, though causality remains controversial

- Potential associations with prostate inflammation and prostate cancer

- Implicated in some cases of SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis)

The health significance of P. acnes is highly context-dependent, influenced by factors including strain virulence, host susceptibility, and environmental conditions. Recent research has highlighted the importance of strain-level differences, with certain phylogroups showing stronger associations with disease while others appear more compatible with skin health. This understanding has led to a more nuanced view of P. acnes, moving away from considering it simply as a pathogen to recognizing its role as part of a complex ecosystem where the balance between different strains and other microorganisms contributes to either skin health or disease.

Metabolic Activities

Propionibacterium acnes exhibits specialized metabolic capabilities adapted to its primary habitat in the sebaceous follicles:

Lipid metabolism:

- Produces various lipases that hydrolyze triglycerides in sebum to release free fatty acids

- Metabolizes glycerol derived from triglyceride breakdown

- Can utilize sebum components as carbon and energy sources

- Generates propionic acid as a major end product of fermentation

Carbohydrate metabolism:

- Ferments glucose and other carbohydrates via the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway

- Utilizes the Wood-Werkman cycle (a modified version of the tricarboxylic acid cycle) for propionic acid production

- Produces short-chain fatty acids including propionic acid, acetic acid, and lactic acid

- Can metabolize a variety of sugars including glucose, fructose, and mannose

Protein and amino acid metabolism:

- Produces proteases that can degrade host proteins

- Utilizes certain amino acids as carbon and nitrogen sources

- Generates ammonia as a byproduct of amino acid catabolism

- Some strains produce tryptophanase, converting tryptophan to indole

Porphyrin production:

- Synthesizes coproporphyrin III and other porphyrins

- These porphyrins can act as photosensitizers, generating reactive oxygen species when exposed to light

- Porphyrin production varies among different strains and is influenced by environmental conditions

Biofilm formation:

- Produces extracellular polysaccharides and proteins that contribute to biofilm matrix

- Alters metabolic activities when growing in biofilms compared to planktonic state

- Exhibits increased resistance to antimicrobial agents in biofilm form

- Biofilm formation capabilities vary among different strains

Adaptation to skin environment:

- Tolerates the acidic pH of the skin surface

- Survives in low-oxygen environments within follicles

- Utilizes lipids as primary carbon sources in the sebum-rich environment

- Produces catalase and superoxide dismutase to cope with oxidative stress

The metabolic versatility of P. acnes allows it to thrive in the unique environment of the sebaceous follicle, where it can utilize the available lipids and adapt to the low-oxygen conditions. Its production of propionic acid and other short-chain fatty acids contributes to the acidic pH of the skin, which can inhibit the growth of other potentially pathogenic microorganisms. However, some of its metabolic activities, such as the production of lipases that release potentially irritating free fatty acids and the generation of porphyrins that can induce oxidative stress, may contribute to inflammatory processes in conditions like acne vulgaris. The metabolic capabilities also vary among different strains, which may partly explain the differential associations of certain phylogroups with skin health or disease.

Clinical Relevance

Propionibacterium acnes has significant clinical relevance across several domains:

Diagnostic considerations:

- Identification in clinical samples requires appropriate anaerobic culture techniques

- Extended incubation periods (up to 14 days) may be necessary for detection in some clinical specimens

- Molecular methods, including 16S rRNA sequencing and strain-specific PCR, can provide more rapid identification

- Strain typing (e.g., MLST, whole genome sequencing) may be relevant for distinguishing commensal from potentially pathogenic strains

- Contamination from skin must be considered when interpreting positive cultures

Treatment approaches:

- Targeted in acne vulgaris with topical and systemic antibiotics (e.g., clindamycin, erythromycin, tetracyclines)

- Increasing antibiotic resistance is a significant concern, with resistance rates exceeding 50% for some antibiotics in certain regions

- Benzoyl peroxide remains effective against P. acnes and does not induce resistance

- Isotretinoin reduces sebum production, indirectly affecting P. acnes populations

- Device-related and deep tissue infections often require prolonged antibiotic therapy and sometimes device removal

- Novel approaches include bacteriophage therapy, antimicrobial peptides, and strain-specific probiotics

Prevention strategies:

- Proper skin preparation before invasive procedures to reduce risk of implant-associated infections

- Prophylactic antibiotics for high-risk surgical procedures

- Maintenance of skin barrier function to support healthy microbiome balance

- Avoidance of unnecessary antibiotic use to prevent resistance development

- Development of anti-biofilm strategies for medical devices

Emerging therapeutic approaches:

- Microbiome-based therapies, including probiotics and prebiotics to promote beneficial strains

- Bacteriophages specifically targeting pathogenic P. acnes strains

- Antimicrobial peptides with selective activity against P. acnes

- Vaccine development targeting specific virulence factors

- Anti-inflammatory approaches addressing host response rather than bacterial elimination

Public health significance:

- Antibiotic resistance in P. acnes is a growing concern with implications for both acne treatment and management of serious infections

- Economic burden of acne vulgaris is substantial, affecting over 85% of adolescents and many adults

- Device-related infections contribute to healthcare costs and morbidity

- Understanding of strain-specific pathogenicity may lead to more targeted and effective interventions

The clinical approach to P. acnes has evolved from viewing it simply as a pathogen to be eliminated to recognizing its role as part of the normal skin microbiome, with only certain strains or contexts leading to pathology. This shift has important implications for treatment strategies, moving toward more selective approaches that target pathogenic strains or virulence factors while preserving beneficial components of the skin microbiome. The rising prevalence of antibiotic resistance in P. acnes also underscores the need for alternative therapeutic approaches and antimicrobial stewardship.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms

Propionibacterium acnes engages in complex interactions with other members of the skin microbiome:

Competitive relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

- Produces short-chain fatty acids that can be utilized by other microorganisms

- Contributes to the overall acidic environment of the skin, which supports the growth of acid-tolerant commensals

- Some strains may degrade complex substrates, making simpler compounds available to other microbes

Antagonistic relationships:

- Competes with other skin commensals for space and resources within the follicular environment

- Produces bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of other bacteria

- Occupies ecological niches that might otherwise be colonized by more pathogenic organisms

- Competition with Staphylococcus epidermidis for dominance in sebaceous follicles

Cooperative interactions:

- May engage in metabolic cross-feeding with other skin microbiota

**Antagonistic relatio (Content truncated due to size limit. Use line ranges to read in chunks)