Campylobacter jejuni

Overview

Campylobacter jejuni is the world's leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis, responsible for approximately 90% of campylobacteriosis cases[1]. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 estimated 135 million cases (95% CI: 106-175 million), 38,000 deaths (95% CI: 24,100-60,100), and 3.29 million disability-adjusted life years annually. Children under 5 years account for 48% of all deaths, with the highest incidence in Sub-Saharan Africa (2,730-3,090 per 100,000).

Characteristics

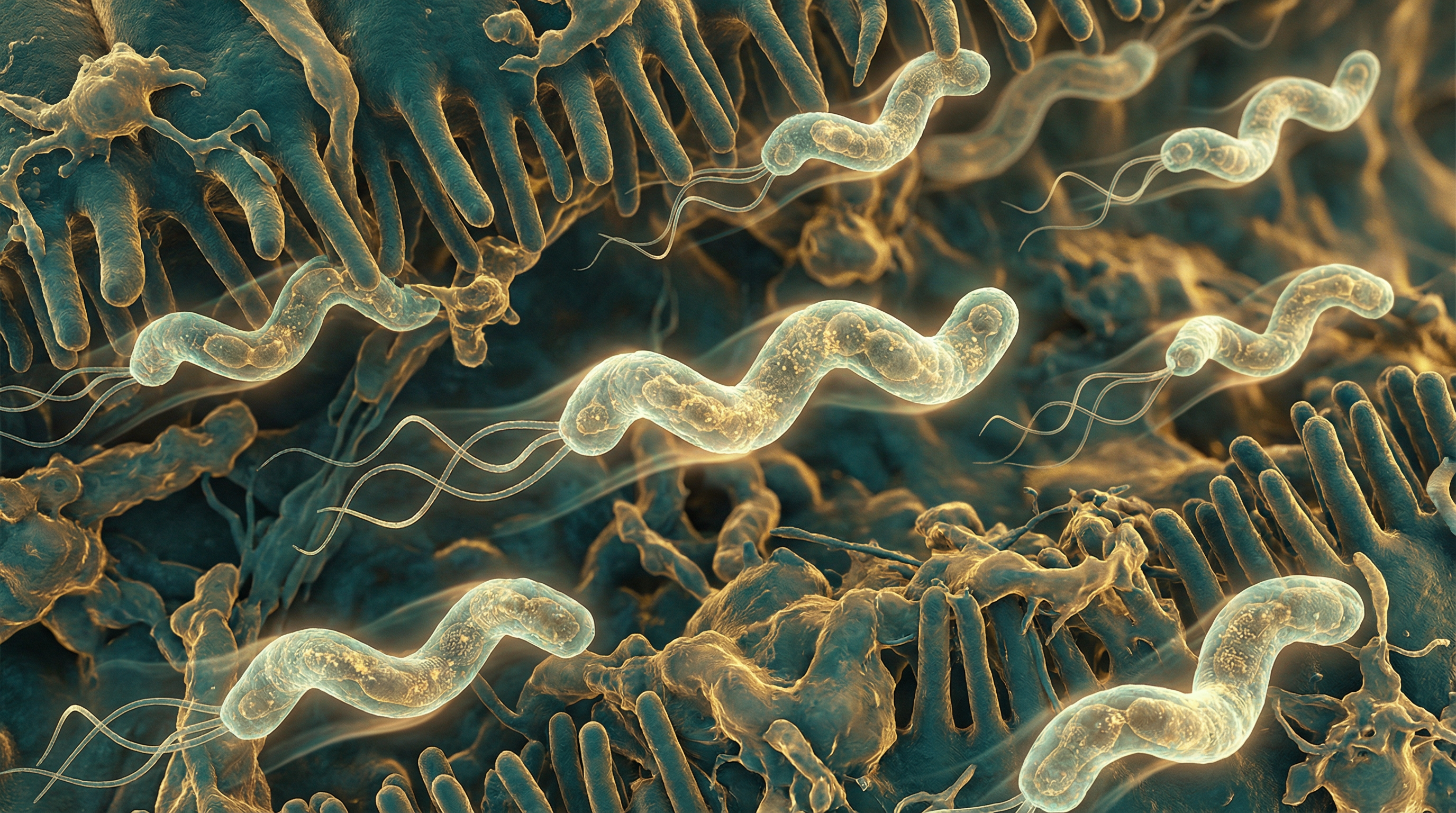

C. jejuni is a gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped bacterium with distinctive features:

- Motility: Highly motile via polar flagella (FlaA/FlaB) essential for colonization

- Growth requirements: Microaerophilic (3-5% O2), capnophilic; optimal growth at 42°C

- Metabolism: Asaccharolytic, relying on amino acids (L-serine, L-aspartate, L-glutamate) and Krebs cycle intermediates

- Infectious dose: Extremely low—as few as 50-800 organisms can cause infection

- Virulence genes: Nearly all strains carry cdtB (100%), cadF (100%), flgE2 (100%), iamA (99%), ciaB (87%)

Pathogenesis Mechanisms

Adhesion and Invasion

C. jejuni employs multiple adhesins to attach to and invade intestinal epithelial cells[2]:

- CadF: 37 kDa adhesin binding fibronectin; influences microfilament organization

- JlpA: Surface lipoprotein interacting with host HSP90α

- FlpA: Fibronectin-like protein required for maximal adherence

- Peb1: Periplasmic binding protein facilitating epithelial adhesion

Invasion occurs via a unique trigger mechanism:

- HtrA serine protease cleaves tight junction proteins (occludin, claudin-8, E-cadherin)

- Paracellular transmigration allows bacteria to reach the basolateral surface

- Subvasion: Invasion from below via Rac1 activation and focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation

- Flagellar Type III Secretion System (T3SS) delivers effectors (CiaB, CiaC, CiaD) promoting invasion

- Formation of Campylobacter-containing vacuole (CCV) that avoids lysosomal fusion

Cytolethal Distending Toxin (CDT)

CDT is a tripartite AB₂ genotoxin causing DNA damage and cell cycle arrest[3]:

| Subunit | Function |

|---|---|

| CdtA | Binding subunit; recognizes cholesterol-rich lipid rafts via CRAC-like motif |

| CdtB | Active enzymatic subunit with DNase I-like activity; causes DNA double-strand breaks |

| CdtC | Binding subunit; contains cholesterol recognition motif (LPFGYVQFTNPK) |

Mechanism of action:

- CdtA/CdtC bind to membrane cholesterol-rich microdomains

- Internalization via clathrin-dependent endocytosis

- CdtB retrograde trafficking through trans-Golgi to ER

- Nuclear translocation via nuclear localization signal

- DNA double-strand breaks → G2/M cell cycle arrest → cell distension/apoptosis

CDT also induces IL-8 production promoting leukocyte chemotaxis and activates NOD1/NOD2-dependent NF-κB signaling.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome Association

C. jejuni infection is the most common trigger of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), identified in 25-50% of cases[4].

Molecular Mimicry Mechanism

C. jejuni lipooligosaccharide (LOS) contains N-acetylneuraminic acid structures that mimic human peripheral nerve gangliosides:

| Ganglioside | Location | Associated GBS Variant | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM1 | Motor axonal membranes, nodes of Ranvier | AMAN | Anti-GM1 IgG |

| GD1a | Motor axonal membranes | AMAN/AMSAN | Anti-GD1a IgG |

| GQ1b | Cranial nerves | Miller Fisher syndrome | Anti-GQ1b IgG |

Pathogenic cascade:

- Infection triggers IgG1/IgG3 antibodies against LOS structures

- Cross-reactive antibodies bind peripheral nerve gangliosides

- Complement activation and membrane attack complex formation

- Macrophage recruitment to periaxonal space

- Disappearance of voltage-gated sodium channels

- Axonal degeneration or conduction block

Risk factors include:

- 77-100 fold increased GBS risk following C. jejuni infection

- Incidence: 0.07% of infections develop GBS (1 in 1,000)

- Onset: 10 days to 3 weeks after diarrhea

- LOS biosynthesis class A and B strains strongly correlated with AMAN

Antimicrobial Resistance

C. jejuni exhibits alarming and rising antimicrobial resistance, classified as a WHO high-priority pathogen[5].

Global Resistance Patterns

| Antibiotic | China | Iran | Jordan | US Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 83.5% | 67% | 46.6% | 24.5% → 29.7% |

| Tetracycline | 83.2% | 60% | 55.1% | - |

| Erythromycin | 0% (human) | 14% | 9.3% | Low |

| Gentamicin | - | 6% | 4.2% | Low |

Resistance mechanisms:

- Efflux pumps: cmeABC (74.7%), RE-cmeABC (71.3%)

- Target mutations: gyrA T86I (94.8% in resistant strains)

- Ribosomal protection: tet(O) in all tetracycline-resistant strains

- Multidrug resistance: 72.8% in China; 36.4% in Jordan

Poultry Reservoir and Food Safety

Poultry, especially chickens, are the primary reservoir and account for 50-80% of human cases[6].

Colonization Characteristics

- Commensal in chickens (no clinical disease)

- Colonization begins at 2-3 weeks of age

- Spreads to entire flock within days

- Levels: 10⁶-10¹⁰ CFU/g feces

- Up to 70% of European broiler batches colonized

Intervention Effectiveness

| Intervention | Reduction |

|---|---|

| Fly screens | Positive flocks: 51.4% → 15.4% |

| Bacteriophages (CP8, CP34) | 3.2 log₁₀ at slaughter |

| Probiotics (PoultryStar) | ≥6 log₁₀ CFU/g |

| Bacteriocins (OR-7) | >6 log₁₀ (million-fold) |

| Organic acids (formic acid + sorbate) | Complete elimination |

| 2% lactic acid on carcasses | 37-56% human risk reduction |

| Freezing (2-3 days) | 62-93% risk reduction |

Key finding: A 2 log₁₀ reduction on broiler carcasses equals a 30-fold decrease in human infection risk.

Post-Infectious Sequelae

Beyond acute gastroenteritis, C. jejuni causes significant chronic complications[7]:

| Sequela | Prevalence | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 4.48% | Unknown |

| Reactive arthritis | 1.72% | HLA-B27, male sex (3:1 ratio) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0.35% | IL23R/IL10 SNPs |

| Crohn's disease | 0.22% | Genetic susceptibility |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 0.07% | LOS class A/B strains |

Reactive arthritis typically presents within 2-4 weeks, affecting primarily knees and ankles, with duration of 3-12 months.

Microbiome Interactions

The intestinal microbiota provides crucial colonization resistance against C. jejuni[8]:

Protective Mechanisms

- Secondary bile acids: Deoxycholate (DCA) inhibits mTOR signaling and reduces colitis

- Clostridium XIVa: Enhances anti-inflammatory signaling; directs Treg expansion producing IL-10

- Bifidobacterium: Enriched in resistant hosts; biotransforms bile acids; downregulates flaA

- Lactobacillus: Inhibits growth via organic acid production and acidification

Colonization Factors

- Chemotaxis: CheA/CheY system navigates toward amino acids and favorable growth conditions

- Metabolic requirements: L-serine, L-aspartate, fumarate, pyruvate as primary substrates

- Iron acquisition: FeoB, Fur, CfrA, CfrB systems essential for colonization

- Phase variation: Capsular polysaccharide variation for host adaptation

Vaccine Development

No commercial vaccine exists, but multiple approaches show promise[9]:

Clinical Trials

- CJCV2 (NCT05500417): Phase 1 conjugate vaccine (capsule-CRM197 with ALFQ adjuvant); completed January 2025

- H2O2-inactivated vaccine: 83% protection in rhesus macaques (P=0.048); anti-flagellin titers of 92,042

Challenges

- Short 6-week broiler lifespan requires rapid immune response

- Antigenic diversity across strains and serotypes

- Safety concerns regarding ganglioside-mimicking structures

- Previous flagellin-based vaccines showed suboptimal clinical protection

One Health Approach

Effective C. jejuni control requires integrated surveillance across human, animal, and environmental sectors[10]:

Transmission Dynamics

- Poultry: Primary reservoir (50-80% attribution)

- Cattle: Secondary reservoir via raw milk and meat

- Wildlife: Amplifying hosts in anthropogenic landscapes

- Water: Surface water contamination facilitates transmission

- Climate change: Flooding and warming increase transmission risk

Surveillance Strategies

- Whole genome sequencing enables outbreak source identification

- Core genome MLST tracks clonal complexes across human-animal interface

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies provides comprehensive genomic analysis

- Multi-sectoral collaboration essential for effective control